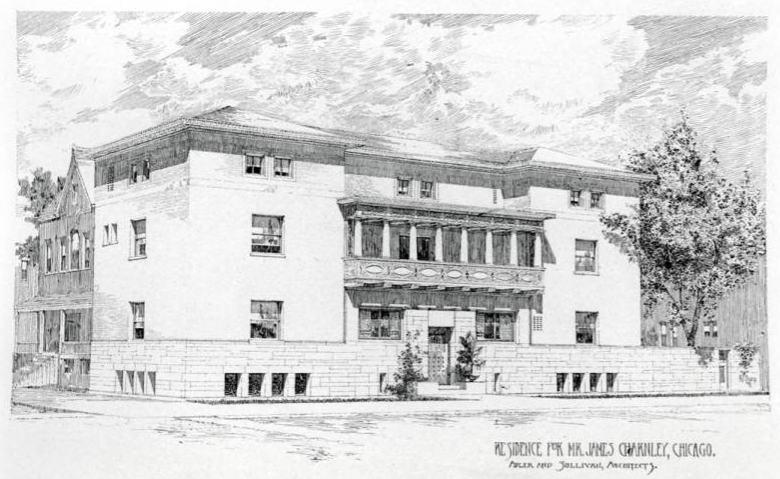

Wright’s American System-Built Homes still stand on Burnham Block, a quiet testament to his dream of housing for the middle class.

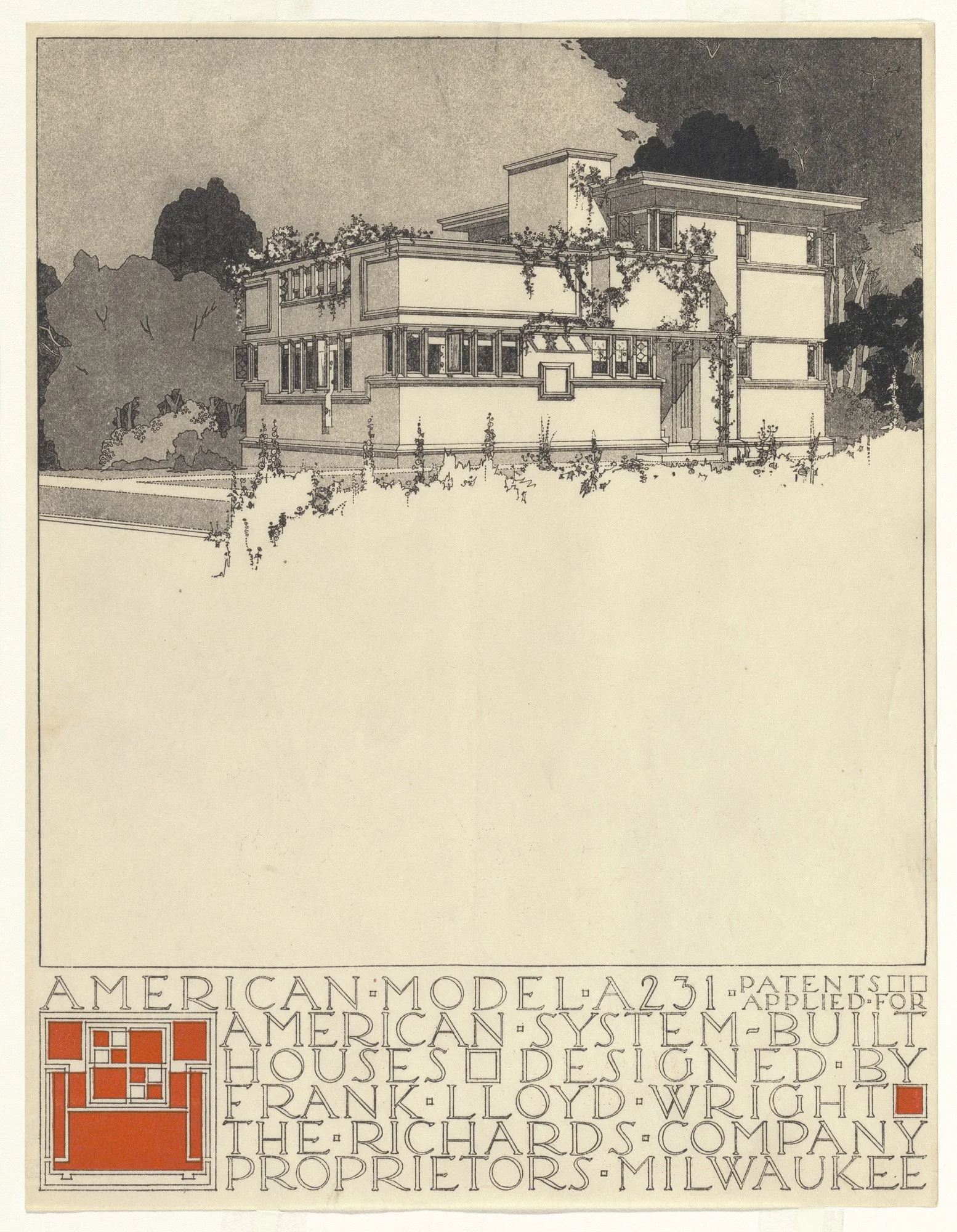

Well before he designed Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, Wright poured his energy into a very different kind of project — producing more than 900 drawings and over 30 standardized model variations for the American System-Built Homes: a line of modest, affordable houses for America’s middle-class families.

So when Wally and I planned a long weekend in Milwaukee, one of our top priorities was visiting the Burnham Block. Tucked between 27th Street and Layton Boulevard, this quiet stretch of West Burnham Street is home to six of Wright’s homes — examples of one of the most ambitious design efforts of his career and the largest collection of this housing style in the country.

“At just 805 square feet, it’s the smallest of any house Wright designed.”

Fun fact: The thoroughfare was named after George Burnham, a brick manufacturer and real estate investor in the city. The cream-colored bricks his company produced helped give Milwaukee its nickname, the Cream City.

“An American Home”

After snapping a few photos outside, Wally and I ducked into the gift shop at the back of one of the duplexes currently undergoing restoration. From there we made our way to the front room to join our tour group and meet our docent, Rhonda. Once everyone was settled in, she broke the ice by asking where we were all from, and to our surprise, one family had traveled all the way from Italy.

She asked the group to imagine what a real estate ad might highlight today, and we quickly called out the usual features: square footage, number of bedrooms, location and price — basically everything related to the building itself.

Holding up a full-page advertisement that ran in the Chicago Tribune in July 1917, titled “You Can Own an American Home” and attributed to then-copywriter Sherwood Anderson, she read the following excerpt aloud:

“There’s a bright, cheerful home waiting for you and your family — better built, excellently planned, far more livable. More beautiful? Yeah, it’ll have that rare thing: genuine architectural beauty, designed by a leader among architects. You select your plan; it’s built to your order. Constructed by a system that guarantees a high-grade building at a known price. In short, an American home.”

Rhonda pointed out that it wasn’t really about any of the features we had mentioned; it was about selling a lifestyle. And one big thing the ad omitted? Wright’s name — and that was no accident.

Wally’s last name is also Wright, but, sadly, he’s never found a familial link to Frank.

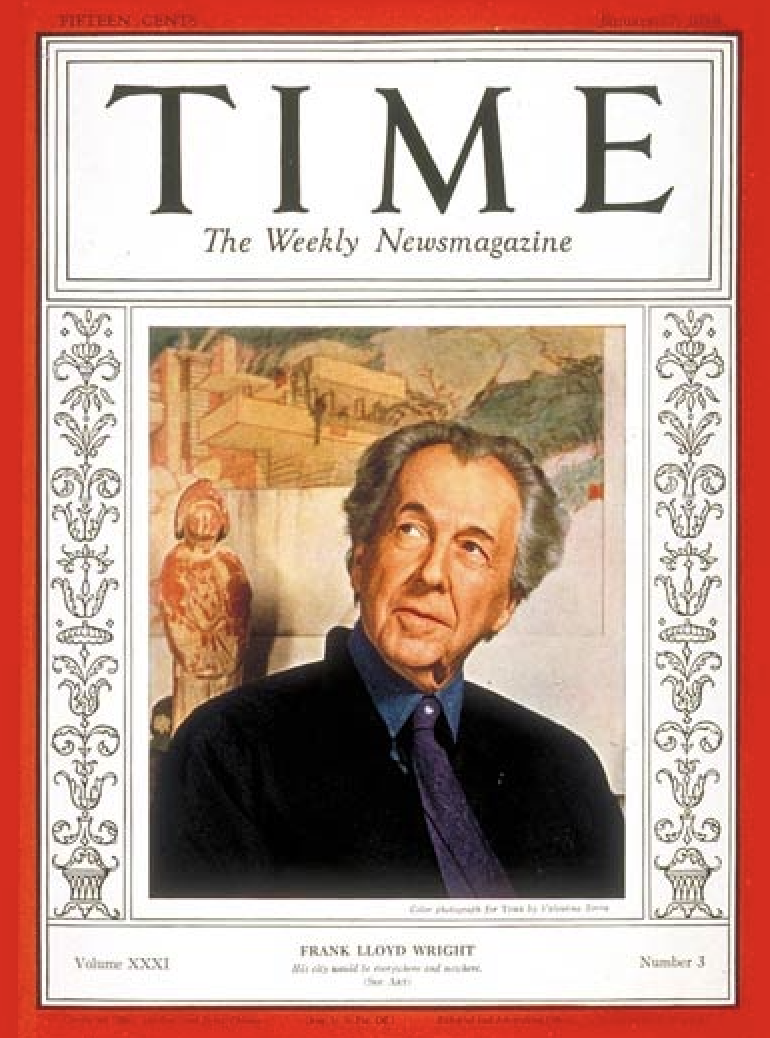

When “Wright” Was a Bad Word

By 1915, the architect’s personal life had become tabloid fodder. In 1909 he had famously abandoned his wife and six children to run off to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney — the wife of a former client and the woman at the center of a scandalous, widely publicized affair.

Both were still married to their respective spouses when they left. Mamah got a divorce from her husband when they returned, but Wright wouldn’t officially be divorced from his wife, Catherine, for another six years.

The scandal deepened in 1914, when a servant at Taliesin — Wright’s home and studio in Wisconsin — set fire to the building and axed down Mamah, her two children, and four others as they fled the flames. The tragedy made front-page headlines and further tarnished Wright’s reputation.

Rhonda went on to explain that what most people don’t realize is just how deeply Wright believed in what he called “democratic architecture.” To him the idea was simple: If you had a good job, you should also be able to afford a thoughtfully designed home. But Wright, for all his vision, didn’t quite know how to make that dream scalable.

A Partnership With Arthur Richards

That's where Milwaukee developer Arthur L. Richards came in. He had previously collaborated with Wright on the Hotel Geneva, a lakeside resort that once stood on the shores of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Richards had the resources and business network Wright lacked, and he was able to turn the architect's vision into a viable housing project.

Assuming the advertisement piqued your curiosity, your next stop would be to visit a local distributor. At the time, many young families were buying homes from the pages of mail-order catalogs — think Craftsman-style kits sold by Sears, Roebuck and Co.

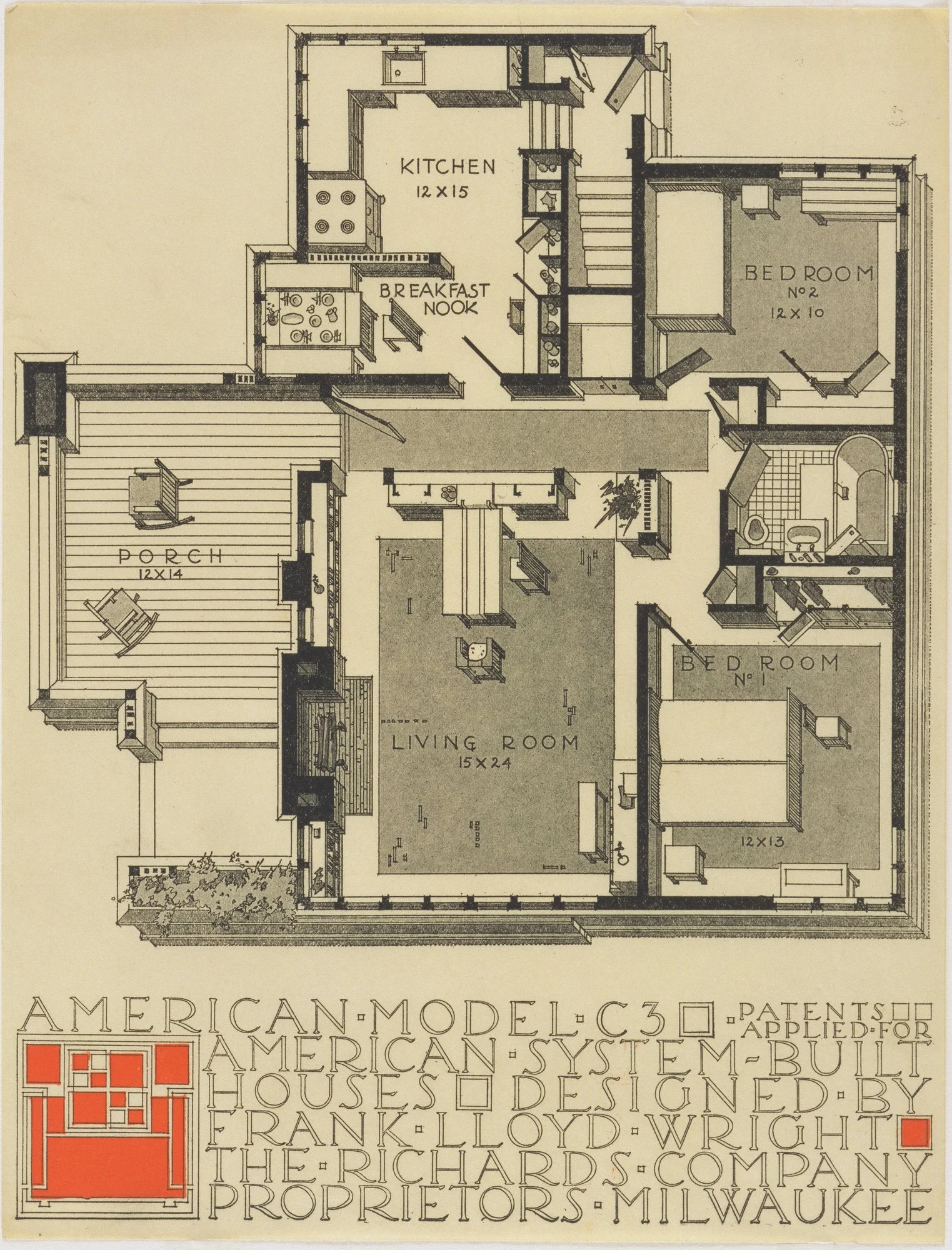

But Wright’s American System-Built Homes were different. They were modern, meticulously detailed, and built to his exacting standards. Customers could choose from roughly 30 standardized models, each offering a range of customizable options, including the floor plan, roof style (flat, hip or gable), custom furniture and art glass windows. You added up your choices, saw the total at the bottom, and that’s what you paid.

Prices started at $1,875 and rose to about $3,500 once completed — remarkably modest for any home, much less a Wright-designed one, especially given his reputation for commissions that routinely ran over budget. It may sound like a lot for 1915, but homes of comparable size and quality typically sold for 10% to 15% more. This relative affordability was largely due to Richards, whose oversight kept costs down and brought Wright’s designs to a broader market.

To achieve this, the Richards Company pre-cut lumber and other materials in a mill and shipped them to the build site by rail — a method that offered greater efficiency and quality control than traditional site-built construction.

Preserving a Legacy: Restoration Efforts at Burnham Block

Once we had a sense of the project's background, Rhonda led us outside and enthusiastically shared more about this row of homes’ history and significance. Built on speculation between October 1915 and July 1916 the block includes four two-family Flat C (Model 7A) duplexes and two single-family bungalows: one Model B1 with a flat roof and one Model C3 with a hipped roof.

She highlighted the importance of ongoing preservation efforts, noting that five of the six houses are now owned by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Burnham Block, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the care and stewardship of these historic structures.

“There’s no paid staff,” she told us. “We’re all volunteers. Every single dollar you spend, whether it’s on admission, in the gift shop or as a donation goes directly toward the care of these buildings.”

She went on to explain that the exterior of Duplex 4, the building we had just exited, was restored in 2013 and 2014 with the help of a Save America’s Treasures matching grant. The grant was awarded by the Department of the Interior and is managed by the National Park Service to support the preservation of nationally significant historic sites. Work on the interior, she noted, is still underway.

“We did get a grant from the government,” she added. “But we’re unsure if we’ll actually receive that money. So for now, we’re kind of on hold, waiting to see what happens.” The hope is that they’ll be able to start restoration efforts on Bungalow Model C3 this year.

When Richards selected the site for the housing project, it was considered the edge of town — still largely rural and known for its celery fields. An electric streetcar line ran along Burnham Street, connecting the area to the rest of the city. The City Service line provided access to downtown Milwaukee, while the Interurban line extended as far as East Troy. At the time, most people didn’t own cars, but they had access to mass transit, one of the key reasons these homes were built here.

We paused for a moment in front of 2720 West Burnham Street — the only duplex on the block that isn't owned by the nonprofit.

Rhonda gave us a quick rundown of its history, explaining that a young couple who knew the legacy of the two-flat purchased the property in the early 1980s and converted it into a single-family home with three bedrooms, two bathrooms and a modern kitchen. She added that they installed the art glass windows and red square, a visual element found in many of Wright's designs. Nearly 30 years later, it was sold to its current owner, who now rents it out on Vrbo.

“I’ve been told it sleeps about nine — so if you decide to rent it, don’t forget to invite me!” Rhonda added with a chuckle.

A Tour of Model B1

A short walk later, we found ourselves standing outside Model B1 at 2714 West Burnham Street. Rhonda affectionately referred to it as the “baby bungalow,” and at just 805 square feet, it’s the smallest of any house Wright designed. It was purchased in 2004 and fully restored to its 1916 appearance in 2008 and 2009. Today, it’s open to the public as a house museum.

Rhonda shared that the home’s original exterior, like the others, was finished with a material called Elastica stucco. It was manufactured in Chicago and promoted at the time as an affordable and durable option. Initially praised for its smooth appearance, it later proved unreliable and was found to contain asbestos, requiring careful remediation during restoration.

Today, the exterior has been refinished with Pebble Dash — a type of stucco embedded with small stones that are sprayed onto the surface while it’s still wet. The result is a tactile, durable façade that honors the original intent while complying with modern safety standards.

Wright’s Bag of Tricks

Before we even stepped through the front door, we passed beneath a low overhang that extended above the entrance, an unmistakable hallmark of Wright’s design philosophy. It was a classic example of his compress-and-release technique: a moment of spatial compression at the threshold that heightened the sense of openness and volume once inside.

Crossing that threshold, we entered the living room, the heart of the home, where a central hearth commanded attention. More than just a source of warmth, it was another signature of Wright’s architecture: a symbolic and literal centerpiece meant to anchor family life.

At the front of the room, floor-to-ceiling windows brought in natural light and made the space feel larger. Thanks to the height and placement of the front porch, anyone seated inside could enjoy a sense of openness and connection with the outdoors while still maintaining a sense of privacy, as the porch blocks direct views from passersby.

This sense of openness was made possible, in part, by Wright’s innovative use of balloon-frame construction, a technique where long vertical studs run continuously from the foundation to the roof. In the American System-Built Homes, these studs are spaced 24 inches apart — wider than the typical 16 inches — based on a 2-foot modular grid. This grid made it easier for Richards’ team of builders to position them with greater flexibility, without needing to rework the structure of the walls.

Rhonda pointed out that Wright’s design pulled out all the stops to make this tiny house feel larger than it is. By cleverly “stealing space,” the walls flanking the wraparound hearth draw the eye back toward the foyer and the hallway beyond, creating a sense of depth and openness.

She also noted that most of the woodwork inside the house is original. While telling us about the built-in cabinetry in the living room, she explained that it not only acts as a partition but also cleverly accommodates a dining table that can be tucked away or pulled out — transforming the living room into a dining area as needed.

To the right of the built-in, a doorway leads to the breakfast nook and kitchen. Vertical wooden slats separate the nook, offering a sense of division without fully enclosing the space, another subtle feature that reinforces an overall feeling of openness.

The kitchen was fitted with wood cabinetry and the most adorable tiny oven I’d ever seen.

Rhonda added that the glass fronts on the upper cabinets were intentional: designed to catch and reflect light, they help create the illusion of a larger, airier room.

The private space of the home includes the primary bedroom, a children’s bedroom, a bathroom, and both coat and linen closets (a rare feature in a Wright home). A central light well draws natural light into the core of the house, brightening the interior.

In the primary bedroom, ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints reflect Wright’s long-standing admiration for Japanese art and design, while the children’s room features charming illustrations created by his younger sister, Maginel Wright Enright.

An American Dream That Never Caught On

This development embodied a bold vision of the American Dream. These homes weren’t just places to live; they were a blueprint for how entire neighborhoods of affordable, well-designed housing might take shape across the country.

That vision extended far beyond this single block. Wright was never one to think small, and he and Richards imagined these homes not as a one-off experiment but as the beginning of something far-reaching. They envisioned entire subdivisions filled with variations on these models, stretching across the U.S. and into Canada. If everything went according to plan, the project could generate more than a million dollars in revenue.

The six homes on Burnham Street were completed on July 5, 1916 — just 10 days before Milwaukee hosted a massive Preparedness Parade in support of U.S. involvement in World War I. But the war would soon derail Wright and Richards’ ambitious plans. As building materials were diverted to the war effort and the housing market grew uncertain, their grand project ground to a halt.

In the end, only about a dozen American System-Built Homes were ever constructed — six on Burnham Street and a handful of others scattered throughout the Midwest. Eventually, Wright and Richards had a falling out, culminating in Wright successfully suing Richards for non-payment. Under their agreement, Wright was to receive royalties for each house sold. But a major flaw in the arrangement was that Richards wasn’t required to report each sale to Wright, making it impossible for Wright to know how many homes were actually built. That lack of transparency, combined with missed payments, led to growing mistrust and ultimately ended their partnership.

Although the Burnham Block is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, discovering the homes felt like stumbling upon a hidden gem. These aren’t the Wright homes that capture a lot of attention.

Tours are available by reservation only and are led by trained docents who offer insight into the history and design of the homes. –Duke

Before You Go

Phone: 414-368-0060

Admission: $20; children under 16 free

Times: Tours at 11 a.m., 12 p.m., 1 p.m. and 2 p.m.

Tours last about one hour.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Burnham Block

2732 West Burnham Street

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

USA