Sip, snack and stay paw-sitive! From craft brews to oceanfront views, these 4 dog-friendly spots in Hawaii — Brew’d, Oli’s, Lava Java and Appetito — welcome you and your pooch.

Picture this: You and your pup, paws in the sand, the salty breeze in your hair (or fur), soaking up that island magic. Hawaii isn’t just a paradise for sun-seekers — it’s a dog’s dream, too. From sandy beaches where tails wag freely to trails that welcome four-legged explorers, the Aloha State rolls out the red carpet for those who travel with pets.

And when it’s time to refuel? You don’t have to leave your furry best friend behind. Hawaii is home to plenty of dog-friendly restaurants where you can sip, snack and savor the moment — pup in tow. Whether you’re after craft beer, oceanfront coffee or a pizza-and-wine night, these four spots make dining with dogs in paradise a breeze. Bone appétit!

1. Brew'd Craft Pub

📍 3441 Waialae Avenue

Suite A

Honolulu, Hawaii

USA

808-732-2337

Looking for a paws-itively great pub experience in Hawaii? Brew’d Craft Pub is the ulti-mutt spot for beer lovers and their four-legged besties. With over 20 taps and more than 30 different beers, your toughest decision will be what to sip first.

Not a beer person? No worries — this spot has something for every taste, including local ciders, seltzers and a signature cocktail menu that’ll have you wagging your tail.

But let’s get one thing straight — this isn’t just a watering hole. Brew’d has a menu that goes beyond basic pub grub. Sink your teeth into fish tacos, prime rib or classic fish & chips. Veggie lovers can dig into the Szechwan cauliflower, and if you’re after a sidekick to your meal, the smoked brisket and spicy chicken sliders are top dog.

Brew’d doesn’t just tolerate pups — it rolls out the red carpet for them. The pub’s owner makes it clear on social media (and in real life): dogs are welcome! The staff is always ready to serve you and your furry plus-one, and with a spacious outdoor seating area—complete with shade and a short fence to keep things cozy — you and your pup can kick back in style.

So, if you’re sniffing around for a laid-back pub with great drinks, tasty bites, and a dog-friendly attitude, Brew’d Craft Pub is the place to be. Cheers, and give your good boy (or girl) a treat from us!

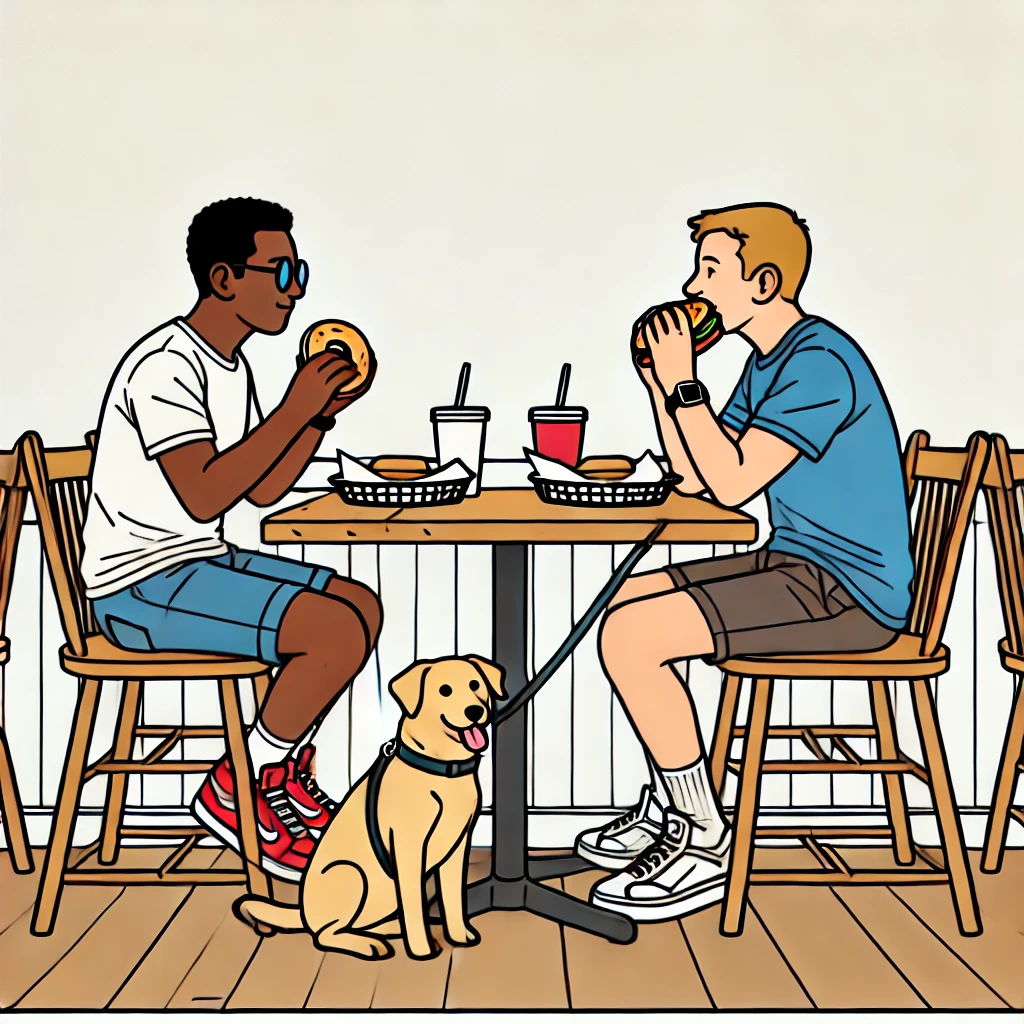

2. Oli’s Kitchen

📍 1009 University Avenue

Suite MP2

Honolulu, Hawaii

USA

808-387-0457

Looking for a spot where you and your pup can dig in without any side-eye? Oli’s Kitchen, a locally owned gem that opened in 2024, is already fetching rave reviews. Tucked near Puck Alley in the heart of Honolulu, this laidback eatery serves up local flavors that’ll have both visitors and locals drooling (hopefully just metaphorically).

Oli’s is all about fresh, island-sourced ingredients, ensuring every bite brings a real taste of Hawaii. The menu? A paws-itively delicious lineup featuring crowd favorites like breakfast burritos and the peanut butter banana stuffed French toast — because why should Elvis have all the fun?

The bright, airy interior means you won’t feel like you’re playing a game of musical chairs with your fellow diners. And yes, dogs are welcome — as long as they’re on a leash. With plenty of room to stretch out, your pup won’t have to squeeze under the table like the sneaky little snack thief they probably are.

Bonus? It’s BYOB all day, every day. Just note that a cork and ice fee may apply — because even paradise comes with fine print.

Regulars keep barking about Oli’s friendly service, relaxed vibe, and refreshingly low noise levels. Whether you’re fueling up for an adventure or winding down after a day of tail-wagging fun, this is one Honolulu hotspot you’ll want to sit and stay at.

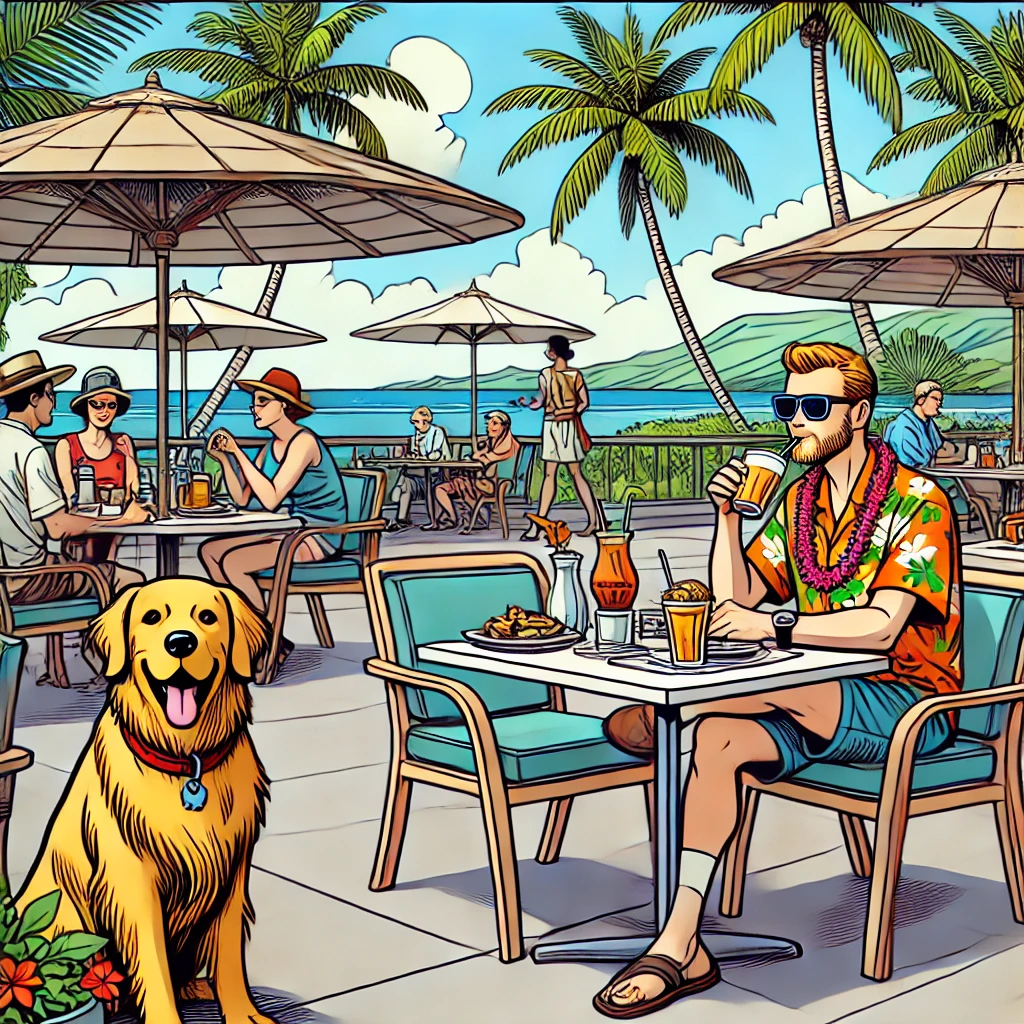

3. Island Lava Java

📍 75-5801 Ali'i Drive

Building 1

Kailua, Hawaii

USA

808-300-5672

If you’re looking for a meal with a view and a seat for your doggie, Island Lava Java in Kailua-Kona is a great choice. This family-owned, dog-friendly hotspot has built a reputation on fresh, locally sourced ingredients and a warm, welcoming atmosphere.

Start your day with their 100% estate-grown Kona coffee, paired with house-baked pastries and desserts so fresh, even your pup might be tempted to beg. The menu is packed with Hawaiian goodness, featuring free-range Big Island chicken, grass-fed beef and organic goat cheese, all sourced directly from local farmers.

The real treat? Dining on the breezy outdoor patio with its stunning ocean views. Each table comes with an umbrella for shade, so you and your four-legged friend can kick back in comfort. The staff here are paws-itively accommodating — don’t be surprised if they bring out a bowl of water for your dog before you even ask.

Whether you’re fueling up for an adventure or just looking to soak in the ocean air with your best friend by your side, Island Lava Java is a must-visit for coffee lovers, foodies and dog devotees alike.

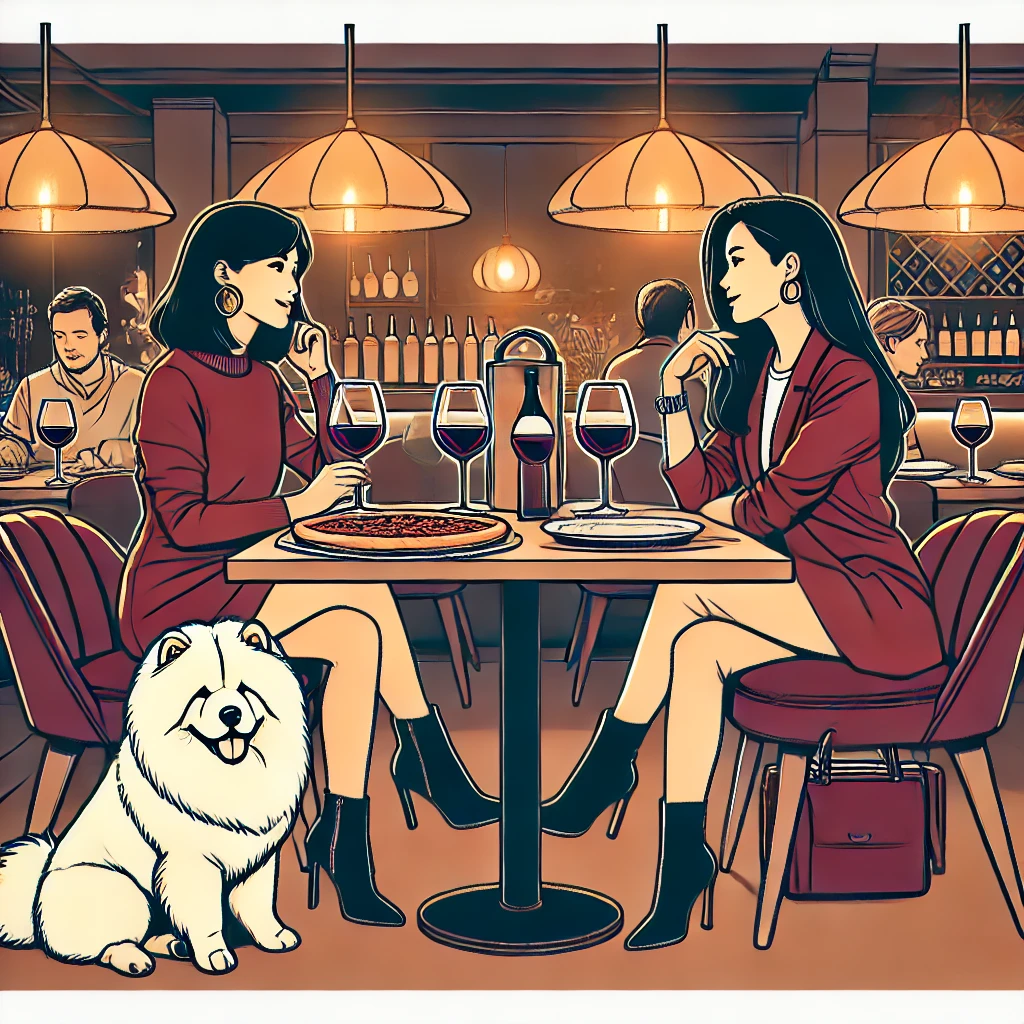

4. Appetito Craft Pizza & Wine Bar

📍 150 Kaiulani Avenue

Honolulu, Hawaii

USA

808-922-1150

Looking for a stylish night out without leaving your furry best friend behind? Appetito, located on the first floor of the Outrigger Ohana East Hotel on Kaiulani Avenue, serves up elevated Italian cuisine in a chic, laidback setting — with a dog-friendly twist.

The outdoor seating area is as impressive as the menu, making it the perfect spot for a romantic dinner, a classy night out, or just treating yourself to some top-notch pizza and pasta — all with your four-legged dining companion by your side.

Despite its casual vibe, Appetito doesn’t skimp on elegance. From the attentive service to the beautifully plated dishes, everything here is served with a touch of sophistication. The menu is stacked with crave-worthy options like Margherita pizza, steak frites with garlic sauce, spicy meatballs and Italian salami pizza — each as delicious as the next.

And if you think an upscale spot like this wouldn’t do happy hour, think again. Appetito offers a generous three-hour happy hour from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m., so you can sip on wines, cocktails and more without breaking the bank.

With free Wi-Fi, a welcoming atmosphere for kids and dogs alike, and the option to reserve your table ahead of time, Appetito is proof that you can have fine dining, fantastic drinks and a fido-friendly experience — all in one spot.

Paradise for Pups and Their People

Hawaii isn’t just a dream destination for humans — it’s a tail-wagging paradise for dogs, too. With its breezy beaches, scenic trails and dog-friendly patios, the Aloha State makes it easy to explore with your four-legged travel buddy by your side.

Of course, a well-behaved pup makes for an even smoother trip. Many visitors take advantage of Hawaii dog training services to ensure their companions stay confident and well mannered on new adventures. Programs like Sit Means Sit help dogs brush up on their skills, making everything from beach strolls to restaurant patios a breeze. Details available here.

Whether you’re hiking volcanic trails, lounging oceanside or sipping cocktails at a dog-friendly café, Hawaii offers an unforgettable experience for both you and your pooch. After all, the best adventures are the ones you can share. –Taylor Reed