From cherry blossoms in Japan to lavender fields in Provence, these are the flower-filled destinations travelers plan entire trips around — timing anxiety included.

Some trips are built around museums. Others around food, beaches or weather that doesn’t actively try to ruin your plans. And then there are flower trips — the kind that hinge on a narrow window of time, a bit of luck, and a willingness to plan an entire journey around something that might already be gone by the time you arrive.

Flower-based travel is part pilgrimage, part gamble. Show up too early and you’re staring at bare branches or tightly closed buds. Show up too late and the petals are already carpeting the ground, beautiful in their own way but not quite what you came for. That anxiety — the constant checking of bloom forecasts, the obsessive refreshing of social feeds — is part of the appeal.

Around the world, certain flowers have become inseparable from the places that grow them. They shape city identities, define seasons and quietly drive tourism in ways that feel emotional rather than transactional.

From fleeting cherry blossoms in Japan to marigolds that transform Mexico during Day of the Dead, these are the most popular flower-based destinations around the world — and why travelers keep chasing something so beautifully temporary.

Cherry Blossoms in Japan

If flower-based travel has a gold standard, this is it.

Cherry blossom season in Japan isn’t just something you stumble into while sightseeing — it’s something people plan years around. Flights are booked with fingers crossed. Hotels fill months in advance. Entire itineraries hinge on a few fragile days when sakura trees briefly do what they’ve always done, indifferent to human schedules.

In cities like Tokyo and Kyoto, cherry blossoms turn everyday spaces into temporary landmarks. Parks, riverbanks and neighborhood streets become gathering places where people picnic under clouds of pink and white petals, fully aware that the moment is already slipping away.

But Japan’s cherry blossom appeal isn’t limited to the obvious places. Many travelers deliberately skip the most crowded spots, chasing blooms in lesser-known cities or quieter regions where the experience feels more personal, less performative. The flowers are the same; the atmosphere changes completely.

What makes cherry blossoms such a powerful travel draw is their refusal to cooperate. Bloom forecasts are studied obsessively, but weather still wins. A warm spell can speed things up. A cold snap can delay everything. Miss the window by a week, and the trees are already shedding, their petals collecting on sidewalks and water like a beautiful consolation prize.

That uncertainty is exactly the point. Cherry blossom season taps into something deeper than scenery — it’s about impermanence, attention and showing up when it matters. The flowers don’t last, and that’s why people keep coming back, hoping to catch them at just the right moment next time.

When to go:

Late March through early April, though bloom timing varies by region and year. Southern areas tend to flower earlier; northern regions follow later.

Traveler tips:

Book accommodations well in advance and stay flexible if possible. Consider smaller cities or less-famous parks for a quieter experience, and don’t panic if petals start falling — peak bloom is beautiful, but so is the moment just after.

If autumn leaves are more your thing, try timing a trip with koyo in Japan.

Tulips in the Netherlands

Tulips in the Netherlands occupy a strange space between nature and choreography.

For a few weeks each spring, the countryside turns into a living color chart. Red, yellow, pink and purple fields stretch toward the horizon with a precision that feels faintly suspicious, as if someone went out overnight with a ruler and a vision board. Which, historically speaking, isn’t far off. Tulips here thrive under planning, patience and a national fondness for order.

Keukenhof gets most of the attention, and for good reason. Its displays feel almost theatrical — rows of blooms arranged with such care they verge on surreal. Yet the real magic happens once you leave the gates behind. Beyond the gardens, tulip fields take over entire regions, lining rural roads and canals in broad, unapologetic stripes. This is the version best experienced slowly, preferably by bike, with plenty of stops just to stare.

Tulips have been woven into Dutch identity for centuries, from economic obsession to cultural shorthand. They appear everywhere — souvenirs, postcards, tourism campaigns — standing in for the country itself.

Timing remains the only wildcard. Tulip season moves quickly and without apology. Arrive too early and the fields sit quietly green. Arrive too late and the flowers have already been cut back, their work complete. The reward goes to travelers willing to plan carefully and accept that the window stays narrow for a reason.

When to go:

Mid-March through early May, with peak blooms usually landing in April. Weather determines everything.

Traveler tips:

Keukenhof earns its reputation, but the countryside delivers the scale. Rent a bike or explore towns near Lisse to see the fields up close. Early mornings and overcast days often bring richer colors and fewer crowds.

EXPLORE MORE: A Benelux Itinerary

Lavender in Provence, France

For a brief stretch of summer, the landscape in Provence shifts into something almost unreal. Hills roll out in soft purples and silvers, neat rows of lavender stretching toward stone farmhouses and distant mountains. The scent hangs in the air, impossible to ignore, turning even a simple drive into a sensory experience.

Unlike flowers that cluster in parks or gardens, lavender defines the countryside itself. It’s woven into the region’s identity. Villages, roads and fields all participate, making Provence feel temporarily transformed rather than decorated.

Timing is everything. Lavender season is short and unforgiving. Arrive too early and the fields are still green, quietly preparing. Arrive too late and the harvest has already begun, leaving behind trimmed stems and a faint echo of what was there just days before. Travelers plan entire itineraries around this window, knowing the payoff lasts only weeks.

What draws people back year after year is the completeness of the experience. Lavender isn’t just pretty — it’s something you smell, feel and remember. The color, the heat of summer, the hum of bees in the fields — together they create a moment that feels both abundant and fleeting.

When to go:

Late June through mid-July is peak lavender season, though timing varies slightly by elevation and location

Traveler tips:

Base yourself near smaller villages rather than major cities to be closer to the fields. Early morning and late afternoon offer softer light and fewer crowds. Check local harvest updates before finalizing dates — once cutting starts, the show’s over fast.

Bluebells and Cottage Gardens in the United Kingdom

Spring in the UK arrives softly. One day the woods look ordinary. The next, they’re flooded with blue. Bluebells carpet forests and parklands in dense, low waves, transforming familiar paths into something quietly otherworldly, the sort of setting that has inspired centuries of fairy lore. People travel specifically to see them — often returning to the same woods year after year, guarding favorite spots like secrets.

Bluebell season carries real weight here. These flowers signal renewal, nostalgia, and a very specific version of spring that feels deeply tied to place. Walk through ancient woodland at peak bloom and the effect feels almost hushed, as if the landscape expects visitors to lower their voices.

Beyond the woods, flowers define the UK in more cultivated ways. Cottage gardens explode with color as soon as the weather allows, packed with foxgloves, roses, delphiniums and whatever survived winter. Places like the Cotswolds and Cornwall, along with other parts of the English countryside, draw travelers who time their visits around bloom cycles rather than attractions.

Timing remains everything. Bluebells bloom for a narrow window, usually April into early May, and weather decides the exact moment. Miss it and the woods return to green without ceremony. Catch it right and the experience lingers far longer than the walk itself.

For travelers who leave before the season peaks — or who miss it entirely — flowers still carry meaning back home. Many people turn to flower delivery UK services as a way to stay connected to the landscapes they traveled for, even after the blooms fade from view.

When to go:

April through May for bluebells; late spring through early summer for cottage gardens

Traveler tips:

Stick to marked paths in bluebell woods — trampling damages bulbs that take years to recover. Visit early in the morning or on weekdays for a quieter experience, and expect weather to shift plans without warning.

EAT UP: Guide to British Cuisine

Roses in Portland, Oregon, USA

Not all flower destinations are rural or seasonal escapes. Some are baked directly into a city’s identity.

Portland has been calling itself the City of Roses for more than a century, and unlike many nicknames, this one still holds up. Roses aren’t tucked away on the outskirts or limited to a single bloom window — they’re part of the city’s fabric, climbing fences, lining streets and anchoring public spaces.

The International Rose Test Garden is the obvious centerpiece, perched above the city with views that stretch toward Mount Hood on clear days. Thousands of varieties bloom here each year, carefully tended and quietly competitive, as growers test new roses destined for gardens around the world. It’s formal, yes, but never stuffy. People wander, linger, and treat it less like an attraction and more like a shared backyard.

Timing still matters, but the window is generous. Roses bloom over months rather than days, offering a softer version of flower travel — less gamble, more assurance. It’s a reminder that not every floral pilgrimage has to come with anxiety attached.

When to go:

Late May through September, with peak blooms typically in June and July

Traveler tips:

Visit the rose garden early in the morning or on weekdays for quieter paths. Pair your visit with a walk through nearby Washington Park or a slow neighborhood stroll to see how roses show up beyond the formal garden.

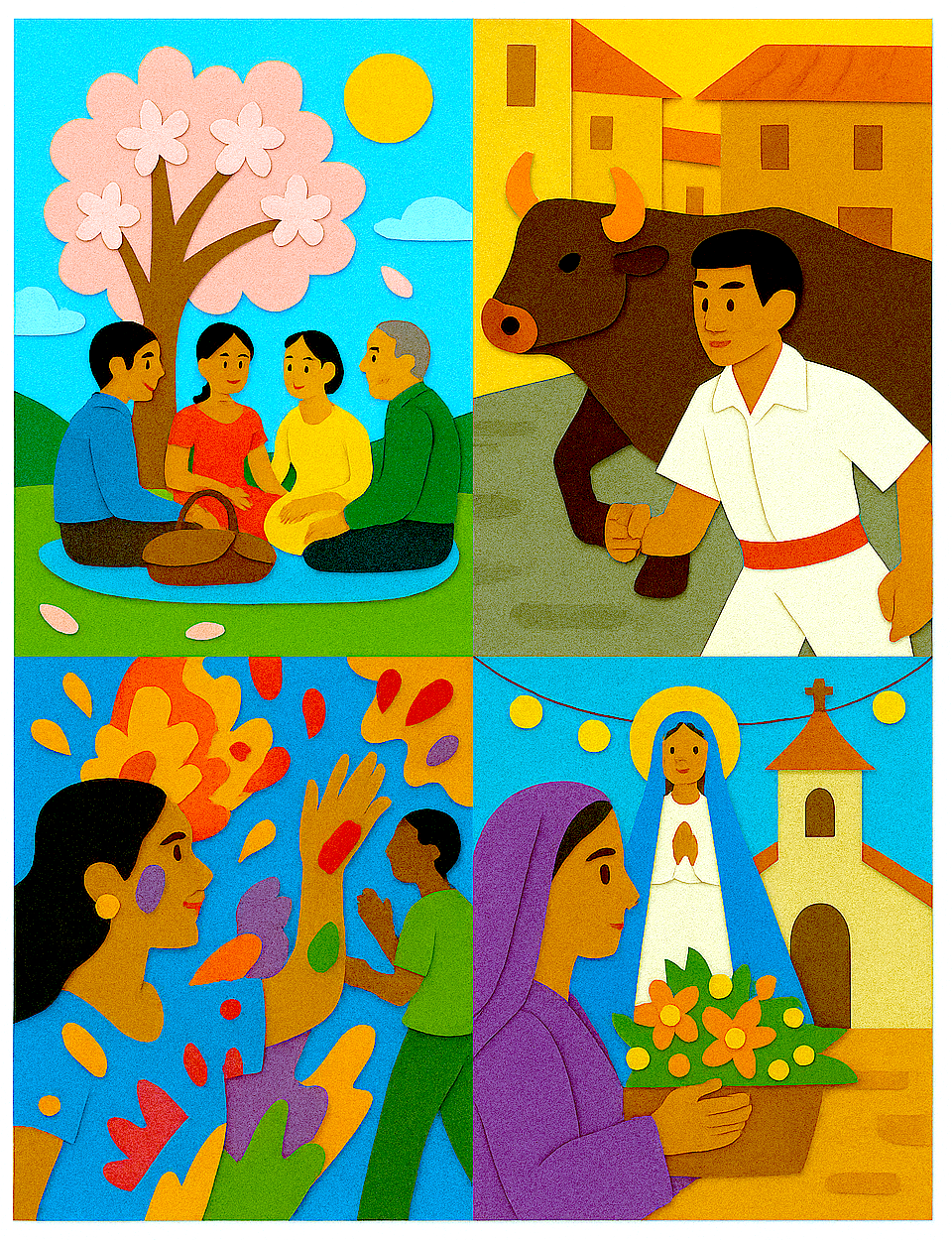

Marigolds in Mexico

Marigolds in Mexico arrive in saturated waves of orange and gold, thick with scent and impossible to ignore. For a short stretch each fall, they flood streets, cemeteries, markets and kitchens, turning everyday places into something charged and ceremonial.

During Día de los Muertos, marigolds have a job description. Their color and smell guide spirits back home, tracing paths from doorways to altars to graves. You see them scattered like breadcrumbs, piled high around photographs and candles, woven into arches and crowns. Cemeteries like the Panteón 5 de Diciembre in Puerto Vallarta glow after dark, petals catching candlelight while families linger, talk, eat and remember.

Markets feel especially alive during this time. Buckets overflow with marigolds sold by the armful, meant for someone specific rather than general display. These flowers serve memory, grief, humor and affection all at once. The mood holds warmth alongside loss, celebration alongside reverence.

Timing matters intensely. Arrive outside the window, and the marigolds retreat just as quickly as they appeared, taking the altars and processions with them. During Día de los Muertos, entire cities feel temporarily reshaped, as if normal life stepped aside to make room for something older and more intimate.

Travelers return because the experience feels human at its core. Marigolds turn flowers into language — one spoken between generations, across time and through ritual. You leave with the sense that beauty here carries responsibility.

When to go:

Late October through November 2, with celebrations peaking around Día de los Muertos.

Traveler tips:

Move slowly and observe before engaging. Markets offer the fullest sensory experience early in the day, while cemeteries come alive after sunset. Smaller towns often provide deeper, more personal encounters than major cities.

DO YOU BELIEVE IN MAGIC? Samhain Divination Spells

Orchids in Singapore

Orchids in Singapore look like something engineered in a lab by someone with a flair for drama. They curl, twist, spike and glow in colors that feel almost synthetic. Some resemble insects. Others look mid-metamorphosis. It’s easy to forget these things grow out of soil. In Singapore, orchids feel closer to science fiction than gardening — which explains why the city embraced them so completely.

Walk through the Singapore Botanic Gardens and the orchid collection feels less like a stroll and more like a catalog of botanical overachievement. Thousands of varieties bloom with unapologetic confidence, each labeled and tracked, as if daring you to question how much control humans can exert over nature. Singapore answers that question decisively.

Gardens by the Bay doubles down on the spectacle. Orchids glow beneath glass domes, backlit and theatrical, performing for visitors who came expecting futuristic architecture and left thinking about flowers instead. It’s maximalist. It’s bizarrely beautiful. It works.

To locals, orchids signal status and ambition. Hybrid blooms get named after visiting dignitaries and world leaders, turning flowers into diplomatic souvenirs. Giving someone an orchid here carries weight. These plants represent polish, progress, and a country very comfortable presenting itself as hyper-competent.

For travelers, orchids offer a rare luxury: certainty. They bloom year-round, immune to weather roulette. Singapore delivers the flowers exactly as promised — strange yet immaculate.

When to go:

Any time. Orchids thrive here year-round.

Traveler tips:

Start at the Singapore Botanic Gardens to see the sheer range, then head to Gardens by the Bay for spectacle. Pay attention to the shapes — orchids here reward close inspection and a slightly unhinged imagination.

SINGAPORE DAY TRIP: Visit Batam

Sunflowers in Tuscany, Italy

Sunflowers in Tuscany feel almost aggressive in their cheer. They line roads and hillsides in tight formation, huge yellow faces tracking the sun with unnerving enthusiasm. Driving through the countryside during peak bloom turns into a constant exercise in restraint — every few minutes presents another “pull over immediately” moment. Eventually, everyone gives in.

Sunflowers come with scale. Fields stretch wide and loud, unapologetically bright against dusty roads, cypress trees and stone farmhouses. In Italy, flowers have always carried deeper meaning, from religious devotion to seasonal rites of passage, a theme explored in Italian floristry and floral symbolism. The effect feels cinematic, the kind of scenery that convinces people their vacation photos finally match the fantasy.

Sunflowers also fit Tuscany’s rhythm. These fields appear alongside vineyards and wheat, part of a working landscape rather than a curated display. Locals treat them as another seasonal marker, a sign summer has arrived in earnest.

Timing still calls the shots. Sunflowers bloom quickly and fade just as fast, their faces drooping once the season turns. Catch them at their peak and the countryside feels electric. Miss it and the fields move on without ceremony.

People keep chasing sunflower season because it delivers instant joy. The experience carries zero mystery and full commitment: bold color, warm air, wide-open space. Sometimes that’s exactly what a trip needs.

When to go:

Late June through July, with timing varying slightly, depending on location and weather.

Traveler tips:

Rent a car to explore rural roads freely and expect frequent stops. Early morning and golden hour offer the best light and fewer crowds. Respect private property — the best views often come from the roadside.

Wildflowers in the Atacama Desert, Chile

Wildflowers in Chile’s Atacama Desert feel like a practical joke pulled by nature.

Most of the year, the Atacama ranks among the driest places on Earth — a landscape of dust, rock and silence that stretches toward the horizon with zero interest in pleasing visitors. Then, every so often, rain falls. Real rain. Enough to wake seeds that have been waiting patiently underground for years.

When that happens, the desert blooms.

Pink, purple, yellow and white flowers spread across the sand in an event locals call desierto florido. Hillsides and plains erupt into color where travelers expected emptiness. The transformation feels surreal.

This bloom carries real meaning in northern Chile. Locals treat it as a rare gift rather than a guarantee, a reminder that even the harshest landscapes hold quiet potential. People drive long distances to see it, fully aware the window stays brief and unpredictable.

Timing here plays hardball. Blooms depend entirely on rainfall, which varies wildly from year to year. Some years pass with nothing. Other years deliver an explosion that lasts weeks. Visitors arrive hopeful, checking forecasts and local reports, aware that certainty holds no power in this part of the world.

Travelers chase the Atacama bloom because it offers bragging rights and wonder in equal measure. Seeing flowers rise out of a desert famous for refusing life feels like witnessing a secret. Miss it, and the desert returns to its usual self without apology.

When to go:

August through October, only in years with sufficient rainfall. Exact timing changes annually.

Traveler tips:

Follow local Chilean news and park updates closely before planning. Stay flexible with travel dates if possible. Respect protected areas and resist the urge to wander into fragile bloom zones — this spectacle survives best when admired from a distance.

Lotus Flowers in Thailand and Vietnam

Lotus flowers thrive in places that feel calm on the surface and complicated underneath. You see them floating in temple ponds, rising clean and deliberate from murky water, petals intact and serene. In Thailand and Vietnam, lotus flowers carry centuries of meaning — purity, renewal, spiritual discipline — yet they remain deeply ordinary. People buy them on the way to pray. Vendors stack them beside fruit and incense. They exist as part of the daily rhythm rather than a special occasion.

At temples, lotus ponds shape the atmosphere. The flowers soften heat and noise, creating spaces that invite pause. Monks carry lotus buds during ceremonies. Worshippers offer them quietly, often without explanation.

Lotus flowers also appear far from sacred spaces. They grow in agricultural wetlands, in canals and along roads leading out of cities. In Vietnam, lotus seeds and roots end up in kitchens as often as altars. The flower bridges spiritual and practical life with ease.

Timing matters less here. Lotus season stretches generously across warmer months, and blooms appear daily, opening in the morning and closing by afternoon.

People remember lotus flowers because they anchor a sense of place. The experience feels quiet, grounded and human — a reminder that beauty can exist alongside routine.

When to go:

May through October, with peak blooms during the warmer, wetter months.

Traveler tips:

Visit temples early in the morning when lotus flowers open and crowds are thinner. Watch how locals interact with them before reaching for a camera. In Vietnam, try lotus tea or dishes using lotus root to experience the flower beyond the visual.

Why Flowers Keep Turning Places Into Destinations

Flower-based travel asks for patience, flexibility and a willingness to miss things. Entire trips hinge on weather patterns, bloom forecasts and timing that refuses to cooperate. And yet people keep coming back for more.

Maybe that’s the point.

Flowers force travelers to surrender control. You plan carefully, arrive hopeful, and accept whatever version of the moment shows up. Sometimes the fields explode with color. Sometimes petals carpet the ground, already slipping into memory. Either way, the experience lands because it belongs to that place, at that moment, and never quite repeats itself.

Across the world, flowers shape how places see themselves and how visitors remember them — from cherry blossoms signaling impermanence in Japan to marigolds guiding memory in Mexico, from meticulously cultivated orchids in Singapore to sunflowers lighting up Tuscan backroads. These destinations stay popular because they offer something temporary, visceral and stubbornly uncommodified.

You can photograph flowers, plan around them, even chase them across continents. You just can’t make them wait for you. And that tension — between preparation and surrender — is what keeps flower travel irresistible. –Wally

’TIS THE SEASON: Spring Festivals Around the World