This powerful global exhibition traces the emergence of queer identity through more than 300 artworks — at a time when LGBTQ+ visibility matters more than ever.

Peace 1 by Zhang Huan, 2001

When Wally and I heard about The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869–1939 at Wrightwood 659, we were immediately intrigued. We had missed the first iteration, which ran in 2022. This new presentation promised to be larger in scale, and suggested something truly ambitious — a visual journey recontextualizing art history by presenting a wide range of works through a queer lens.

This exhibition is especially important because it comes at a perilous time when LGBTQ+ voices are increasingly under attack across political and cultural spheres. In the face of bans, restrictions on school curricula, and renewed efforts to limit or erase queer visibility, The First Homosexuals reclaims that space by affirming that queer identity has an enduring, complex and creative legacy.

““The First Homosexuals” is especially important because it comes at a perilous time when LGBTQ+ voices are increasingly under attack across political and cultural spheres. ”

I was reminded of Masculin/Masculin, a provocative exhibition Wally and I saw at the Musée d’Orsay in 2013. Drawing primarily from European painting and sculpture, the show turned the traditional male gaze on its head — shifting the focus from the female form, so often idealized in art, to the male nude. By presenting works from 1800 to the early aughts, the show invited viewers to reconsider the male body, not just as a symbol of strength or virility but as an object of desire.

While Masculin/Masculin traced the idealization of the male body in European art, it didn’t place those depictions within the broader context of queer history. The First Homosexuals at Wrightwood 659 takes that next step, expanding the lens across five continents and inviting viewers to consider queerness as something shaped by history, society and culture — often coded, but always present.

The First Homosexuals included more than 300 works by 125 queer artists from 40 countries.

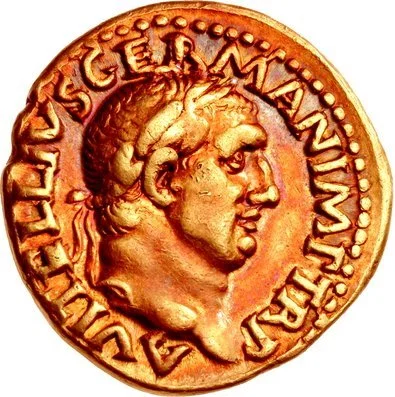

Its point of departure is 1869, when Karl-Maria Kertbeny, an Austrian-Hungarian writer and activist, introduced the term “homosexual” anonymously in a German pamphlet advocating reform of Prussian sodomy laws — a linguistic turning point that shifted same-sex love from act to identity.

You’ll definitely need to book ahead (and book early) when you see a show at Wrightwood 659.

Our Arrival at Wrightwood 659 in Lincoln Park

After breakfast at one of our favorite spots, the Bourgeois Pig, Wally and I strolled up the leafy stretch of Wrightwood Avenue in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. We were surprised to find a modest four-story red brick façade at 659. But the small group forming outside and a sign promoting the exhibition reassured us that we were in the right place.

The modern concrete building attached to the exhibit space is actually the home of one of the cofounders of Wrightwood 659.

I initially assumed the gallery’s entrance was through the modern concrete cube next door — but that was actually the private residence of media entrepreneur and philanthropist Fred Eychaner and his husband, Danny Leung. Eychaner is the founder of the Alphawood Foundation, a charitable organization, and cofounder of Wrightwood 659.

Inside, a docent greeted us in the light-filled atrium and explained that the building was constructed in the 1920s as an apartment complex. Despite its external appearance, the interiors have been stripped and radically reimagined by Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

A historic apartment building was reimagined as a striking modern art gallery.

Architect Tadao Ando transformed the interior with his minimalist design.

We stood in awe of the space’s understated tranquility. Ando preserved the outer walls, which are clad in irregular, weathered Chicago common brick, an earthy contrast to the interior’s sleek geometric simplicity.

In the far corner, an Escher-like concrete staircase begins its ascent. More than just a functional connector between levels, it serves as a kind of contemplative path, guiding visitors upward in a calm, deliberate rhythm. It’s a signature Ando gesture: structure becoming experience, architecture becoming journey.

Dance to the Berdash by George Catlin, 1837

Before the Binary: Origins of Queerness

The exhibition unfolds gradually across three floors and eight thematic sections, beginning with “Before the Binary.” This gallery sets the stage for the installation’s sweeping journey, inviting viewers to reconsider how same-sex love and gender diversity have been expressed and celebrated throughout history, long before queer identity emerged in the form we recognize today.

Prior to the subjugation brought by European colonization, many non-Western cultures regarded same-sex behavior as a fluid part of life rather than a fixed identity. This changed dramatically with the arrival of colonial powers, who introduced prejudices and legal systems and cultural prejudices that criminalized same-sex relationships. Along with this intolerance came a new binary: homosexual and heterosexual — categories rooted in 19th century European science and psychology. These labels spread globally reshaping how people understood desire, identity and themselves.

George Catlin’s painting, Dance to the Berdash, depicts a ceremonial dance performed by the Sac and Fox Nation honoring a “two-spirit” individual. The term berdache, used by Catlin, is an outdated and derogatory French term historically applied to two-spirit people.

In his journals, Catlin describes the scene as “very funny and amusing,” and expresses bewilderment where a “man dressed in woman’s clothes … driven to the most servile and degrading duties” would be celebrated and “looked upon as medicine and sacred.”

Despite his evident bias, Catlin’s work offers a rare glimpse into the deeply spiritual and cultural roles that two-spirit or third-gender individuals have historically held in many Native American communities.

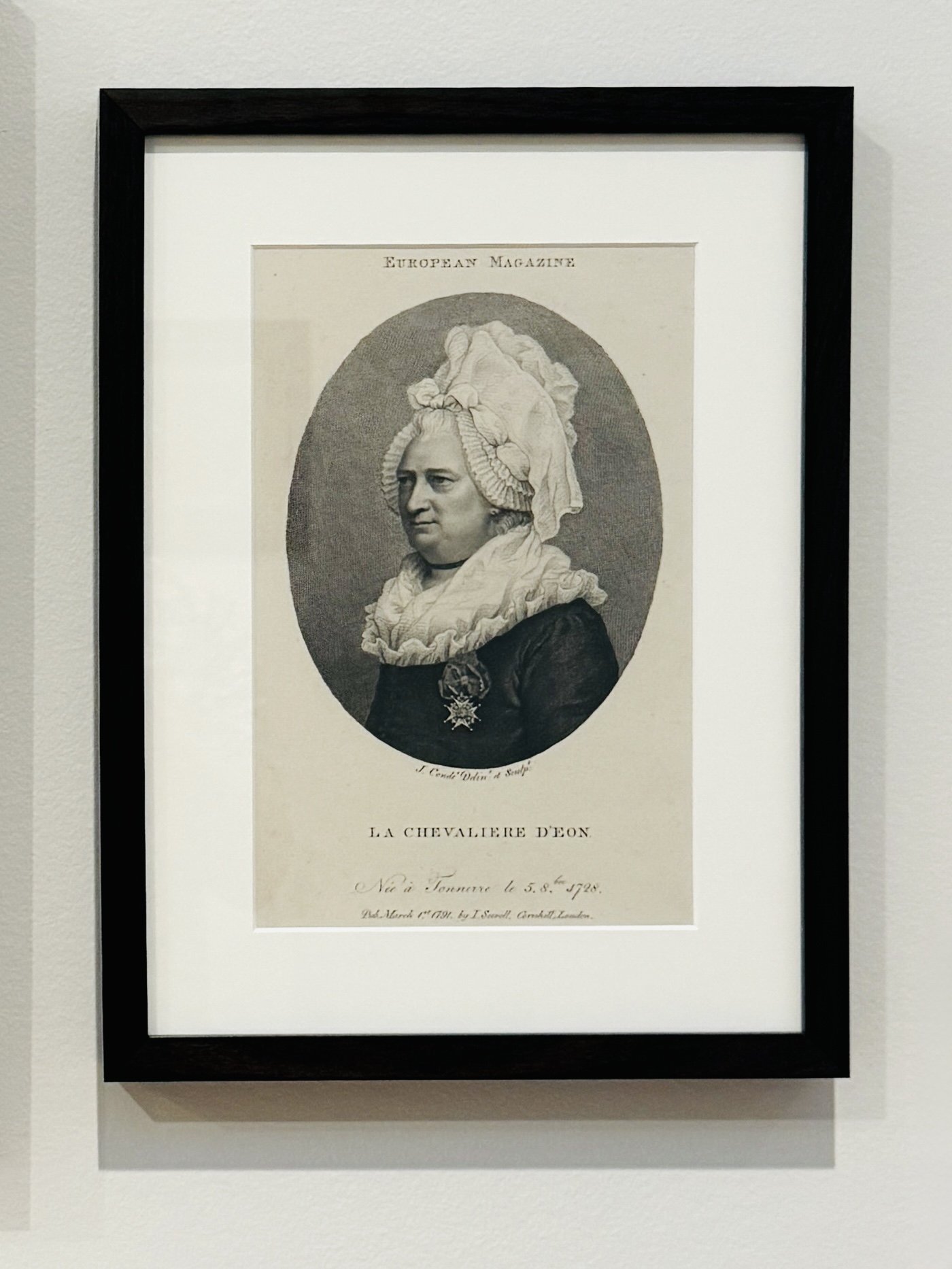

Portrait of Chevalier d'Eon by Jean Condé, published by John Sewell in a 1791 issue of The European Magazine

The Chevalière or Chevalier d’Éon (1728-1810), was an early gender-nonconforming figure and a French diplomat, spy and soldier.

In 1755, while presenting as a man, d’Éon was sent to Russia disguised as Mademoiselle Lia de Beaumont to persuade Empress Elizabeth I of Russia to ally with France against England and Prussia. From 1777 onward, d’Eon lived publicly as a woman and was officially recognized as such by King Louis XVI.

In this print, d’Éon is portrayed as a middle-aged woman wearing a dark dress with a chemisette, a lace cap and the star of the Order of St. Louis, an honor awarded for distinguished military service and espionage.

As evidence of the shifting political and cultural landscape of the era, d’Éon spent much of her adult life in London, where her gender identity was the subject of constant speculation. It was even the subject of a court trial declaring d’Éon to be a woman, though a surgeon later attested on her death certificate she had “male organs.”

Anacreon and Cupid by Bertel Thorvaldsen, 1824

Bertel Thorvaldsen’s neoclassical Anacreon and Cupid depicts the Ancient Greek poet Anacreon being struck by Cupid’s arrow, causing the older man to fall in love with the youthful god of love. The relief is inspired by Anacreon’s text, Ode III, which ends with Cupid flying away, satisfied he can still attract love with his arrows, while the poet is left alone with his longing.

The term homosexual didn’t yet exist, and art about the classical past enabled the representation of same-sex eroticism under the guise of historical reference.

The artist’s nearby ink and graphite sketch literalizes the erotic element of the sculpture, portraying Cupid fondling the poet’s groin.

In Ancient Greece, the ideal same-sex relationship was seen as one between an older man and a teenage boy. This kind of relationship was tied to ideas about teaching the younger generation how to be good citizens. Same-sex desire was accepted — but only in ways that supported the male-dominated social system.

Portrait of Rosa Bonheur by Anna Klumpke, 1898

Portraits: Icons and Outlaws

“Portraits” features artists who dared to make homosexuality visible long before it was safe or legal to do so.

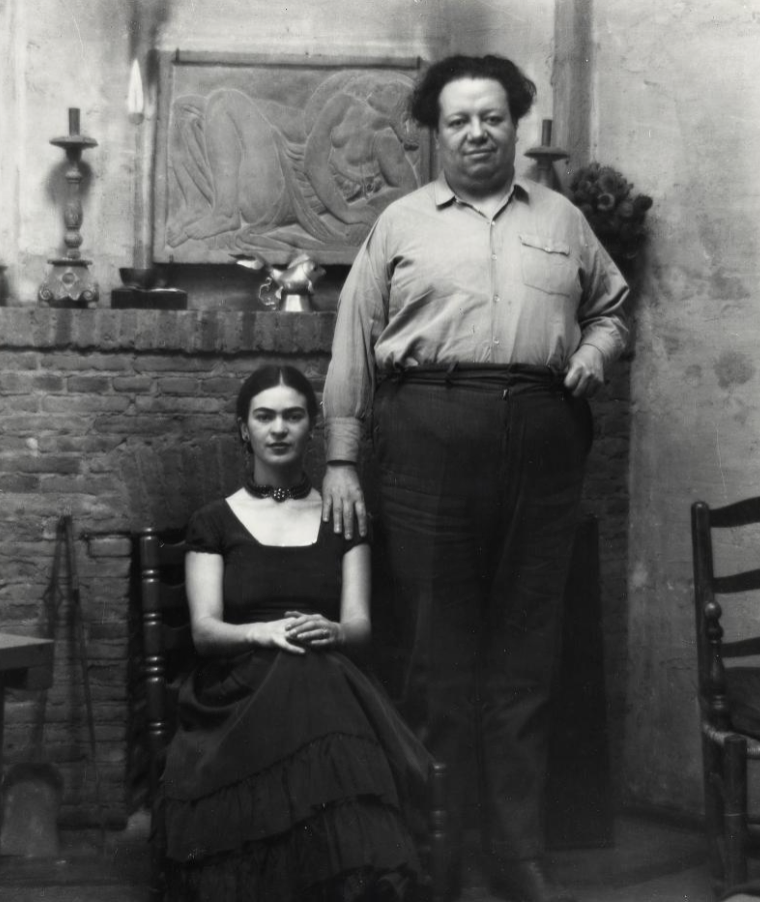

American artist Anna Klumpke’s tender pastel portrait captures her partner, Rosa Bonheur, in the final years of the celebrated French painter’s life. The two met in 1895, when Klumpke was 39 and Bonheur was 73. They soon moved in together, and their relationship endured until Bonheur’s death in 1899.

Rosa Bonheur was one of the most renowned animal painters of the 19th century. An independent woman and openly lesbian, she famously obtained official permission from the Paris police to wear men’s clothing — a permit she justified by explaining that traditional women’s attire was impractical for working in stables and slaughterhouses, where she sketched animals for her work.

By the way, there’s a delightful bar, Rosa Bonheur, in Paris, named after this icon.

Retrato de un Anticuario (Portrait of an Antiquarian) by Robert Montenegro, 1926

Roberto Montenegro’s 1926 portrait of antiques dealer Chucho Reyes is rich with visual codes that still resonate in queer iconography today — a limp wrist, a tilted chin and a wry smile. In the foreground, a silver ball subtly reflects the artist’s own face, a quiet but unmistakable act of self-insertion and queer affirmation.

An early figure in the Mexican muralist movement, Montenegro often pushed against the boundaries of revolutionary aesthetics. In a mural for the Secretaría de Educación Pública in Mexico City, his depiction of a nude, androgynous Saint Sebastian drew criticism for being out of step with official nationalist values.

Montenegro was ultimately compelled to repaint it. In his private commissions, however, he enjoyed greater artistic freedom — freedom he fully embraced in this intimate and symbolically coded portrait.

Portrait of James Baldwin by Beauford Delaney, 1944

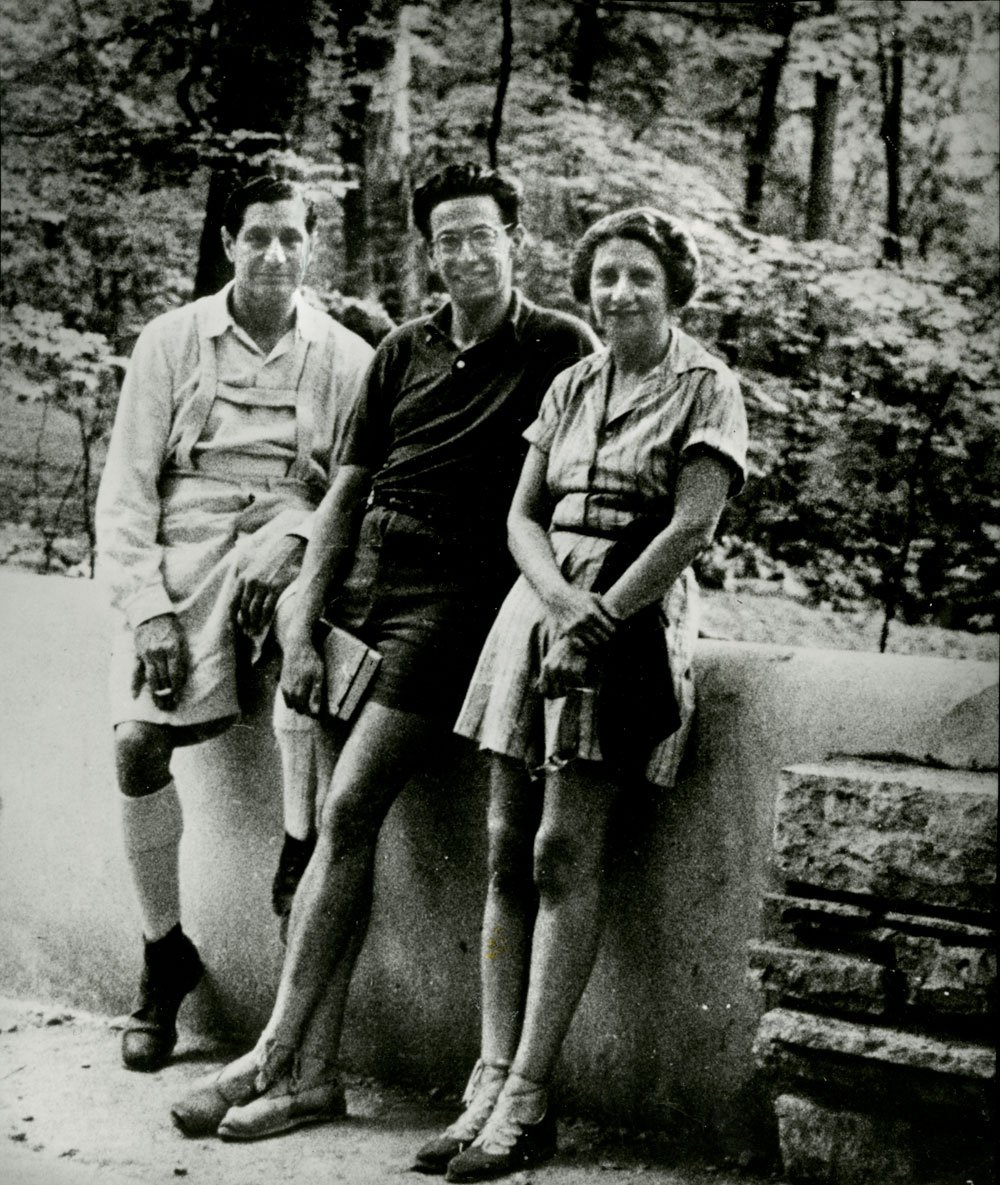

In this vibrant portrait, Beauford Delaney depicts the 20-year-old African American author James Baldwin before the writer’s rise to literary fame. Delaney renders Baldwin’s face in expressive strokes of green, yellow and purple, capturing not just likeness but inner light. The two men, both openly gay and trailblazing artists of color, shared a profound, formative bond.

Baldwin regarded Delaney as a mentor and father figure. Reflecting on Delaney’s influence, he wrote, “The reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see.”

Though Baldwin would become a powerful voice in the civil rights movement, his open sexuality often left him marginalized within the movement’s leadership.

He went on to become one of the most influential gay writers of the 20th century, penning such landmark works as Giovanni’s Room (1956).

Profile of a Man With Hibiscus Flower (Felíx) by Glyn Philpot, 1932

This intimate portrait features Felíx, a French Caribbean model who sat for the British artist Glyn Philpot several times in 1932. The composition, with its flattened perspective and floral motif, recalls Paul Gauguin’s canvas Jeune Homme à la Fleur, evoking themes of sensuality and exoticism. While the painting echoes colonial-era visual tropes, Philpot’s broader oeuvre is distinguished by its empathetic and often dignified representations of Black subjects, challenging the stereotypes prevalent in early 20th century European art.

Le Bal élégant, La Danse à la campagne (The Elegant Ball, The Country Dance) by Marie Laurencin, 1913

Relationships: Intimate Worlds

The section titled “Relationships” explores the personal and social dimensions of queer lives. From Marie Laurencin’s sensual and playful female imagery to Andreas Andersen’s portrait of his younger brother and his friend, their works reflect the sheer diversity and joy of queer intimacy.

La Danse (The Dance) by Marie Laurencin, 1919

Marie Laurencin (1883-1956), a French Cubist, created an idiosyncratic body of work that excluded men and placed women at the center, something truly revolutionary considering that she worked in Paris, in an environment dominated by male artists. A member of Pablo Picasso’s gang, Laurencin’s unique take on Cubism is particularly evident in The Elegant Ball, The Country Dance, a fragmented and angular portrayal of two women dancing front and center.

The canvas The Dance illustrates Laurencin’s departure from Cubism and marks the development of her own visual language, one that embraces a softer, more fluid style in which women’s bodies seem to merge and dissolve into one another. Laurencin’s dreamlike, ethereal compositions represent a feminist counterpoint to the stylistic tendencies of the male-dominated Cubist avant-garde.

Interior With Hendrik Andersen and John Briggs Potter in Florence by Andreas Anderson, 1894

The Norwegian painter Andreas Andersen depicts his younger brother, Hendrik and their friend, American painter John Briggs Potter, when the trio were living together in Florence in 1894. To our modern eyes, this is a stunning image of a homosexual relationship — but the reality is that men of this era didn’t think that loving or having sex with other men was abnormal or put them into a sexual category.

Potter, who eventually married a woman, was close to Isabella Stuart Gardner of the eponymous Boston museum. The exact relationship between Hendrik and Potter isn’t known, though Potter was painted by a number of known queer painters and himself painted portraits of handsome men.

Sueño marinero (Sailor’s Dream) by Gregorio Prieto, 1932

Gregorio Prieto was a member of the influential Spanish cohort known as the Generation of ’27, alongside the poet

Federico García Lorca. While his work is well known in Spain, it hasn’t received the recognition it merits.

Prieto’s two paintings exhibited at Wrightwood exemplify his use of the mannequin as a surrealist trope. Prieto employed mannequins as a metaphor for homoerotic love. Indeed, Sailor’s Dream seems to insinuate the act of oral sex, while Full Moon implies stimulation by hand.

Le Sommeil de Manon (Manon’s Sleep) by Madeleine-Jeanne Lemaire, 1907

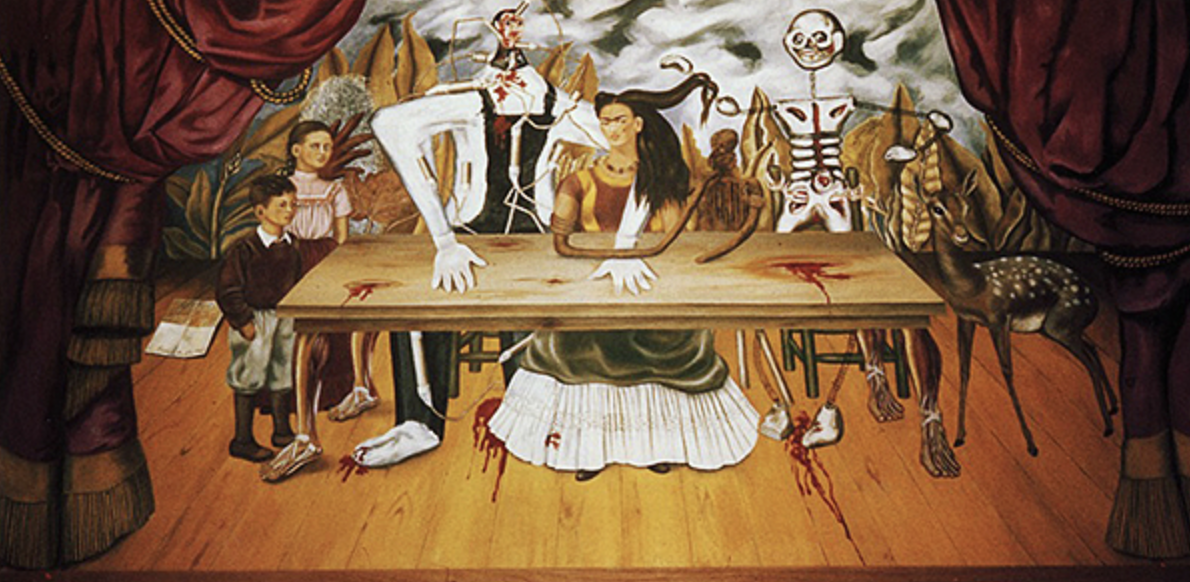

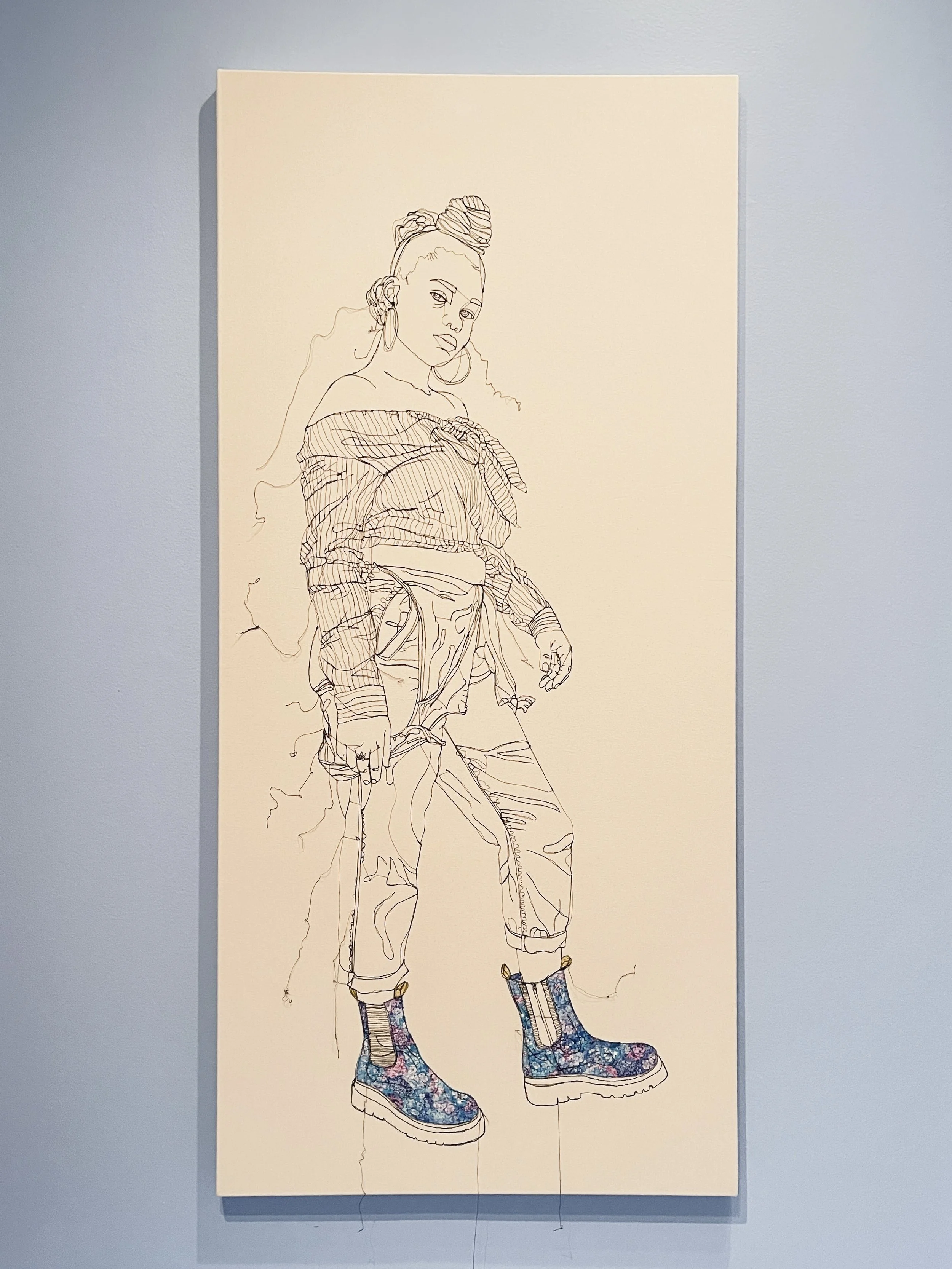

Changing Bodies, Changing Definitions: Redefining Beauty

The exhibit then pivots to “Changing Bodies, Changing Definitions, where we witness how the nude evolved in art in relation to shifting conceptions of sexuality. In the 19th century, artists often depicted ambiguously gendered adolescents — but by the early 20th century, those figures gave way to striking portraits of well-muscled men and women. Romaine Brooks’ androgynous nude of her female lover sits alongside Tamara de Lempika’s muscular female nude.

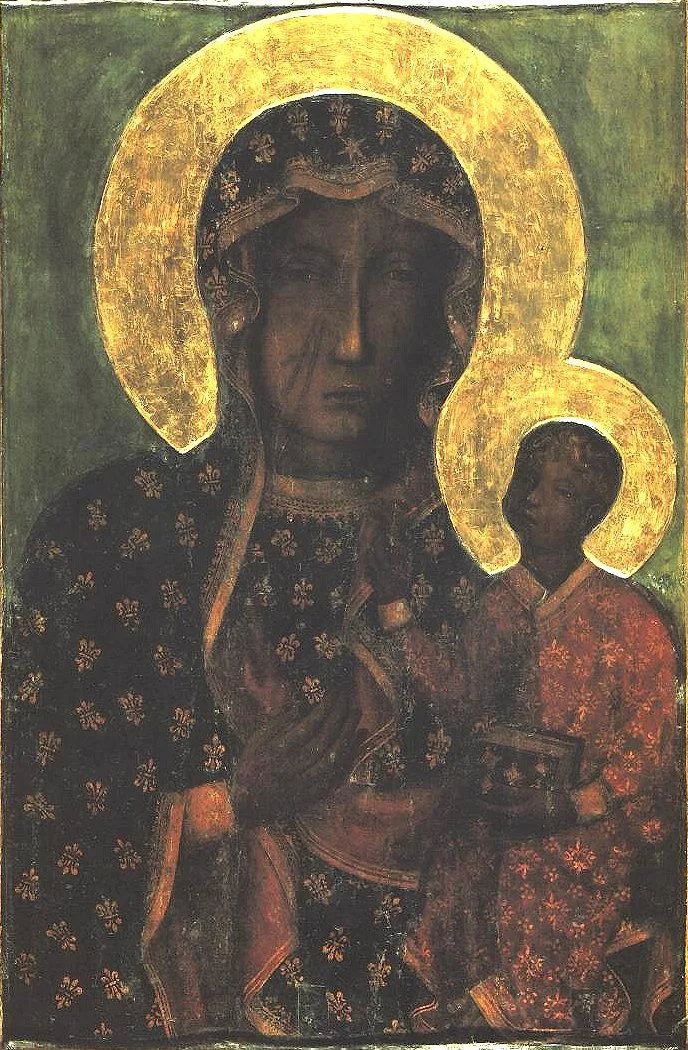

The French novelist Marcel Proust and his lover, Reynaldo Hahn, referred to Madeleine-Jeanne Lemaire as Maman, or Mother, acknowledging her centrality to queer relationships and networks. Lemaire hosted a regular salon well attended by homosexuals, including Proust, Hahn and others such as Sarah Bernhardt, whose work is also featured in this exhibition.

The close-knit queer relationships that defined Lemaire’s social circle also come through in her painting. While many of her female contemporaries avoided overt eroticism, Lemaire’s Manon’s Sleep presents a nude figure who is neither orientalized nor classicized, her sensuality left unapologetically unframed by allegory or genre.

The recently discarded clothes in the left-hand corner appear to take the shape of a female figure lounging in a chair, perhaps watching the nude woman sleep. Lemaire’s soft color palette, decadent textiles and languid figure also seem to emulate Rococo aesthetics, perhaps in a nod to the genre’s own scenes of erotic subversion.

Nackte Schiffer (Fischer) und Knaben am grünen Gestade (Naked Boatmen [Fishermen] and Boys on the Green Shore by Ludwig von Hofmann, 1900

Ludwig von Hofmann enjoyed a prominent career as a painter in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At the time, Germany — newly unified — looked to Ancient Greece as a cultural model, embracing public nudity as a sign of health, virtue and classical refinement. This free body culture (abbreviated as FKK in German) encouraged public nudity as a sign not of prurient interest, but of health and moral virtue.

Segregated from urban homosexual culture by questions of class and occupation, this image of nude boys and men, while undeniably homoerotic, works hard to de-emphasize its inherent suggestive qualities through a committed attention to labor.

Wrestlers by Thomas Eakins, 1899

Thomas Eakins, celebrated along with Winslow Homer as two of the finest 19th century American painters, here produced a study for an even bigger painting of a gymnasium featuring, among other scenes, two young men wrestling.

While depicting an actual wrestling move, the painting allows two men a moment of full-body contact that escapes inscription as homosexual. They are, moreover, curiously relaxed, even inert, in what is ostensibly a battle for dominance.

Nu Assis de Profil (Seated Nude in Profile) by Tamara de Lempicka, 1923

Tamara de Lempicka’s seated nude exists in a space of gender nonconformity, much like the artist herself. The figure’s heavily muscled body and tanned face suggest a masculine presence, perhaps shaped by outdoor labor, while the visible breast and porcelain skin point to a more traditionally feminine traits. The body is angled away from the viewer so as to heighten this sense of indeterminacy.

After moving from Poland to Paris in 1918, Lempicka gained recognition for her Art Deco portraits of glamorous, androgynous figures. Her style and subjects reflect her social circle, which included queer women like the writers Vita Sackville-West and Colette, and her own experiences as an openly bisexual woman.

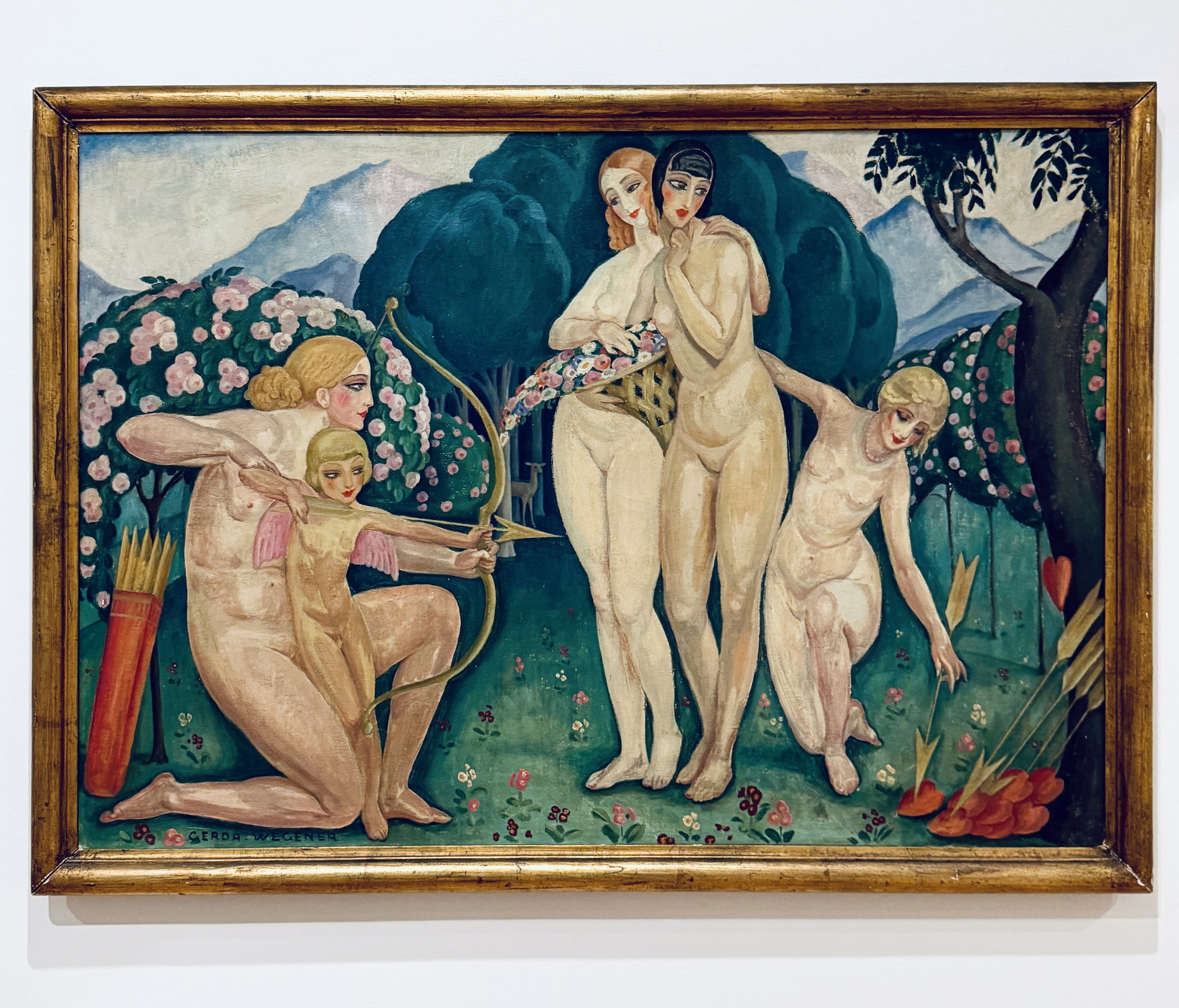

Venus and Amor by Gerda Wegener, 1920

History: Echoes of Antiquity

One of the most powerful sections, “History,” features works that portray an idealized classical past as an alibi to depict homoerotic imagery. Hans Von Marées’ Five Men in a Landscape feels suspended in a timeless queer utopia, while Rupert Bunny’s muscular Hercules takes on both dragons and sexual subtext.

Venus and Amor is Gerda Wegener’s vision of lesbian Arcadia. In her uniquely Art Deco style, Wegener depicts a garden populated by the Three Graces, Cupid and Venus, the latter helping Cupid draw his bow. Cupid is represented as distinctly nonbinary, with rosy cheeks and nascent breasts. Like the figure of Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Wegener seems to suggest Cupid’s mischievous nature is connected to his gender transgression.

When this canvas was completed, Wegener was so popular in France that the government bought three of her works for the Louvre, which are now in the Centre Pompidou collections.

Sadly, she spent her later years in poverty and died in 1940, shortly after Nazi Germany invaded Denmark.

The Joy of Effort by Robert Tait McKenzie, 1912

Robert Tait McKenzie was a Canadian physician, educator, athlete and sculptor who became director of athletics at the University of Pennsylvania. He donated hundreds of bronze homoerotic images of athletic young men to UPenn, where many are still on display.

He was a key figure in sports medicine and rehabilitative medicine, designing prosthetics for wounded soldiers. He extolled the value of exercise early, especially for those who worked primarily with their minds. Despite the undeniable homoeroticism in his work, he was married, as the norms of his time dictated.

Cumulonimbus by Kotaro Nagahara, 1909

Kotaro Nagahara (1864-1930) was one of the early innovators of yōga, or Western-style painting, in late 19th-century Japan. The relatively conservative style of his male nudes (note the lack of visible genitals) may reflect the impact of the “nude debate” (ratai ronso) in Japanese art circles in the 1890s. The influence of Western nude painting fueled an intense debate among Japanese artists about the nature of propriety and indecency, and some yoga painters like Kuroda Seiki caused controversy for displaying nude paintings to the public. In this cultural atmosphere, it’s not surprising that Nagahara took a more discreet approach here in obscuring the figure’s genitalia.

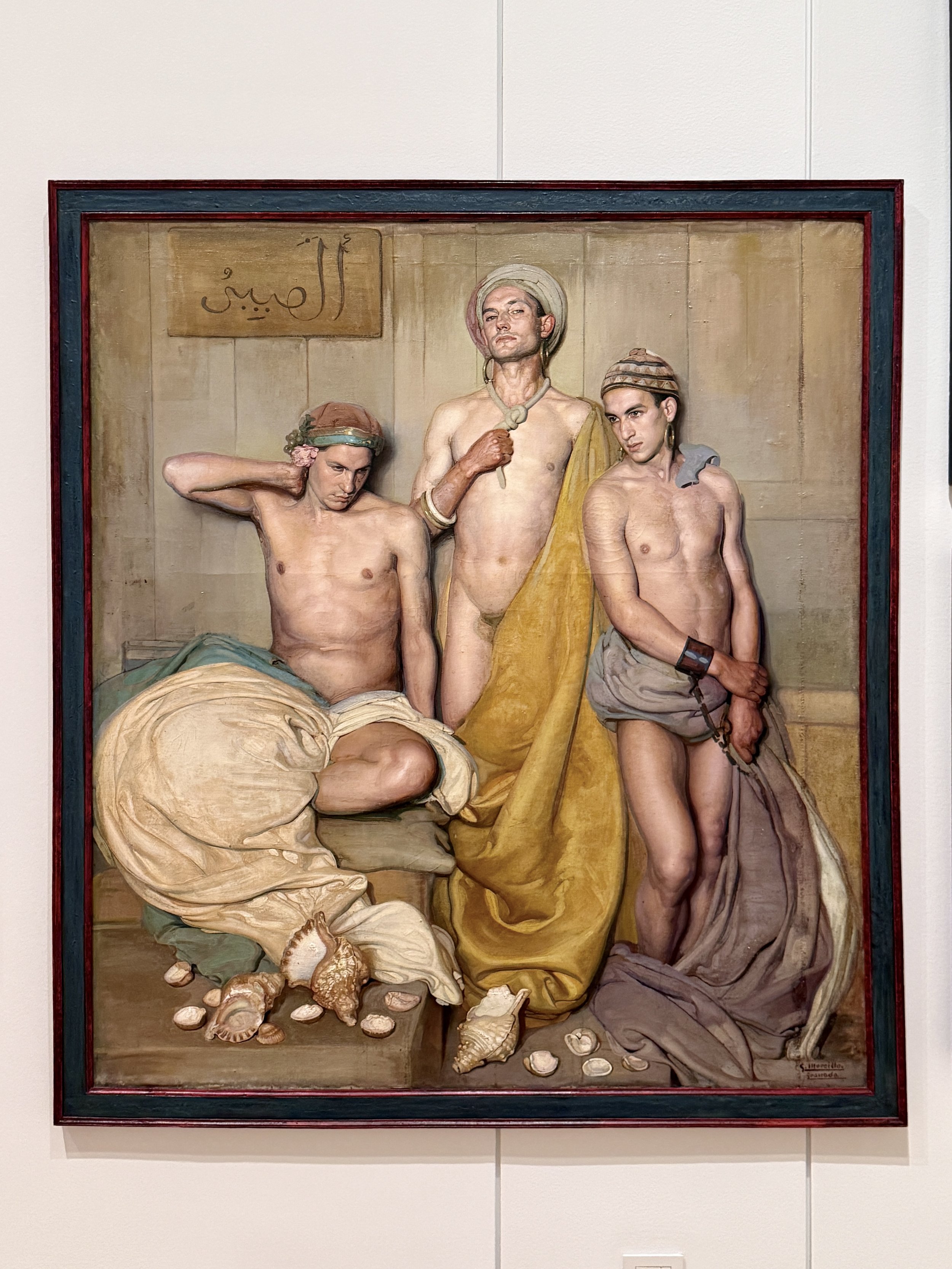

Slaves by Gabriel Morcillo, 1926

Colonialism and Resistance: Imported Shame, Native Pride

But art is never just about aesthetics. In “Colonialism and Resistance,” the exhibition explains how Western imperialism often coded queerness as foreign or degenerate, while simultaneously fetishizing it. A pernicious side effect of colonialism was that Western suppressive ideologies on homosexuality were imposed on conquered lands — many of which went from respecting same-sex relations to writing homophobic laws into their legal codes.

Gabriel Morcillo’s painting Slaves is a striking example of how Orientalist aesthetics were often used to veil overt homoeroticism. Like many artists of his era, Morcillo employed the exoticized imagery of the so-called “East” to explore themes of male beauty and sensuality, subjects that were daring and even dangerous to depict in the 1920s and early ’30s. He later experienced both the favor and the fallout of political affiliation: Between 1950 and 1955, he was commissioned by dictator Francisco Franco to paint several portraits, both standing and on horseback. With the arrival of Spain’s democratic Transition, Morcillo was classified as a Francoist, and his work largely vanished from art history books, despite its considerable artistic merit.

L’après-midi (In the Afternoon) by David Paynter, 1935

David Paynter’s In the Afternoon offers a rare and quietly radical vision of male intimacy in early 20th century South Asian art. Born in 1900 in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Paynter was known for merging Western classical techniques with South Asian subjects, often weaving subtle references to same-sex desire into his work.

In this painting, two young men share an intimate gaze, one delicately holding a flower — echoing the sensuality of Gauguin’s Polynesian women but recast through a defiantly queer lens. The image stands in quiet resistance to colonial-era moral codes that had, by that time, already begun to reshape attitudes toward sexuality across South Asia.

Before the British imposed Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code in 1861 — which criminalized “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” — many Asian cultures held more fluid and nuanced understandings of gender and sexuality. Paynter’s work gestures toward that precolonial cultural memory, reclaiming tenderness between men as both natural and beautiful.

La Danza (Dance) by Elisàr von Kupffer, 1918

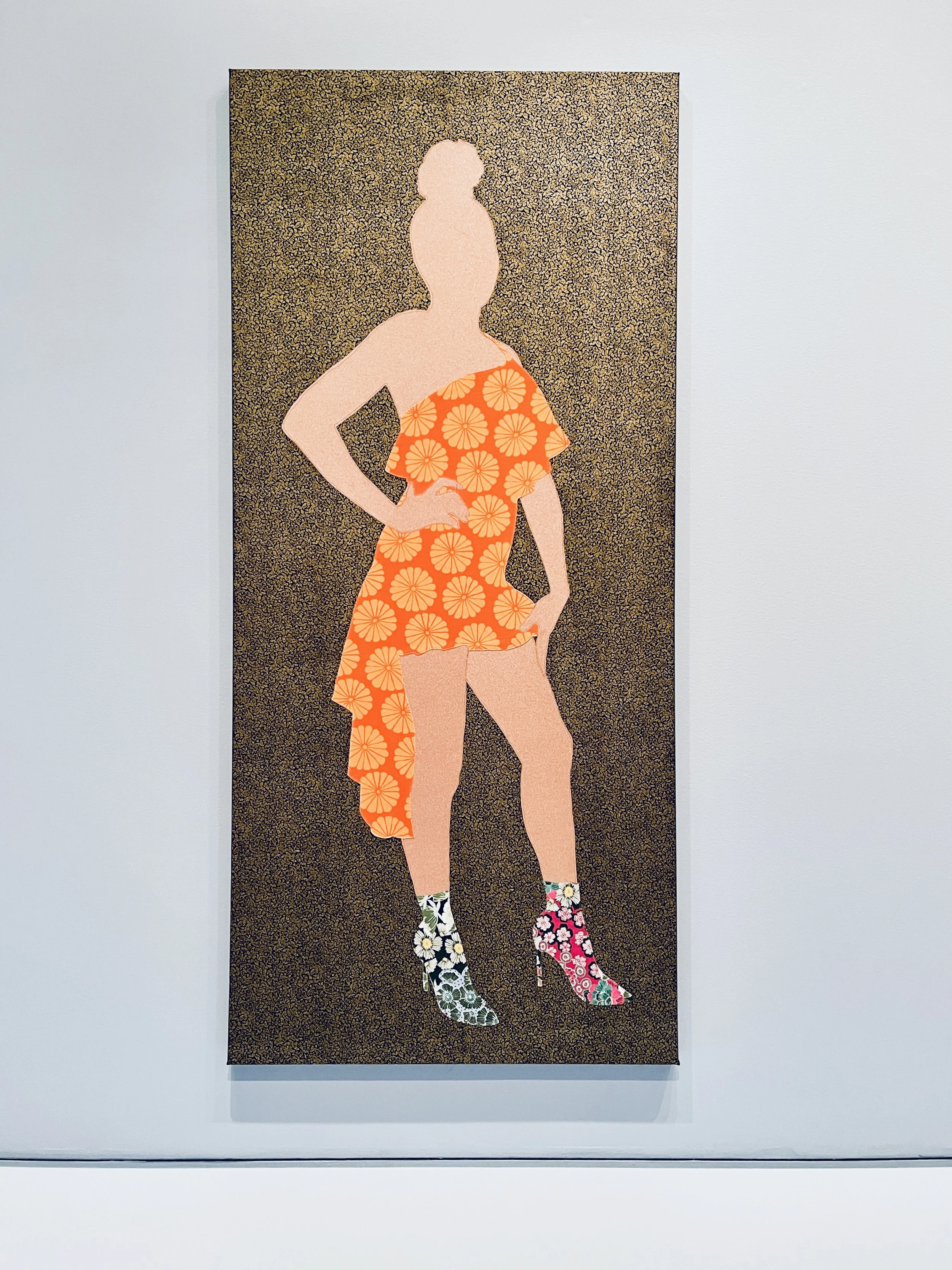

Beyond the Binary: Gender, Reimagined

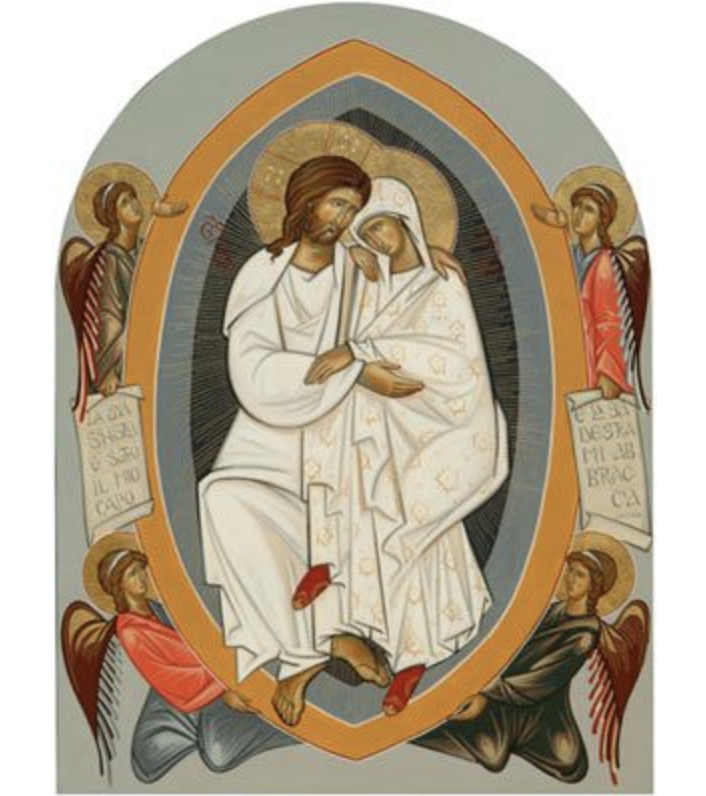

Finally, “Beyond the Binary” delivers what may be the show’s most revelatory section. Featuring more than 60 works, it draws direct connections between early queer and trans identities.

Among the highlights is one of the first self-consciously trans representations in art: Gerda Wegener’s 1929 portrait of her spouse Lili Elbe.

This section also includes paintings from the Elisarion, a utopian queer villa in Switzerland. One of these images is believed to depict the first same-sex wedding scene in art history.

Elisàr von Kupfer, who preferred to be called Elisarion, founded a spiritual movement he named Clarism, which rejected the gender binary as a perversion of divine will. Proud of his own feminine physical features, von Kupfer adorned his temple in Minusio, Switzerland, with paintings of similarly androgynous and nonbinary figures. While von Kupffer was a pioneer in challenging gender and sexual norms, he was also a white supremacist, and his work was influenced by Aryanism. He sought to engage Adolf Hitler in correspondence, though there is no evidence that the dictator ever replied.

In von Kupffer’s utopia, gender was fluid and inclusive — but race, clearly, was not. His example shows how radical views in one realm did not necessarily extend to others.

Untitled (kuchi-e [frontispiece] with artist’s seal Shisen) by Tomioka Eisen, 1895

This image was made as an illustration for the novel Sute obuna, an adaptation of the mystery novel Diavola (1885) by the British author Mary Braddon. From the 1880s onward, many European mystery stories were translated into Japanese and adapted to Japanese contexts. This could have the effect of producing unique and humorous juxtapositions between the Japanese characters and their Western mannerisms, as seen in this moment of unexpected male intimacy. Tomioka Eisen was a prolific illustrator during the Meiji Period, trained in ukiyo-e methods. He also produced a small number of erotic works, which were circulated privately.

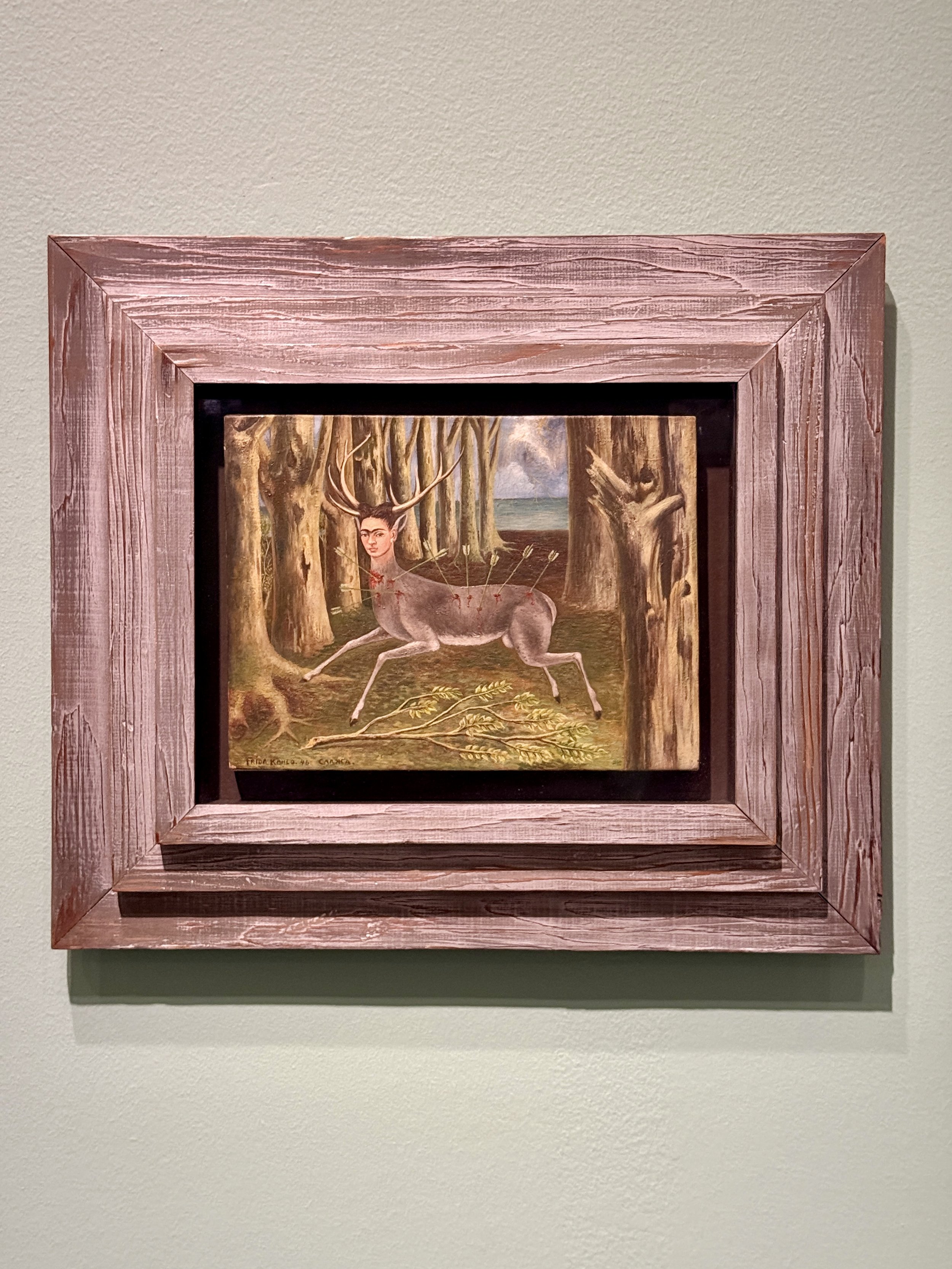

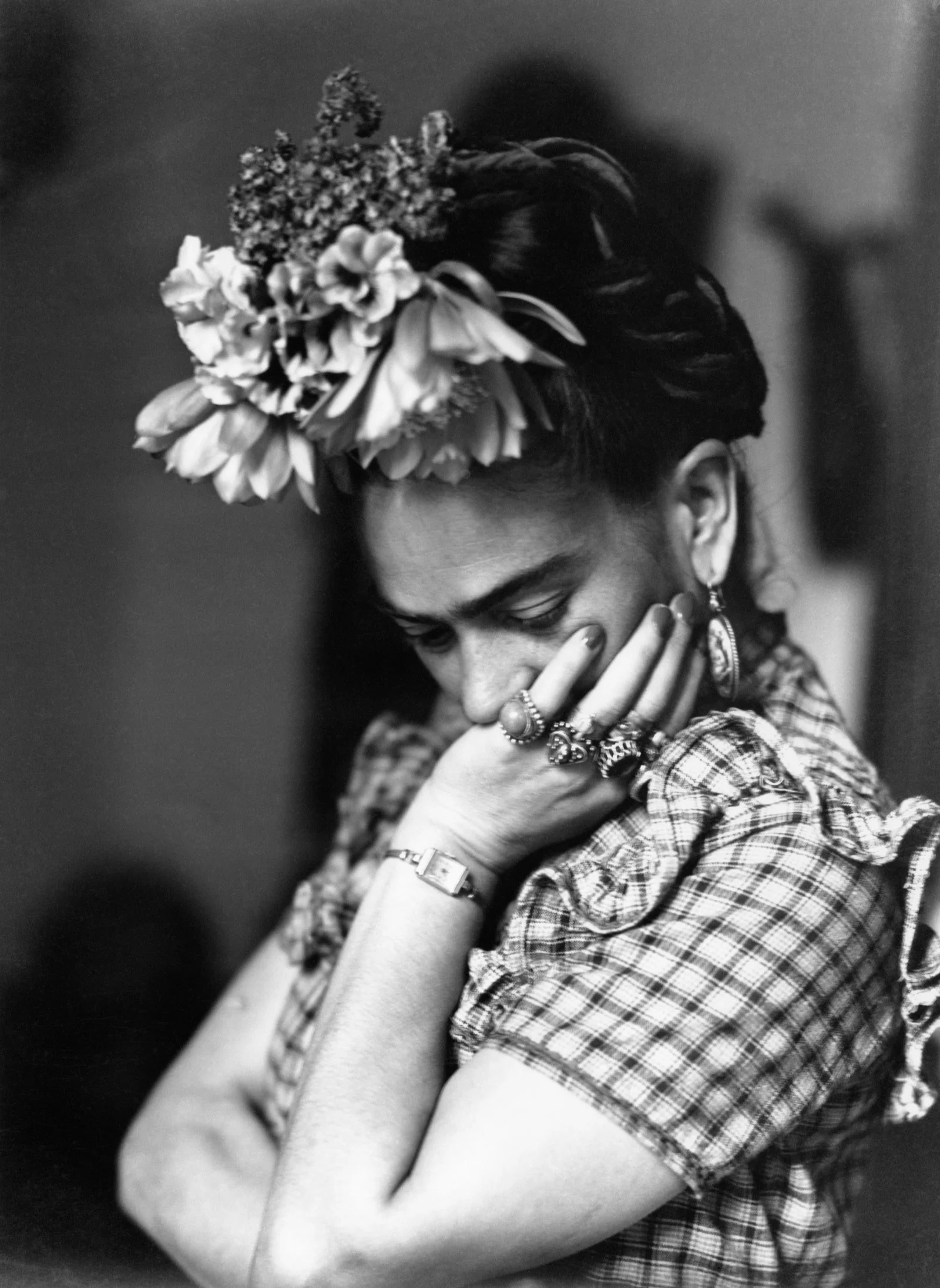

Lili med fjerkos (Lili With a Feathered Fan) by Gerda Wegener, 1920

Lili With a Feathered Fan by Gerda Wegener depicts her husband, Einar Wegener (who later became Lili Elbe), holding a green feather fan. The painting is significant as an early example of transgender representation in art, created during a period when Lili was beginning to express her gender identity more openly.

Lili first emerged in 1904 when Gerda asked Einat to pose in women’s clothing after one of her female models failed to show up. This moment marked the beginning of a public and private transformation. In the early ’20s, Lili began living more fully as a woman, and in 1930 she underwent one of the first known gender-affirming surgeries.

Their relationship inspired the 2015 film The Danish Girl. Tragically, Lili died in 1931 from complications following the final stages of her surgeries.

Peter (A Young English Girl) by Romaine Brooks, 1923

Romaine Brooks’ work from this period captures early 20th century lesbian life, with portraits of friends, lovers and fixtures of the queer world she inhabited. Here, Brooks depicts the nonbinary British artist known as Gluck, who also went by the name Peter. Gluck insisted on being addressed as “Gluck, no prefix, suffix or quotes” — rejecting any gendered association with their identity.

Amazing architecture, powerful art, dedicated docents and a relaxed, uncrowded flow make Wrightwood 659 well worth a visit.

Wrightwood 659 Does It Right

Wrightwood 659 intentionally limits the number of visitors and requires timed-entry tickets purchased in advance. This keeps exhibitions intimate and uncrowded, allowing visitors to reflect deeply without distraction.

The First Homosexuals brings together more than 300 works by 125 queer artists from 40 countries, drawn from over 100 museums and private collections around the globe. Each loaned piece contributes to a sweeping, multifaceted narrative of queer identity, resilience and creativity.

A quiet nook with a view at Wrightwood 659

Wally and I were struck not only by the scale of the exhibition, but by the obvious care with which it was assembled. Every element — from the curation of individual works to the flow of the galleries — felt deeply considered, designed to honor the artists, their histories and the communities they reflect.

We had the added privilege of visiting on a day when docents were present, enriching the experience with personal reflections and deeper context about the artists and their work. Their stories added an intimate, human layer to an already powerful presentation. –Duke

Wrightwood 659

West Wrightwood Avenue

Chicago, Illinois

USA

![Nackte Schiffer (Fischer) und Knaben am grünen Gestade (Naked Boatmen [Fishermen] and Boys on the Green Shore by Ludwig von Hofmann](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c13cc00442627a08632989/bf99309e-65ac-4776-a40b-93c658b11225/Naked+Boatmen+%5BFishermen%5D+and+Boys+on+the+Green+Shore+by+Ludwig+von+Hofmann.jpg)

![Untitled (kuchi-e [frontispiece] with artist’s seal Shisen) by Tomioka Eisen](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c13cc00442627a08632989/acfc8a3b-574b-4822-a787-aca814e59f46/Untitled+%28kuchi-e+frontispiece+by+Tomioka+Eisen.jpg)