Meet the women of the Bible who defied kings, led armies, seduced heroes, saved nations — and rewrote the rules. From Jezebel and Bathsheba to Deborah and Delilah, these are the stories of power, survival and divine disruption.

When people picture women in the Bible, they often imagine quiet obedience, gentle kindness or domestic virtue. But crack open the text, and you’ll find something far juicier: prophets, rebels, assassins, queens and seductresses. These are women who changed the course of history — whether scripture painted them as saints or sinners.

Some were praised, others demonized. Some saved lives with wisdom or loyalty. Others spilled blood without blinking. But one thing’s for sure: None of them were forgettable.

So let’s meet the fiercest women in the Bible: the faithful, the flawed and the downright fearsome.

“These women weren’t just background characters. They were prophets, plotters, protectors and provocateurs.

Some were praised. Others were punished. All of them left a mark.”

Righteous Rebels

These women broke the rules to do what was right — even when the world was stacked against them.

Shiphrah and Puah

The midwives who quietly launched a revolution

Bible Verses: Exodus 1:15–21

What They Did: When Pharaoh demanded the death of every Hebrew baby boy, these two women — likely low-status midwives — flatly refused. Instead of violence, they used wit, telling Pharaoh that Hebrew women gave birth too quickly for them to intervene. Their rebellion allowed a generation of children — including Moses — to live.

Modern Take: In a time when midwives had little social power, Shiphrah and Puah used the only weapon available: their word. Their civil disobedience predates Moses’ leadership and reminds us that revolutions often begin with women operating behind the scenes. Historically, midwives were both caretakers and quiet community leaders. Their defiance speaks to moral courage — choosing life over law in the face of a brutal regime.

Tamar

The widow who outplayed a patriarch — and won her place in history

Bible Verses: Genesis 38

What She Did: Twice widowed by the sons of Judah, Tamar was promised a third husband — but her father-in-law failed to deliver. Taking matters into her own hands, she disguised herself as a prostitute and slept with Judah. When she was found pregnant, he ordered her execution — until she produced his own staff and ring as proof of paternity. Judah, stunned, admits, “She is more righteous than I.”

Modern Take: Tamar’s actions are morally complex but deeply rooted in justice. In a system that left widows vulnerable and childless women powerless, she navigated patriarchal structures with strategy and nerve. From a historical lens, she subverted the levirate marriage laws — which stated that if a man died without children, his brother or another close male relative was expected to marry the widow — to claim her rightful place. Her story is one of resilience and survival: a woman taking back agency in a rigged game. Notably, she becomes an ancestor of King David and Jesus, canonizing her in the royal line.

Ruth

The loyal outsider who played the long game

Bible Verses: Book of Ruth

What She Did: After losing her husband, Ruth makes a bold choice: She refuses to abandon her mother-in-law, Naomi, and travels with her to Judah. To survive, she gathers leftover grain from fields — a practice called gleaning, where the poor could pick up scraps after harvest. Her loyalty and grit catch the attention of Boaz, a wealthy landowner and relative of Naomi. Ruth later approaches him at night and proposes marriage — a daring move that leads to a new beginning and places her in the lineage of King David.

Modern Take: Ruth’s story is often cast as sweet and romantic, but beneath the surface lies a tale of calculated risk and social navigation. As a Moabite, she was a foreigner and likely looked down upon. But she used cultural customs — gleaning, kinship ties, levirate marriage — to secure a future. Historically, her story challenged ideas of purity and inclusion. She represents the emotional strength of caretaking and long-term resilience.

Rahab

The outsider who brokered salvation with scarlet thread

Bible Verses: Joshua 2; Hebrews 11:31

What She Did: Rahab, a Canaanite sex worker living on the edge — literally, her home was built into Jericho’s city wall — welcomed two Israelite spies into her house and hid them under stalks of flax on her roof. When the king’s men came knocking, she coolly lied through her teeth, saying the spies had already left. Then she cut a deal: If she helped them escape, they’d spare her and her family when the Israelites conquered Canaan. Her one condition? “Tie a scarlet cord in the window” — a bright, bloody thread of survival hanging from the same place where she’d once advertised her services. And when Jericho crumbled, hers was the only household left standing.

Modern Take: Rahab embodies the cunning of marginalized people who work outside the system to survive. While labeled a prostitute, she displays diplomatic skill, foresight and shrewd negotiation. In the New Testament, Rahab is actually praised for her faith and included in Jesus’ genealogy, highlighting the Bible’s complicated relationship with female outsiders. Her courage in the face of annihilation marks her as a figure of radical faith.

The Syrophoenician Woman

The woman who changed Jesus’ mind

Bible Verses: Mark 7:24–30; Matthew 15:21–28

What She Did: A non-Jewish woman asks Jesus to heal her daughter. He rebuffs her, saying it’s not right to give the children’s bread to the dogs. She replies, “Even the dogs eat the crumbs under the table.” Jesus is impressed — and heals her daughter.

Modern Take: This exchange is one of the most shocking in the Gospels. A woman, doubly marginalized by ethnicity and gender, challenges Jesus — and wins. From a cultural standpoint, her story exposes deep prejudices of the time, including those Jesus himself inherited. It’s a moment of boundary-pushing faith, persistence and maternal desperation. Theologically, it’s a turning point that expands the scope of Jesus’s mission — and it happens because a woman insisted she mattered.

Delilah

The seductress who toppled a legend

Bible Verses: Judges 16

What She Did: The Philistine rulers knew brute force couldn’t bring Samson down. So they turned to something more dangerous: a woman with motive and access. They promised Delilah a king’s ransom if she could uncover the secret of his strength. She smiled. She agreed. Then she got to work. Night after night, she coaxed and teased, feigned frustration, and tested his love with lies of her own. “Tell me,” she whispered, as he lay tangled in her lap. And every time he fed her a false answer, she sprang the trap — watching as Philistine guards failed again and again. But she didn’t give up. Delilah was patient. She made betrayal feel like affection. Eventually, Samson cracked. He told her the truth: His hair had never been cut. It was his covenant with God. That night, he fell asleep with his head in her lap. She summoned a barber. The scissors whispered. The covenant snapped. And by morning, the man who had once torn lions apart was blind, bound, and defeated.

Modern Take: Delilah is usually cast as a cold-hearted betrayer, but we’re never told her motivations. Was it about money, survival or political loyalty? Unlike Samson, she wasn’t operating under divine direction — just practical, if dangerous, cunning. Her story is a study in how women’s power — especially when sexual or strategic — is often cast as villainous in ancient texts. She fits a familiar mold: the woman blamed for the downfall of a powerful man.

Lot’s Daughters

Survivors of Sodom with a disturbing plan

Bible Verses: Genesis 19:30–38

What They Did: After watching their city go up in flames, losing their mother in a pillar of salt, and seeing their fiancés vaporized in the rubble of Sodom, Lot’s daughters took refuge in a mountain cave with their father. There were no towns, no people, no future. Believing the world had ended, they hatched a desperate plan: get their father drunk, sleep with him, and repopulate the earth. One night at a time. One sister after the other. He never knew. Both girls became pregnant — and their sons, Moab and Ben-Ammi, would go on to found two of Israel’s most persistent rivals: the Moabites and Ammonites.

Modern Take: This story is more complex than it appears at first glance. It’s not just about taboo; it’s about fear, trauma and twisted survival instincts. Culturally, it also serves as an origin story used to discredit rival nations. But viewed psychologically, this is a trauma narrative: displaced, motherless and isolated, the daughters act in desperation. Whether you see their actions as horrifying or human, they force us to confront how messy survival can be.

Athaliah

The queen who killed for the crown

Bible Verses: 2 Kings 11; 2 Chronicles 22–23

What She Did: After her son, King Ahaziah, was assassinated, Athaliah seized power by executing the rest of the royal family — except for one hidden grandson. She ruled Judah for six years until she was overthrown by a priest-led coup.

Modern Take: Athaliah did what male monarchs often did — secured power by eliminating rivals — but as a woman, her actions were scandalous. Her rule is painted as a dark, wicked time, but she clearly held onto the throne with force and strategy. She may have been protecting her dynastic line (as the daughter or stepdaughter of Jezebel). Her reign reminds us how easily women in power are branded as unnatural or evil, especially when they don’t play “mother” or “queen” in the expected ways.

Herodias

The queen who silenced a prophet

Bible Verses: Mark 6:17–29; Matthew 14:3–11

What She Did: Herodias didn’t just marry into power — she remarried into it, divorcing Herod Philip to wed his half-brother, Herod Antipas. The move consolidated her influence but scandalized the region, and no one was louder about it than John the Baptist. He didn’t whisper, he shouted — from the riverbanks and beyond — that her marriage was unlawful. Herodias, humiliated and enraged, bided her time. That moment came during Herod’s birthday banquet. Wine flowed. Dancers twirled. Her own daughter took the floor — young, dazzling and magnetic. Herod was so pleased he promised her anything, even half his kingdom. Coached by Herodias, the girl made a simple, chilling request: “I want the head of John the Baptist — on a platter.” Moments later, the prophet’s severed head was paraded through the banquet hall like a party favor.

Modern Take: Herodias is often reduced to a manipulative villain, but she was defending her position in a fragile political marriage. John the Baptist was attacking the legitimacy of her union. In ancient honor-based societies, public shame could be fatal. While her methods were brutal, they weren’t out of place in Herodian politics. Her story underscores how women were forced to wield indirect power — often through spectacle, scandal or seduction — because direct influence wasn’t allowed.

Prophets, Leaders and Warriors

They spoke for God, commanded armies, interpreted law, or held entire kingdoms together — often in sandals, not armor.

Deborah

The prophetess who led from both the palm tree and the battlefield

Bible Verses: Judges 4–5

What She Did: Deborah was both a prophet and a judge — meaning she settled disputes, delivered divine messages, and led Israel during one of its most chaotic eras. She summoned the general Barak to battle and foretold that a woman (not him) would get the glory. Spoiler: She was right.

Modern Take: Deborah is often treated as an exception to the rule. But maybe she just proves the rules were never the point. She’s not framed as masculine or controversial; she simply leads, with wisdom and clarity. Her story challenges the idea that women in ancient Israel were always silent or sidelined. Historically, her rise may reflect periods when traditional structures collapsed and leadership was open to those with proven charisma and vision — regardless of gender.

Jael

The housewife who nailed it — literally

Bible Verses:: Judges 4–5

What She Did: After the Canaanite general Sisera fled the battlefield, he sought shelter in Jael’s tent. She welcomed him, gave him milk, waited until he slept — and then drove a tent peg through his skull.

Modern Take: Jael’s act is both shockingly violent and deeply subversive. She’s not a soldier, but her tent is her battlefield — and she uses tools from daily life (a hammer and peg) to carry out a political assassination. In ancient Bedouin culture, women often set up tents, so she used her own domestic domain as a trap. The story celebrates her action without moral panic — unusual for biblical violence involving women. She’s framed as a hero, not a murderer. Think of her as the ancient world’s quiet avenger.

Esther

The queen who played the long game and saved a nation

Bible Verses: Book of Esther

What She Did: Chosen as queen for her beauty, Esther kept her Jewish identity secret — until the king’s righthand man plotted genocide. Risking death, she approached the king without invitation and, through a series of well-timed banquets and pleas, exposed the plot and saved her people.

Modern Take: Esther is often seen as a passive beauty queen turned heroine — but she’s far more strategic than that. She uses every tool available to her in a deeply patriarchal court: silence, timing, performance and, yes, her looks. Her story reflects the vulnerability of diaspora communities under imperial rule. Esther’s courage is slow-burning but explosive. She teaches us that bravery doesn’t always look loud — and that saving lives can sometimes start with throwing a really well-planned dinner party.

Judith

The widow who prayed, seduced and beheaded her way to freedom

Bible Verses: Book of Judith (in the Apocrypha)

What She Did: With her city under siege, Judith took matters into her own hands. Dressed in her finest, she infiltrated the enemy camp, charmed the general Holofernes, got him drunk — and decapitated him in his sleep. She returned home with his head in a bag, and the enemy scattered.

Modern Take: Judith’s story is so cinematic it’s almost unbelievable — which is why many scholars see it as historical fiction or parable. Either way, she embodies a radical blend of piety and violence. She fasts and prays before taking action, but once she moves, it’s swift and irreversible. Her tale has inspired centuries of art — and fear. She’s the kind of woman whose name never got dragged through the mud because she left no room for interpretation. She was both sword and salvation.

Huldah

The prophet who interpreted a rediscovered scroll — and shaped reform

Bible Verses: 2 Kings 22:14–20; 2 Chronicles 34:22–28

What She Did: When a lost book of the law was found in the temple during King Josiah’s reign, the officials didn’t go to a priest; they went to Huldah. She read it, confirmed its authenticity, and prophesied destruction for Judah — but peace for Josiah because of his humility.

Modern Take: Huldah was a recognized religious authority at a time when prophets like Jeremiah were also active. That’s a big deal. She shows us that literate, spiritual women had real influence in ancient Judah. Her brief story reveals how women’s voices were, at times, the final word. In a world that often forgets female scholars, Huldah remains a quiet but powerful counterpoint.

Women of Wisdom and Influence

They weren’t always the ones with swords or scrolls —but they knew how to read a room, bend a situation and leave a legacy.

Abigail

The diplomat who stopped a king from bloodshed

Bible Verses: 1 Samuel 25

What She Did: Married to the boorish Nabal, Abigail intervened when David — still a rising outlaw — was about to slaughter her household in revenge. She rushed out with gifts and a speech so persuasive that David praised her wisdom, thanked her for saving him from a terrible sin, and, after Nabal died, married her.

Modern Take: Abigail is the master of de-escalation. She’s calm, strategic and fast-moving. In a culture where women’s voices were often private or domestic, she steps directly into a military crisis and changes the outcome. She represents the “wise woman” archetype: a kind of informal authority figure often embedded in households or towns. She also offers an early model of emotional intelligence and diplomacy. Also, let’s be honest: She traded up.

Bathsheba

From pawn to power behind the throne

Bible Verses: 2 Samuel 11–12; 1 Kings 1–2

What She Did: First introduced when King David saw her bathing and summoned her, Bathsheba is often framed as passive. But later, after their son Solomon is born, she secures his claim to the throne — by confronting David and collaborating with the prophet Nathan. She later becomes the queen mother.

Modern Take: Bathsheba’s story is often filtered through male guilt: David’s sin, Nathan’s rebuke. But read closely, she transforms. After enduring trauma and loss, she becomes politically astute. In ancient royal courts, the role of queen mother was often more powerful than that of the queen herself. She became one of the few women with real dynastic influence. Psychologically, Bathsheba reflects the shift from victim to strategist: someone who learns the system, survives it, and ultimately shapes it.

The Queen of Sheba

The outsider who tested Israel’s wisdom

Bible Verses: 1 Kings 10:1–13; 2 Chronicles 9

What She Did: The Queen of Sheba traveled to Jerusalem to test King Solomon with riddles, questions and wealth. She left impressed by his wisdom and court — but not before making a striking impression herself.

Modern Take: She represents global intrigue, cross-cultural exchange and intellectual power. Historically, she may have been a South Arabian or Ethiopian ruler, and her story reflects real trade networks between Israel and Africa. In some traditions, she and Solomon have a child together, starting royal lines across Africa. Her visit challenges the idea that all wisdom flows from men or from Israel. She’s the rare woman in scripture who isn’t a wife, widow or mother, but a sovereign in her own right.

Priscilla

The teacher who quietly shaped Christian theology

Bible Verses: Acts 18:24–26; Romans 16:3

What She Did: Priscilla, along with her husband, Aquila, took the eloquent preacher Apollos aside and corrected his theology — offering deeper instruction in “the way of God.” She is often listed before her husband, suggesting she may have been the more prominent teacher.

Modern Take: In the early Church, Priscilla stands out as a female intellectual. Not reduced to the common status of helper or hostess, she was a theological mentor. Her presence shows that women were deeply involved in the formation of Christian doctrine. Some scholars even suggest she may have authored parts of the New Testament (like Hebrews), though that remains debated. She represents a model of collaborative leadership and quiet authority in a male-dominated movement.

Phoebe

The deacon who carried Paul’s most important letter

Bible Verses: Romans 16:1–2

What She Did: Paul introduces Phoebe as a deacon and benefactor (or patron), and entrusts her to deliver his letter to the Church in Rome. That means she didn’t just drop it off; she likely read and explained it.

Modern Take: Phoebe’s title, diakonos, is the same word used for male deacons. She’s the first named Church leader in Romans 16, and one of the few explicitly praised for her work. She reflects a Church still forming its structures, where women had space to lead. This makes us challenge assumptions about who held knowledge and who spread it — especially given how misogynistic the Church has become.

Divine, Symbolic and Mysterious

These women act as symbols, archetypes and cosmic forces that stretch beyond history into myth, theology and metaphor.

Eve

The first woman — and the first to reach for knowledge

Bible Verses: Genesis 2–4

What She Did: Eve was formed from Adam’s side and placed in the Garden of Eden. She listened to the serpent, ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, and gave some to Adam. The result? Consciousness, shame, exile — and, for better or worse, the birth of humanity as we know it.

Modern Take: Often blamed for “the Fall,” Eve has been scapegoated for millennia. But some see her not as wicked, but curious and courageous — a seeker of wisdom. Historically, her story has justified everything from patriarchy to childbirth pain. But reread through feminist or psychological lenses, Eve becomes a symbol of autonomy, awakening, and the cost of choosing freedom over obedience. The first to question. The first to act. And the first to pay the price.

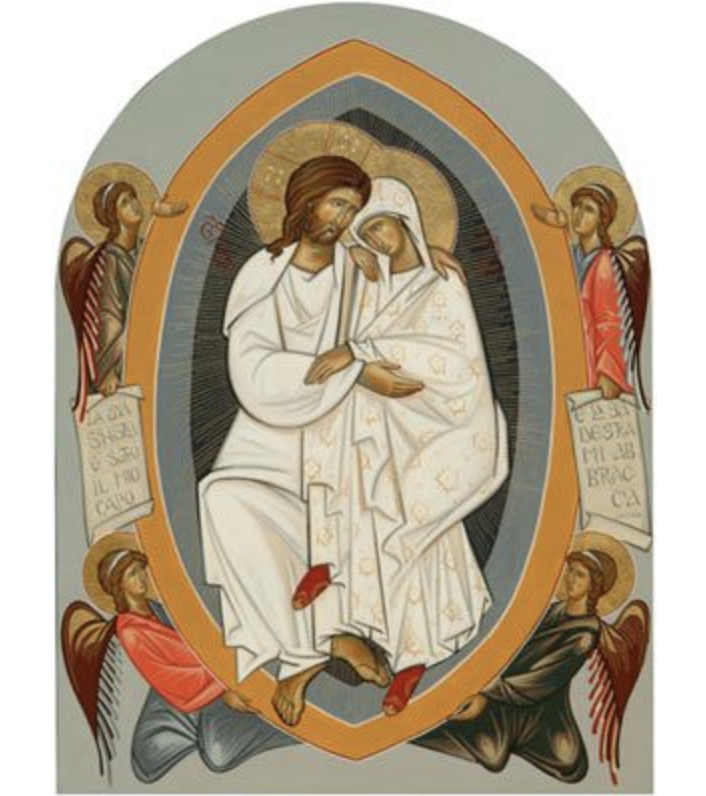

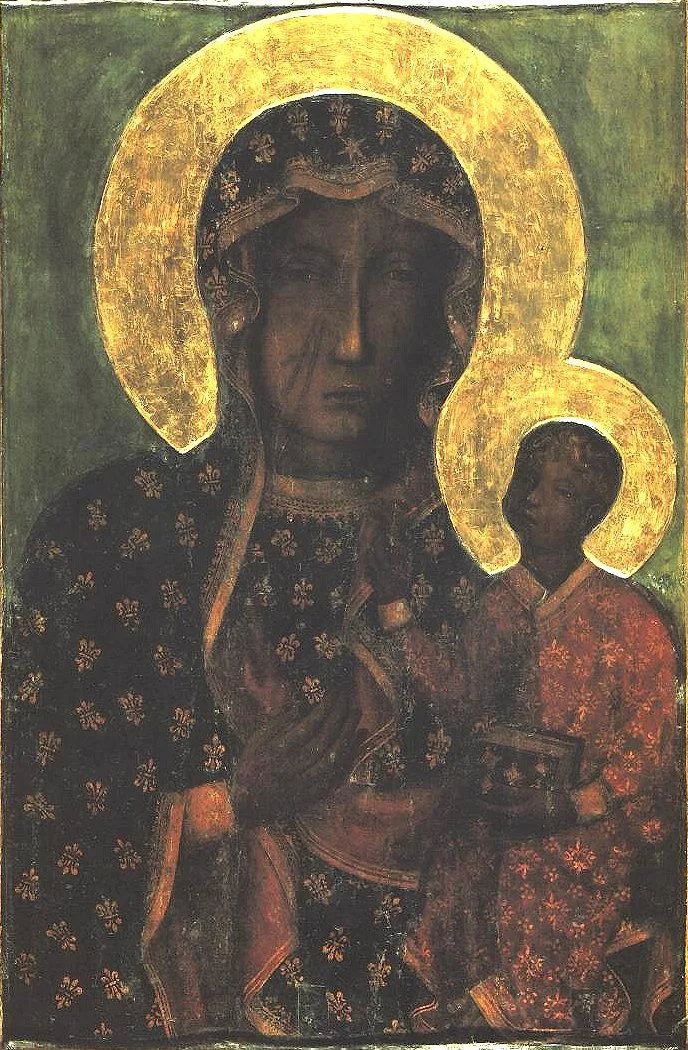

Mary, Mother of Jesus

The vessel of incarnation who sang a revolutionary song

Bible Verses: Luke 1–2; John 2; Acts 1

What She Did: Mary accepted the impossible: a miraculous pregnancy, divine purpose and certain scandal. After the angel Gabriel appeared and told her she would conceive a son by the Holy Spirit — without ever having been with a man — Mary didn’t panic, protest or faint. Instead, this young, unmarried girl in a patriarchal society said yes to a destiny that could get her shunned, divorced, or even stoned. She visited her cousin and sang the Magnificat — a bold hymn that shouted revolution. She predicted thrones would topple, the rich would go hungry, and the lowly would rise. Throughout the Gospels, the Virgin Mary stays close: from the wedding at Cana, to the cross, to the fledgling early Church.

Modern Take: Mary has long been framed as the pinnacle of passive femininity: meek and mild. But a closer reading reveals something far bolder. She’s a teenage girl who says yes to a life-threatening calling, sings a revolutionary anthem about overturning social hierarchies, and endures the trauma of watching her son executed by the state. In many cultures, she has become a mother, queen, even goddess — a figure claimed by liberation theologians, artists, mystics and mothers alike. She’s a paradox: virgin and mother, humble and exalted, human and divine vessel. Mary holds the sacred tension between idealized womanhood and radical spiritual agency. She doesn’t just bear the Word; she becomes a voice in her own right, whispering comfort, roaring justice and outlasting empires.

Mary Magdalene

The much-maligned apostle to the apostles

Bible Verses: Luke 8:1–3; John 20:1–18

What She Did: Mary Magdalene followed Jesus, supported his ministry financially, witnessed the crucifixion, and was the first to see him resurrected. Jesus called her by name — and sent her to tell the others.

Modern Take: Long confused with a prostitute (a smear introduced centuries later), Mary Magdalene was actually one of Jesus’ most loyal followers. She’s the only person mentioned in all four Gospels as witnessing the resurrection. Historically, her demotion from leader to fallen woman reflects the Church’s discomfort with powerful women. But in recent decades, she’s been reclaimed as a true apostle — equal in faith and insight. She was the first to preach the risen Christ. That’s not just symbolic. That’s canon.

RELATED: What Did Early Christians Believe?

The Woman With the Alabaster Jar

The one who poured it all out

Bible Verses: Mark 14:3–9; Luke 7:36–50; Matthew 26:6–13

What She Did: She broke an alabaster jar of expensive perfume and anointed Jesus, either on his head or feet, depending on the Gospel. Some bystanders called it wasteful. Jesus called it beautiful — and said her act would be remembered wherever the Gospel was preached.

Modern Take: This unnamed woman breaks every rule of decorum: She touches a man, pours out wealth, and interrupts a meal. But Jesus praises her more than almost anyone else in the room. Her story blends sensuality, sorrow and sacrifice. Historically, she’s been confused with other women or moralized into irrelevance. But she embodies a kind of devotion: extravagant, intuitive and unapologetic.

Wisdom (Sophia)

She who was with God before the beginning

Bible Verses: Proverbs 8–9; Sirach 24

What She Did: Wisdom is personified as a woman calling out in the streets, standing at the gates, and present at the creation of the world. She builds her own house and prepares a feast, inviting the simple to come and learn.

Modern Take: Sophia is both symbol and spirit — seen by some as a feminine aspect of God, by others as a poetic device. Her presence in Proverbs is striking: She’s active, vocal and cosmic, present at the dawn of creation. In Christian mysticism, she becomes a bridge between human reason and divine truth. For many, Sophia also offers a sacred feminine within traditions that often silence it. She echoes the ancient mother goddesses — not in open defiance of monotheism, but woven quietly into it. In this way, she becomes a goddess in disguise, allowing vestiges of female divinity to survive under the name of wisdom. Across Orthodox icons, Gnostic texts and mystical visions, she whispers of a God who speaks not only with thunder — but with intuition, mystery and grace.

The Woman Clothed With the Sun

A radiant sign of pain, power and apocalypse

Bible Verses: Revelation 12

What She Did: In a vision, John sees a woman “clothed with the sun,” crowned with stars and pregnant. As she gives birth, a dragon waits to devour the child. She escapes into the wilderness as war breaks out in heaven.

Modern Take: Interpretations vary wildly: sometimes Mary, Israel, the Church or divine femininity itself. But whatever she symbolizes, her imagery is intense. She labors while cosmic forces collide. She’s both vulnerable and protected, chased and exalted. Historically, she reflects ancient mythic tropes of the mother goddess and the serpent. Psychologically, she represents transformation: pain that brings new creation, radiance born of struggle. She’s the centerpiece of a celestial showdown.

Bible Study, but Make It Subversive

Sunday school left a lot out. It’s time to shine the spotlight on the women who flipped the script. These women weren’t just background characters. They were prophets, plotters, protectors and provocateurs. Some were praised. Others were punished. All of them left a mark.

Their stories remind us that the Bible is a wild, ancient tapestry of human ambition, courage, desperation and wit. And at the heart of that chaos? Women who dared to act.

So go ahead. Read between the (patriarchal) lines. Ask the uncomfortable questions. If you relate more to the bold, subversive, and violent women of the Bible (like Jael, who literally nailed a Canaanite general to the ground with a tent peg) than to the idealized, domestic “virtuous woman” described in Proverbs 31 — you’re not alone. –Wally