From floating gardens to skull racks and chocolate money, Mesoamerican civilizations like the Aztec, Maya and Olmec were rewriting the rules of society — often with obsidian blades.

Imagine a world where chocolate is money, cities align perfectly with the stars, and rituals involve hearts ripped from chests to keep the sun from falling out of the sky.

Welcome to Mesoamerica, where civilizations like the Maya and Aztecs shaped the Americas while rewriting the rules of what it means to build and believe — with a whole lot of human sacrifice thrown in.

“With a swift motion, the heart is ripped from the chest, still beating, and offered to the heavens.”

While Europe was still playing with iron and forgetting how to write, Mesoamerican civilizations were busy creating some of the most awe-inspiring — and downright shocking — traditions and innovations the world has ever seen.

What Was Mesoamerica?

Mesoamerica is actually more of a concept than anything. It refers to the region and cultures that flourished in what is now Mexico and parts of Central America before the Spanish arrived. This includes legendary civilizations like the Olmec (the OGs), Maya (astronomers extraordinaire), and Aztec (master builders and blood-offerers).

Think of Mesoamerica as a sort of Silicon Valley of the ancient world — where everyone was innovating, connecting and competing to outdo each other in art, agriculture and, sometimes, human sacrifice.

With that in mind, let’s dive into the 20 most shocking facts about early Mexican cultures.

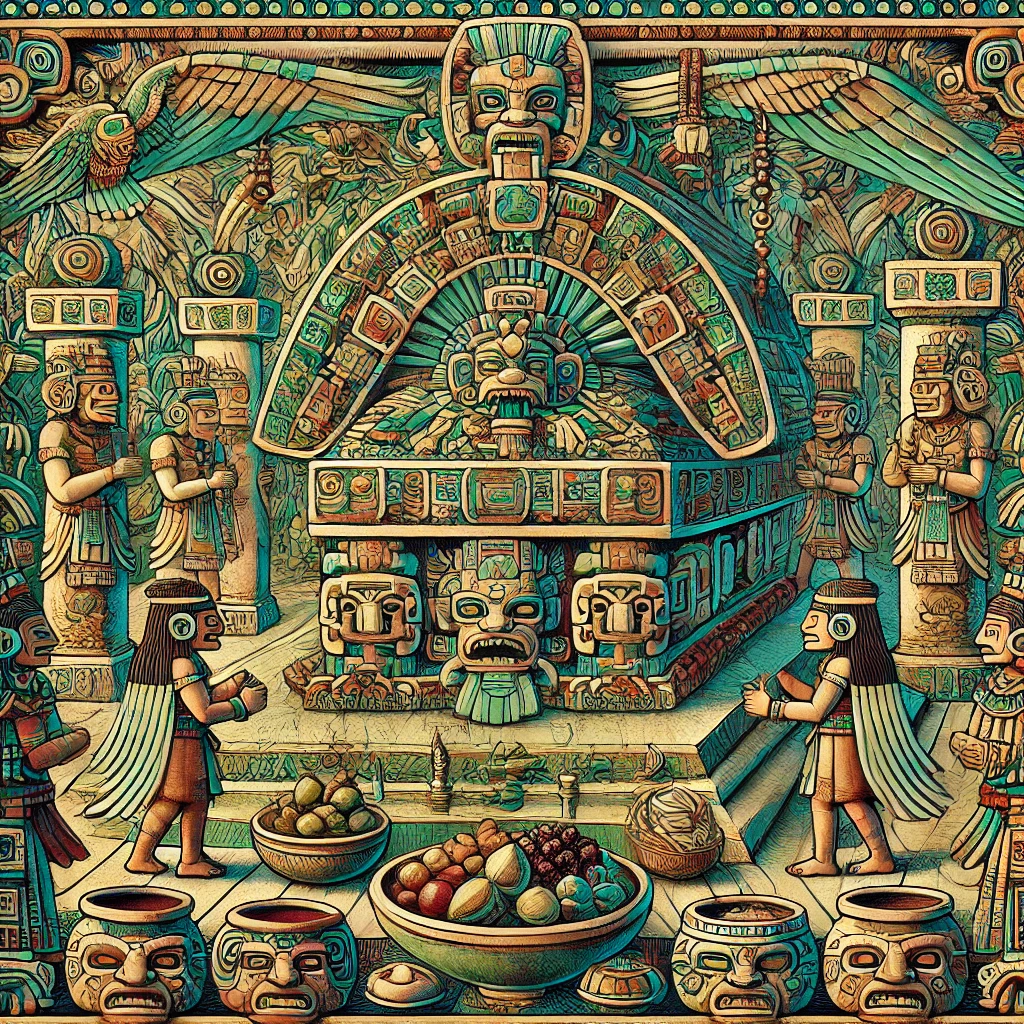

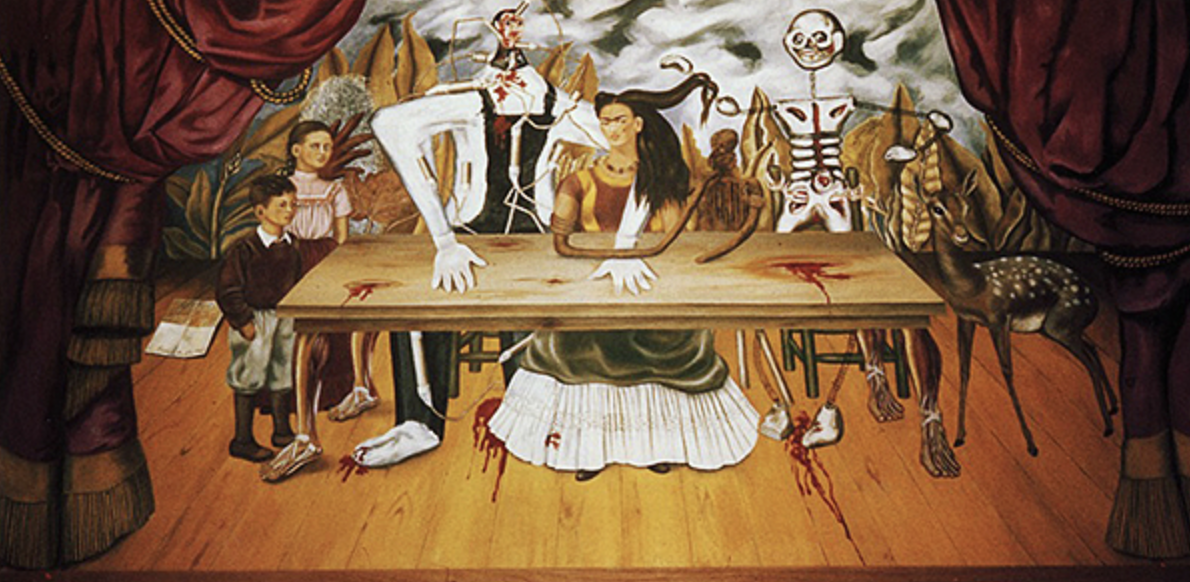

1. Human Sacrifice: The Price of the Sunrise

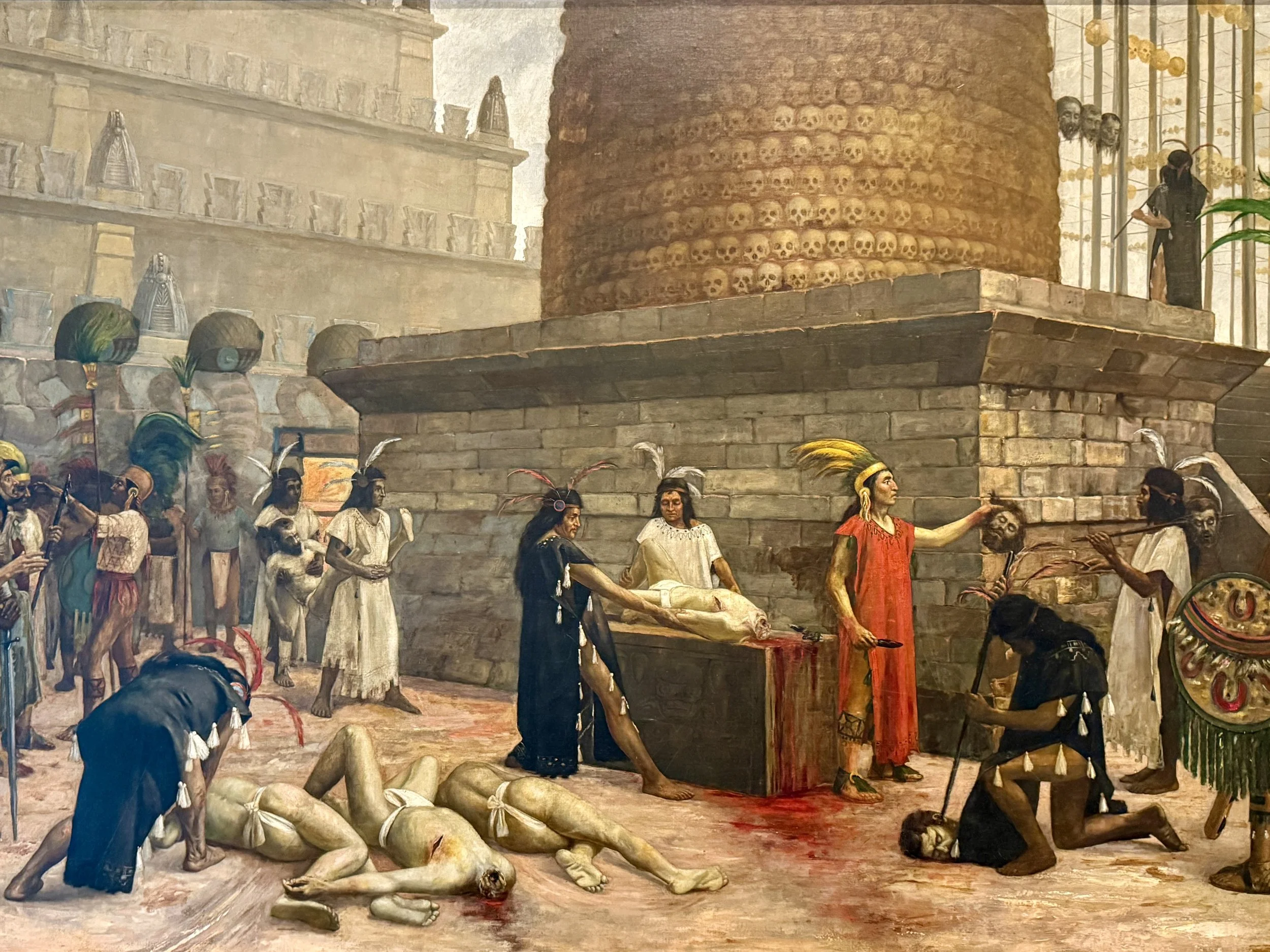

Worshippers would stand at the base of the towering Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, the heart of the Aztec empire. The air is thick with incense, the chants of priests echo across the plaza, and thousands of onlookers gather, awaiting the most sacred act of devotion. At the apex of the temple, a victim lies on a stone altar, surrounded by priests in jaguar and eagle costumes. The sun climbs higher in the sky as the priest raises an obsidian blade. With a swift motion, the heart is ripped from the chest, still beating, and offered to the heavens.

To the Aztecs, human sacrifice was a brutal necessity. They believed the gods had sacrificed themselves to create the world, and in return, humanity owed a debt of blood. One of the major Aztec gods, Huitzilopochtli, the sun deity and patron of warriors, required nourishment to continue his battle against darkness. Without regular sacrifices, the sun would stop rising, plunging the world into chaos. In one particularly shocking event, at the consecration of the Templo Mayor in 1487, it’s said that 20,000 people were sacrificed over four days.

This practice wasn’t isolated to the Aztecs, though. Other Mesoamerican cultures, like the Maya, also performed human sacrifice, albeit on a smaller scale. While horrifying by modern standards, this ritual was deeply spiritual and tied to the very fabric of their worldview: a cosmos fueled by cycles of life, death and renewal. For the Aztecs, each drop of blood spilled was a gift to keep the universe alive.

2. Cannibalism: A Taste of Divinity

At a royal feast in the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, among the tamales, chili-spiced sauces and cups of frothy chocolate, there might also have been something far more unsettling: human flesh. Reserved for priests, rulers and warriors, the consumption of sacrificial victims wasn’t a matter of hunger but of holiness. The Aztecs believed that by eating the flesh of those offered to the gods, they could absorb divine energy, making themselves closer to the deities they worshipped.

Cannibalism in Mesoamerican cultures is one of the most debated and misunderstood aspects of their society. Archaeological evidence and Spanish accounts suggest that the practice, while rare, was tied to specific rituals. For example, in ceremonies honoring the god Xipe Totec, victims were flayed, and their flesh was symbolically eaten to embody regeneration and agricultural fertility. While early Spanish chroniclers exaggerated the extent of cannibalism to demonize indigenous cultures, the underlying spiritual rationale was entirely alien to European sensibilities.

3. Tzompantli Skull Racks: Death on Display

In the bustling city of Tenochtitlan, visitors couldn’t miss the tzompantli. These towering racks, studded with human skulls, lined temple courtyards like grim trophies. For the Aztecs, the tzompantli was both an offering to the gods and a message to outsiders: This was a society willing to go to unimaginable lengths for their beliefs. Spaniards who arrived in the 16th century were shocked by the sight, their writings painting vivid pictures of thousands of skulls, bleached white by the sun, staring back at them.

But the tzompantli wasn’t just about intimidation. The Aztecs saw the skull as a sacred vessel of life’s essence, a way to honor the sacrifice made by those who gave their lives for the gods. Recent archaeological excavations in modern-day Mexico City uncovered one such skull rack, confirming its immense size and intricate construction. Researchers found skulls arranged with holes drilled through them, strung together like beads on a macabre necklace.

4. Bloodletting: Cutting Close to the Cosmos

The sharp sting of an obsidian blade, the drip of crimson onto sacred ground — this was devotion in Maya and Aztec culture.

While human sacrifice grabbed the headlines (and the hearts), bloodletting was far more common and deeply personal. Priests, rulers and even commoners pierced tongues, earlobes or limbs — sometimes with stingray spines — to feed the gods their own life force. During festivals, entire communities might bleed in unison, hoping to secure a good harvest or protection from catastrophe.

Why would anyone willingly endure such pain? For Mesoamericans, blood was the most sacred substance, a direct connection to the gods. By offering their own blood, they reaffirmed their role as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal.

5. Ritual Dismemberment: Offering to Many Gods

The calm after a sacrifice was often short-lived. In certain ceremonies, the Aztecs didn’t stop at removing the heart; they dismembered the victim’s body. Priests would scatter the parts across different temples and altars, each piece an offering to a specific god. A hand might be given to Xochipilli, the god of art and pleasure, while a head would go to Huitzilopochtli, the sun god.

To the Aztecs, this was cosmic bookkeeping. Each god had unique responsibilities, from rain to war, and each needed their share of devotion to keep the world functioning. Archaeological digs have uncovered evidence of these practices, with bones showing deliberate markings consistent with ritual dismemberment. Some temples even had distinct areas for specific body parts, suggesting an organized system for distributing offerings.

To the Aztec, these offerings were acts of love, ensuring the gods’ goodwill and the world’s continued existence.

6. Ollamaliztli: The Ballgame With Fatal Stakes

The ball bounces against a stone hoop, echoing across the court. Two teams of players, drenched in sweat, leap and twist, desperate to keep the rubber ball in play. The stakes couldn’t be higher: Losing could mean death.

The Mesoamerican ballgame, ollamaliztli, played by cultures like the Maya and Aztecs, was more than a game; it was a ritual symbolizing the eternal battle between life and death. Ollamaliztli was often played to honor gods or mark significant events, such as a military victory. While not all games ended in sacrifice, some did — especially during rituals. Archaeologists have found ball courts with murals depicting bound captives, suggesting that losing teams or their captains were sometimes offered as sacrifices.

The game itself was no small feat. The ball, made of solid rubber, could weigh up to 10 pounds, and players couldn’t use their hands or feet to touch it — only their hips, shoulders or thighs. Injuries were common, and the pressure of knowing your life might be on the line made the stakes even higher.

Today, remnants of ball courts dot Mesoamerica, standing as haunting reminders of a sport where victory and survival were often intertwined.

7. Chocolate as Currency: Divine and Delicious

You walk into a bustling marketplace in Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, and instead of coins jingling in pockets, traders pass around cacao beans. Need a turkey? That’ll cost 100 beans. A tamale? Just three. In Mesoamerica, chocolate wasn’t just a treat — it was wealth.

The Maya were among the first to cultivate cacao, considering it a gift from the gods. The Aztecs took it a step further, turning the beans into a form of currency. But cacao also held immense religious significance. Priests drank chocolate in sacred rituals, often mixing it with chili, maize or honey. This wasn’t your typical hot chocolate, though; it was a frothy, bitter elixir meant to connect mortals with the divine.

For the Aztecs, chocolate represented luxury, spirituality and power. Its association with the gods elevated it beyond mere sustenance, making it a cornerstone of their economy and culture.

8. Chinampa Floating Gardens: Ancient Environmentalism

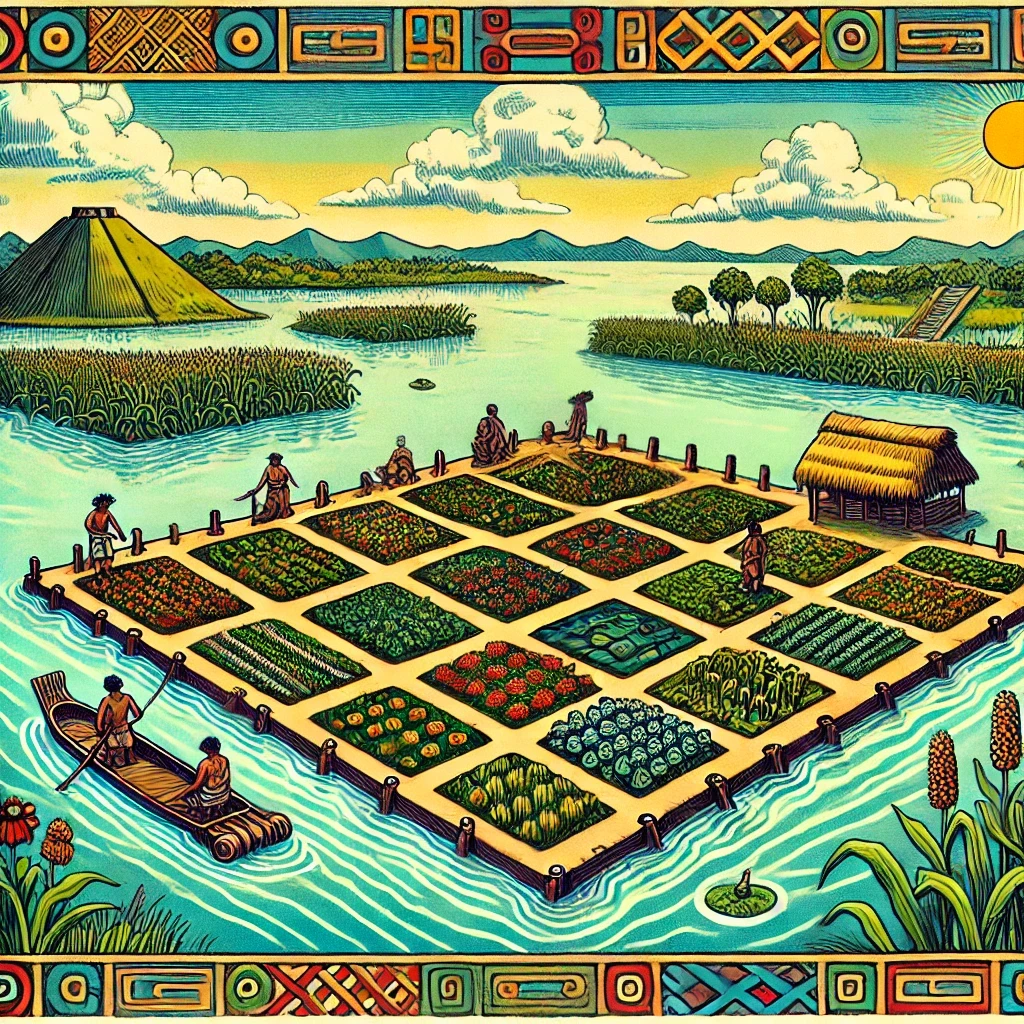

Faced with limited farmland, the Aztecs invented chinampas — ingenious floating gardens — to feed their massive population. You can still glide through some of the original canals at Xochimilco, where this ancient innovation lives on.

Chinampas were artificial islands made of woven reeds and mud, anchored in the shallow lakes around the city. These gardens were incredibly fertile, producing crops like maize, beans, squash and flowers. A single chinampa could yield up to seven harvests per year, an efficiency unmatched even by today’s standards.

The Aztecs created a self-sustaining ecosystem, where canals provided irrigation and fish fertilized the soil. Modern scientists marvel at the environmental brilliance of chinampas, which could inspire solutions to today’s agricultural challenges.

9. Astronomy: The Stars Were Their Guide

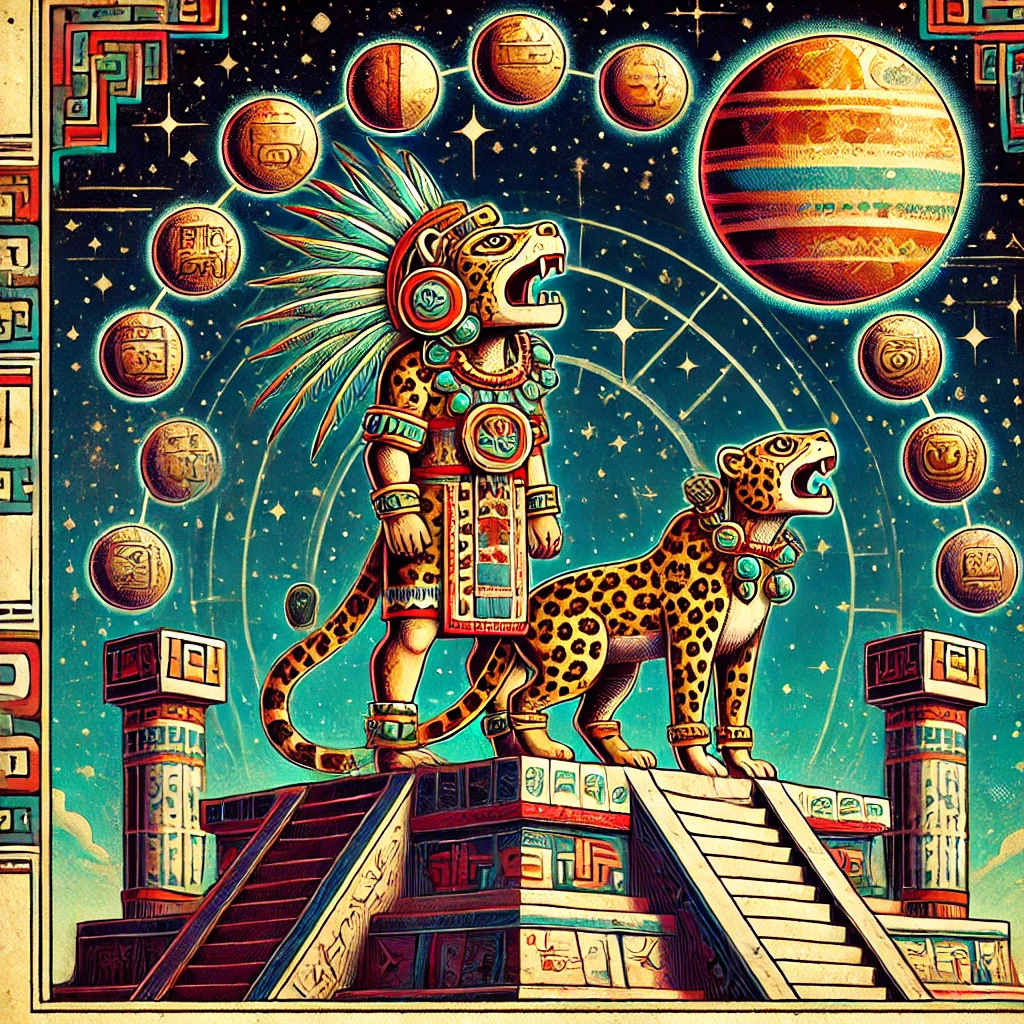

It’s midnight in a Maya city, and the stars shine brightly. A priest, adorned in jaguar pelts and jade, carefully watches the movements of the planet Venus. For the Maya, astronomy was a divine map, guiding everything from farming to warfare.

Maya astronomers meticulously tracked celestial bodies, creating some of the most accurate calendars in human history. Their Long Count calendar, famously misinterpreted as predicting the world’s end in 2012, was a tool for tracking vast stretches of time. They predicted eclipses with stunning precision and understood the 584-day cycle of Venus, which they associated with war and sacrifice.

Cities like Chichen Itza in modern-day Mexico were aligned with celestial events, such as the equinox. On these days, the shadow of the sun forms a serpent slithering down the temple of Kukulkan. For the Maya, this was a powerful reminder that the gods were always watching — and that humanity’s actions were written in the stars.

10. Advanced Mathematics: Zeroing In on Genius

While medieval Europe was fumbling with clunky Roman numerals, the Maya were crafting a sophisticated base-20 numerical system centuries ahead of their time. Even more groundbreaking, they independently invented zero, a concept that revolutionized mathematics across the world.

The Maya used their numerical system for everything from complex architecture to astronomical calculations. Their hieroglyphs represented numbers with dots and bars, and a shell symbol for zero — a groundbreaking idea that enabled them to calculate vast stretches of time. This mathematical prowess was essential for creating their famous calendars, which tracked both earthly and cosmic cycles.

11. Burial of Kings in Pyramids: A Royal Afterlife

Deep inside a pyramid in Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico, archaeologists uncovered the tomb of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, one of the greatest Maya rulers. His jade death mask gleamed in the flickering torchlight, surrounded by treasures meant to guide him into the afterlife. For the Maya, burial honored the dead in their journey to the underworld, a sacred act steeped in ritual and grandeur.

Unlike the Egyptians, who mummified their rulers, the Maya focused on elaborate tombs. These often included jade ornaments, intricate carvings, and offerings of food, pottery and incense. Pakal’s sarcophagus lid, for example, depicts him descending into the underworld, surrounded by mythological imagery that tells the story of his divine lineage.

These tombs weren’t just graves; they were political statements. By aligning their burials with religious symbolism, rulers reinforced their connection to the gods, ensuring their legacy endured both on Earth and in the spiritual realm. Each pyramid was a monument that acted as a doorway between worlds.

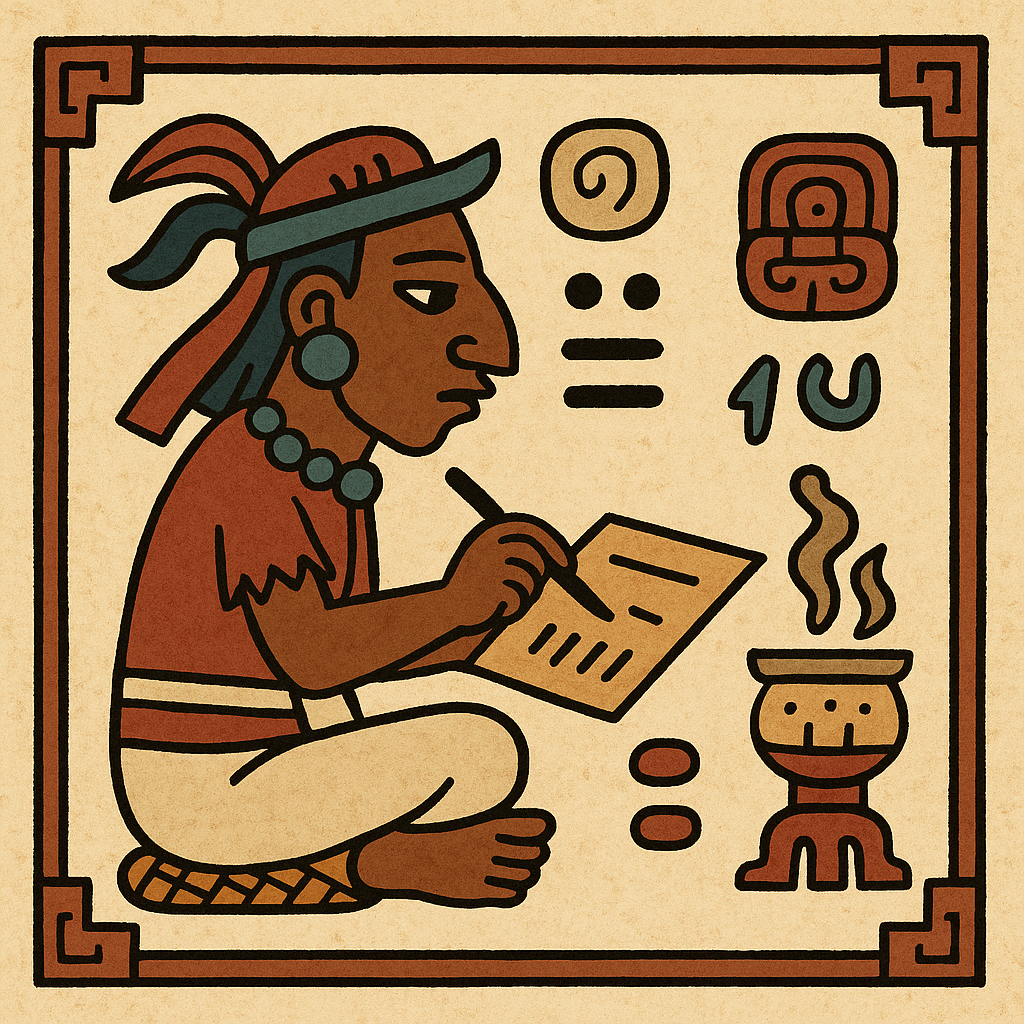

12. Codices: Books of the Gods

Imagine holding a book that contains the secrets of the universe, the history of kings and the rituals to summon rain. That’s what Mesoamerican codices represented: sacred texts painted on bark paper or deerskin, filled with colorful glyphs and stunning illustrations.

The Aztecs, Maya and Mixtec used codices to record everything from genealogy to religious ceremonies. These books were read by priests and rulers, who used them to guide decisions and communicate with the divine. Sadly, the Spanish destroyed the vast majority of these texts during the conquest, believing them to be works of the devil. Of the thousands of codices once created, only a handful survive today, including the Dresden Codex and the Codex Borgia.

Each surviving codex offers a glimpse into a lost world, revealing the complexity of Mesoamerican thought and artistry. These were living documents, bridging the human and the divine. The destruction of these texts remains one of the greatest tragedies of the conquest, a loss of knowledge we can only begin to fathom.

13. Hallucinogens in Rituals: Unlocking the Divine

The fire crackled in the dim light of the temple, smoke swirling around a priest seated cross-legged, a small cup of pulque — a fermented agave drink — in one hand and a bundle of morning glory seeds in the other. As he consumed the seeds, his breathing slowed, his vision blurred, and he began to see the gods. For the Maya, Aztecs and other Mesoamerican cultures, hallucinogens weren’t recreational; they were sacred tools, gateways to the divine.

Psychoactive plants like peyote, psilocybin mushrooms and the seeds of morning glory vines (tlitliltzin) played a central role in ceremonies. Priests and shamans believed these substances opened pathways to cosmic truths, allowing them to communicate with deities, interpret omens and guide their communities. The experience was deeply spiritual, often accompanied by chants, prayers and rhythmic drumming, reinforcing the connection between the mortal and divine.

Modern scientists have confirmed the psychoactive properties of these plants and their ability to alter consciousness. Even today, the Mazatec, descendants of the ancient Mixtec, continue rituals involving hallucinogens, preserving their connection to the sacred.

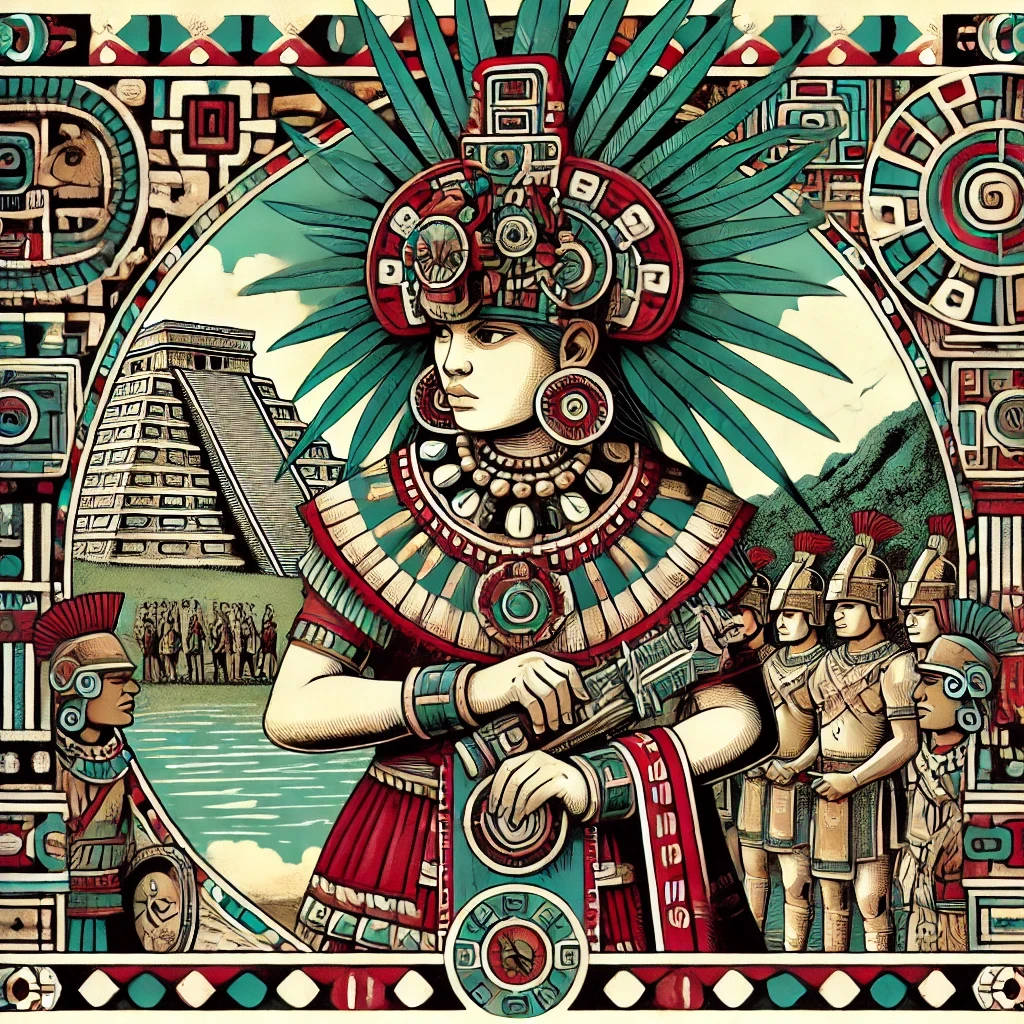

14. Women as Leaders: Power in Unexpected Places

The Mesoamerican world is often painted as a patriarchal society, dominated by kings and warriors. But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find powerful women shaping history from the shadows — and sometimes, from the throne.

In Maya society, women could rule in their own right. Lady Six Sky of Naranjo, for example, was a queen who led military campaigns and revitalized her city’s influence. And in Mixtec culture, women were often depicted as priestesses, warriors and even co-rulers, standing alongside men in both politics and religion.

These women were integral to the fabric of their societies. While their stories are often overshadowed by their male counterparts, their legacies endure in ancient texts, carvings and oral traditions.

15. Trade Networks: A Marketplace Across the Americas

Picture a bustling marketplace where merchants trade obsidian from central Mexico, turquoise from the American Southwest, and feathers from tropical jungles. This was the Mesoamerican trade network — an intricate web of commerce that connected cultures across thousands of miles.

The Aztecs had professional traders called pochteca, who ventured into distant lands to bring back luxury goods as well as information. These merchants doubled as spies, gathering intelligence for the empire. Goods exchanged included cacao, salt, jade, textiles and live animals like macaws.

The Maya, meanwhile, traded along rivers and coastlines, using massive dugout canoes to transport goods.

These trade networks reveal a highly interconnected world, centuries before European contact. They weren’t just exchanging items but also ideas, technologies and cultural practices. Innovation wasn’t confined to one city or empire, but was shared across Mesoamerica, creating a vibrant, collaborative civilization.

16. Flower Wars: Fighting for Sacrifice Victims

In the Aztec world, war wasn’t always about conquest — it was about feeding the gods. Known as flower wars, these prearranged battles were fought not to expand territory but to capture prisoners for sacrifice. Think of it as a grim, divine version of capture the flag.

The idea behind a flower war was simple: The gods required blood to sustain the universe (see above), and the noblest offering was a captured warrior. These battles were fought with precision and ritual, often involving ornate costumes and weapons designed to wound rather than kill. The goal wasn’t to destroy the enemy but to bring back their strongest fighters as living sacrifices.

This practice highlights the unique relationship between war and religion in Aztec society. For them, the battlefield was sacred ground, where the fate of the cosmos was decided. The concept of flower wars reveals the Aztecs’ belief in sacrifice as an honorable exchange between mortals and gods, where even the defeated played a crucial role in cosmic harmony.

17. Urban Centers of Stone: Predating European Cities

Before London had cobblestone streets or Paris had a skyline, cities like Teotihuacan in central Mexico were thriving metropolises. With a population that likely reached over 200,000 at its peak, Teotihuacan was one of the largest cities in the ancient world, rivaling the size of Rome.

Teotihuacan, whose name means “The Place Where Gods Were Created,” was meticulously planned. It boasted wide avenues, towering pyramids, multi-story apartment complexes and a sophisticated drainage system. The Pyramid of the Sun and Pyramid of the Moon dominated the skyline, their purpose tied to celestial events and rituals. Meanwhile, smaller neighborhoods housed artisans, merchants and farmers, creating a cosmopolitan hub of culture and commerce.

What’s even more impressive? Teotihuacan’s influence spread far beyond its borders, shaping the cultures of the Maya, Zapotec and others. Archaeological evidence suggests its trade routes extended thousands of miles, making it not just a city but a cultural and economic powerhouse. Its sophistication proves that long before European colonization, Mesoamerica had already mastered the art of urban living.

18. Advanced Water Management: Engineering Marvels

In Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, advanced water management turned a swampy island into a thriving metropolis.

The Aztecs built aqueducts to bring fresh water into the city from nearby springs, ensuring a reliable supply for drinking, bathing and irrigating crops. They also constructed dikes and canals to control flooding during the rainy season. One of the most remarkable projects was the dike built by the engineer Nezahualcoyotl, a massive barrier that separated fresh and brackish water in Lake Texcoco.

These innovations allowed Tenochtitlan to support a population of over 200,000 people — comparable at the time to Paris, Constantinople and Beijing. The city’s water management was practical as well as beautiful, with canals crisscrossing neighborhoods and floating gardens providing food and greenery.

19. The Aztec Love for Pets: Companions of Life and Death

While many associate the Aztecs with grand temples, fierce warriors and intricate rituals, they also had a tender side: their deep connection to animals. Domesticated dogs, particularly the Xoloitzcuintli (Xolo), held a special place in Aztec society. These hairless dogs were believed to guide their owners’ souls through the underworld to Mictlan, the final resting place for most Aztecs. Often, these loyal companions were buried alongside their owners to fulfill this sacred role. (Xolos were also a favorite food at special feasts like weddings.)

But dogs weren’t the only animals cherished by the Aztecs. Turkeys (huehxolotl), macaws and parakeets were kept as pets, not solely for their feathers or meat, but also for companionship. Macaws, with their bright plumage, were often seen as symbols of beauty and vibrancy, while turkeys held religious significance. These animals frequently appeared in Aztec art, codices and ceremonies, bridging the connection between the natural and spiritual worlds.

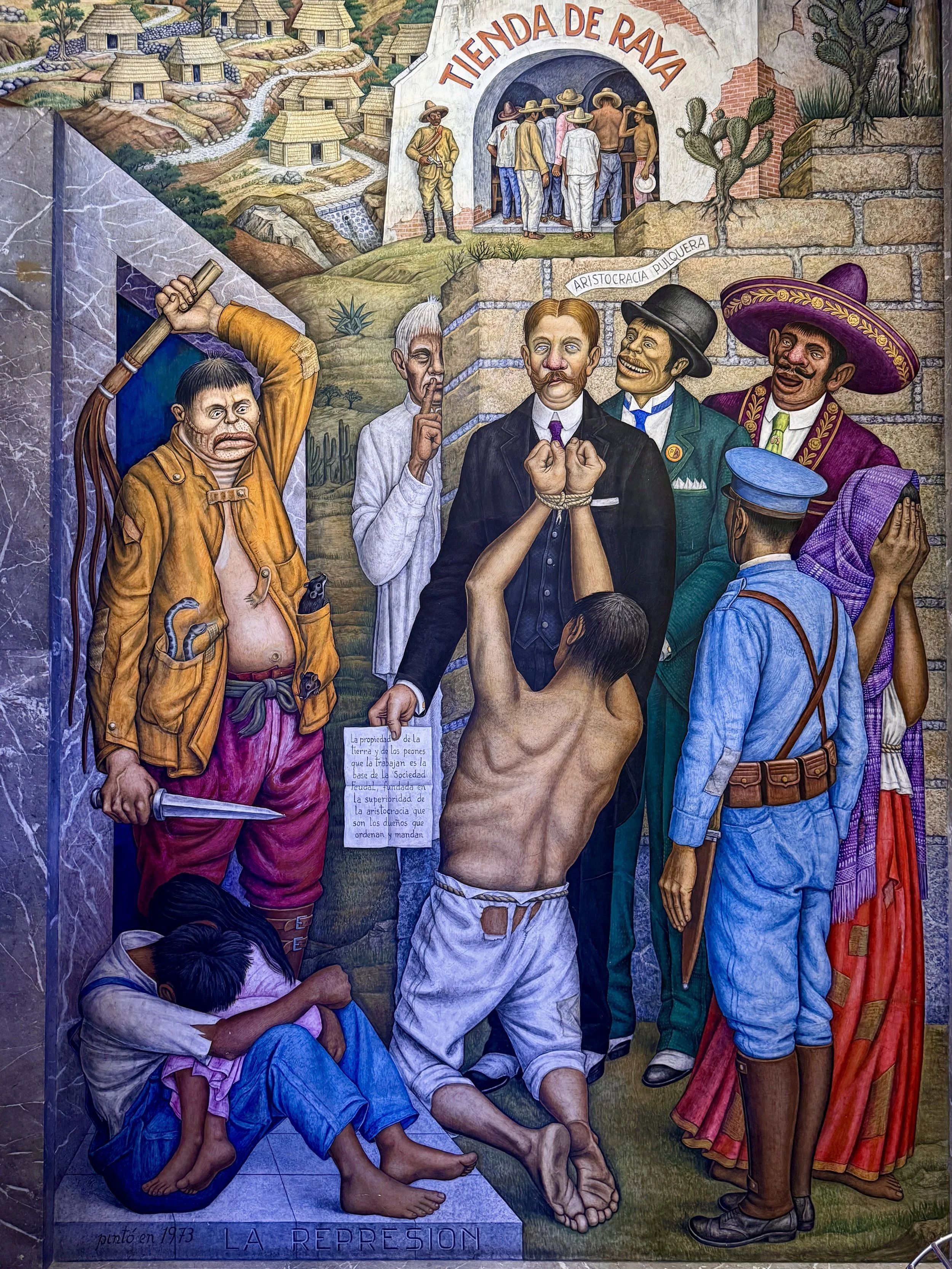

20. Resistance to Colonization: A Legacy of Defiance

When Hernán Cortés marched into Mexico in 1519, he may have toppled the Aztec Empire, but indigenous resistance didn’t end there. The Maya, for example, fought Spanish domination for centuries, with conflicts like the Caste War of Yucatán lasting well into the 19th century.

One of the most remarkable stories of defiance comes from the Maya city of Tayasal, which remained independent until 1697 — nearly two centuries after the fall of Tenochtitlan. Using guerrilla tactics and their knowledge of the jungle, the Maya outlasted wave after wave of Spanish expeditions. Even after their cities were conquered, they preserved their culture through language, art and traditions, subtly resisting assimilation.

Despite centuries of conquest and colonization, their legacy lives on — not just in history books but in the vibrant traditions and identities of modern Mexico and Central America.

Like Blood for Chocolate: What Mesoamerica Left Behind

The civilizations of Mesoamerica built stunning pyramids and created impressive calendars. They were innovators, dreamers and survivors. Their world was one of astonishing ingenuity, spiritual devotion and cosmic balance. While some aspects of their culture may seem shocking to us today, they remind us that history isn’t always comfortable — but it’s always worth exploring. –Wally