Author Bettany Hughes shares surprising truths about the Great Pyramid, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and other Wonders of the Ancient World.

Quick — name the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Struggling? You’re not alone.

Most people can’t list them all. Some guess the Colosseum or Stonehenge. Others don’t realize that only one still stands.

“These weren’t just impressive buildings and sculptures.

They were bold declarations of power — a Hellenistic highlight reel that reflected the ambition and reach of Alexander the Great’s world.”

In her 2024 book The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: An Extraordinary Journey Through History’s Greatest Treasures, historian Bettany Hughes peels back the mythology and reveals the politics, poetry and propaganda behind these wonders. These weren’t just impressive buildings and sculptures. They were bold declarations of power — a kind of Hellenistic highlight reel that reflected the ambition and reach of Alexander the Great’s world.

MORE: 3 Times Alexander the Great Wasn’t So Great

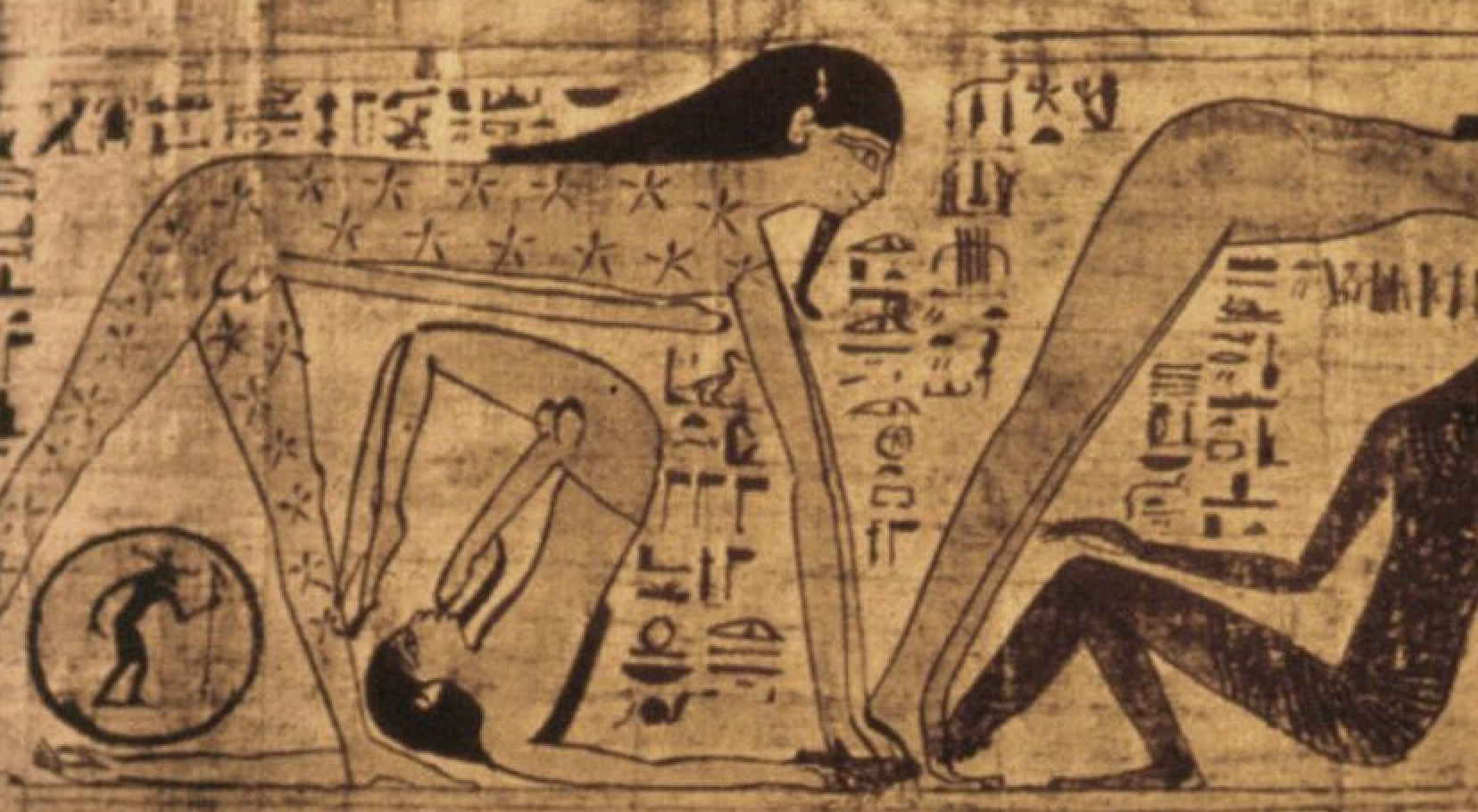

The oldest surviving version of the list was scribbled on a scrap of papyrus used to wrap a mummified body in Ancient Egypt.

Most could be visited on a single, well-planned trip through the eastern Mediterranean. This was the ancient world’s first viral travel list — and its message was clear: Look upon our works, ye mortals, and marvel.

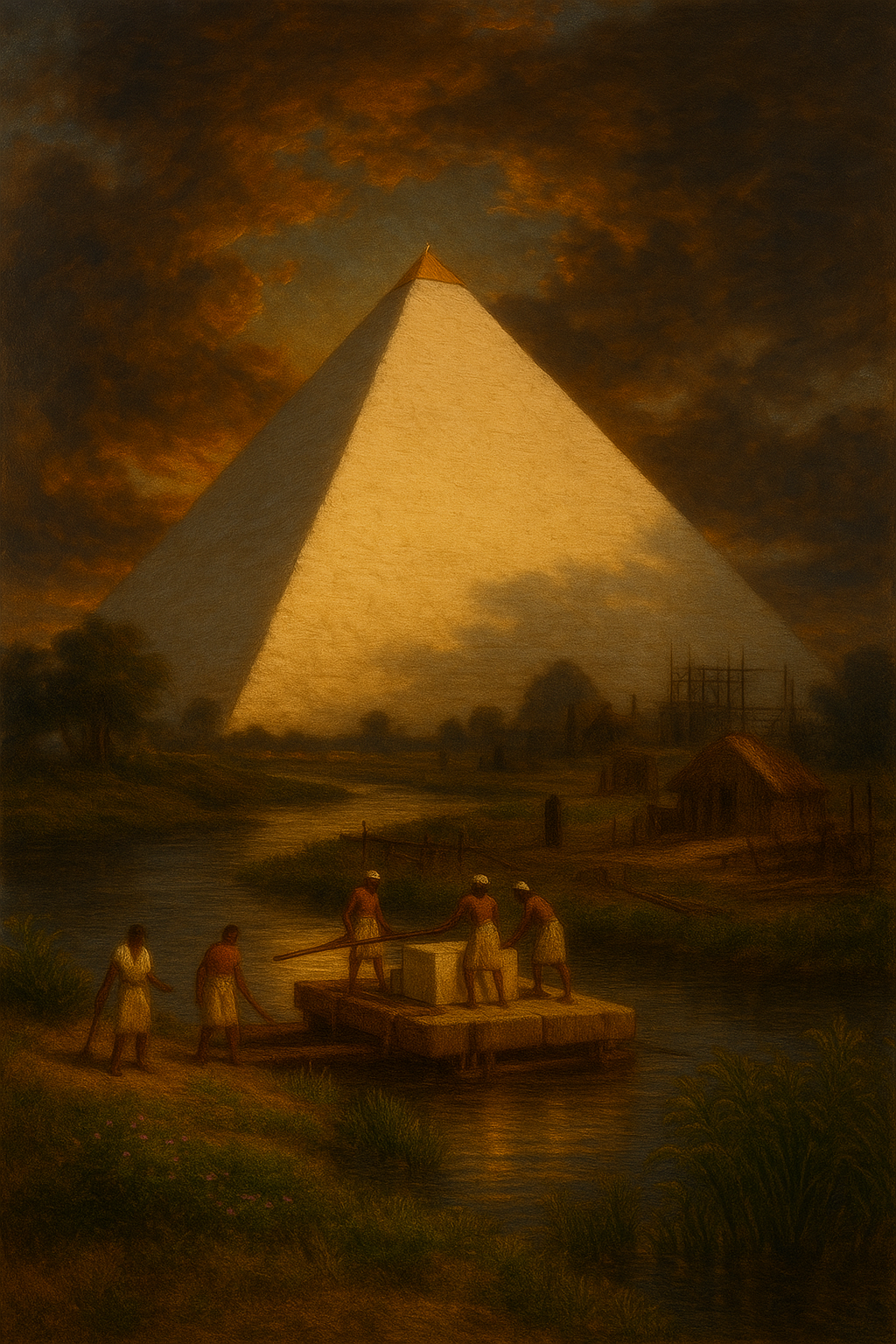

1. The Great Pyramid of Giza: A Resurrection Machine by the Nile

If you visit the Great Pyramid today, you’ll likely see a heat-blasted monument rising from a stretch of ochre desert. But what if we’ve been picturing it all wrong? Hughes urges us to reimagine the Giza Plateau not as barren but as bursting with life: “Where we see desertion, imagine an abundance of clover and thousands of homes; where there are sands, waterways; where there is emptiness, tens of thousands of workers in loincloths and linen kilts. Where there are now neutral horizons, there was once hectic color; where piles of collapsed stone, dwarf-pyramids and sloping, mudbrick mastaba tombs. Where desert, gravid green.”

Built around 2550 BCE and once faced in polished white limestone, the Great Pyramid would have shimmered with a blinding brilliance.

It wasn’t just a royal tomb; it was a “resurrection machine,” a literal launchpad to the afterlife. This machine served a higher cosmic purpose: to guarantee Egypt’s prosperity by ensuring the pharaoh’s rebirth. The fate of the world literally depended upon Khufu’s afterlife.

And the engineering behind it still leaves modern minds gasping. Standing 480 feet tall and weighing in at roughly 6.5 million tons, the pyramid used about 2.3 million blocks of limestone, each hauled into place over a quarter of a century. Its interior space alone could swallow London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, and the cathedrals of Milan and Florence — with room to spare.

Despite theories ranging from alien intervention to lost technologies, Hughes focuses on the human marvel of it all: tens of thousands of anonymous laborers working 10-hour days, 52 weeks a year, over decades — moving one block every two to three minutes. Current estimates suggest around 20,000 workers were active on the plateau at any given time, likely using a combination of sledges, rollers, ramps and perhaps even early hydraulic lifts. Still, the exact method remains elusive: “The engineering and construction of the Pyramid — the way these blocks were shaped, lifted and set in place — has confounded researchers for centuries, triggering miles’ worth of parchment and paper, and now volumes of iCloud storage,” Hughes writes. “It is a conundrum that obsesses the modern world — taxing the minds of engineers, architects, archaeologists, surveyors, even mediums.”

It’s also easy to forget that this was a riverfront wonder. In Khufu’s day, the Nile flowed much closer to Giza, hugging the Pyramid complex for most of the year, and sometimes lapping its very foundations. What we now see as isolation was once a place of movement and connection — a grand riverside attraction.

Capped with a golden or electrum pyramidion that caught the sun’s rays and hurled them back to the heavens, the Great Pyramid symbolized the original mound of creation — the divine moment when the world emerged from chaos. It was cosmic.

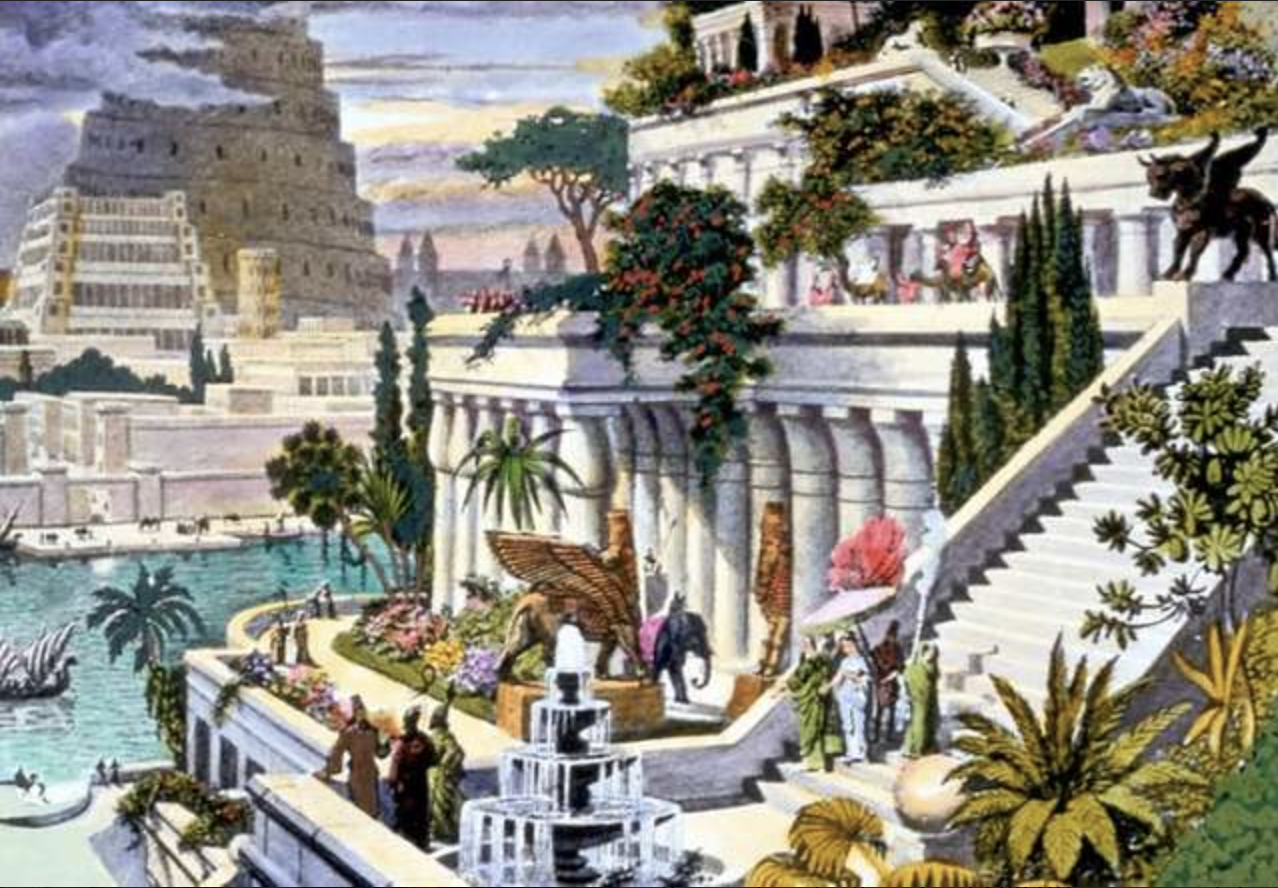

2. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon: Myth, Monument or Mistranslation?

Of all the Seven Wonders, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon remain the most mysterious — and possibly the most fictional. Unlike the Great Pyramid, whose stones still scrape the sky, the Gardens leave us with no ruins, no universally agreed-upon site, and plenty of questions. Did they even exist?

If they did, the Hanging Gardens would have bloomed sometime in the 6th century BCE, during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II — the great Babylonian king who ruled from 605 to 562 BCE and who is most often credited with their creation. That attribution, though, rests more on later tradition than contemporary evidence.

MORE: Nebuchadnezzar, King Josiah and the Formation of Jewish Law

And the evidence is where things get messy. Hughes lays out the problem clearly: Neither Herodotus nor Xenophon — Greek chroniclers who actually visited Babylon — mention the Gardens. Not once. That silence is thunderous. Even the East India House Inscription, a beautifully preserved 20-inch-wide slab chronicling the many accomplishments of Nebuchadnezzar II, makes no mention of them — no garden at all, hanging or otherwise.

So what gives?

Hughes suggests we may be looking for something too specific. What if the gardens weren’t separate from Babylon’s famed walls but were part of them — verdant terraces that flowed from the fortifications and palatial structures themselves? In many ancient lists, it’s actually Babylon’s walls that earn the “Wonder” designation, not the elusive Gardens. That ambiguity raises the possibility that what we now call the “Hanging Gardens” may have been a poetic misunderstanding — a mistranslated marvel.

And yet, the idea of the Gardens persists — not just because they would’ve been beautiful, but because they captured something deeper and darker about humanity’s emerging relationship with nature. These were not serene rooftop retreats. They were feats of engineering and control, power disguised as paradise.

“Whatever they were, however wondrous, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon would not have been idylls,” Hughes writes. “They would have been exquisite, exacting expressions of potency, expressions of belief, manifestations of ingenuity and the start of a dangerously dominating relationship with the natural world.”

Whether built in Babylon or borrowed from memories of Nineveh, the Hanging Gardens endure because they symbolize an idea: that nature could be bent into spectacle. And that idea, as Hughes suggests, has echoed through every empire since.

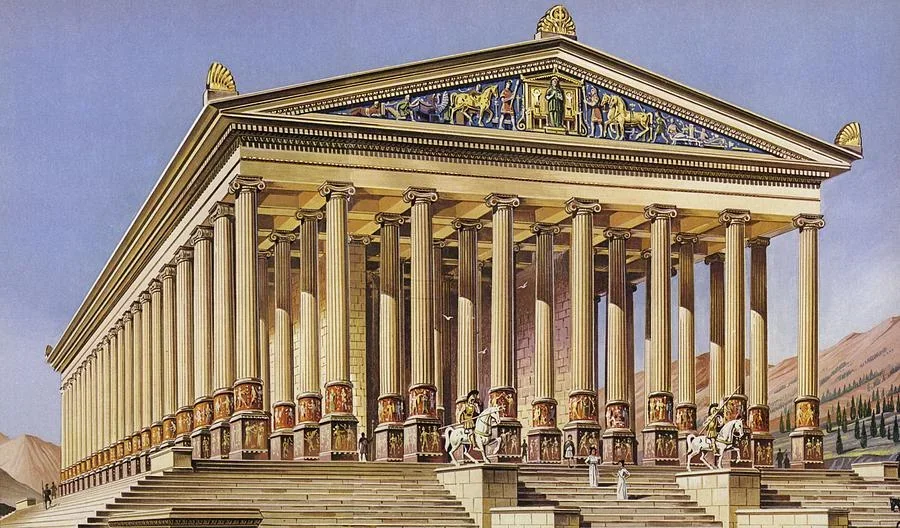

3. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus: Sanctuary of Stone and Wildness

Of all the ancient world’s architectural achievements, none left the poet Antipater of Sidon more breathless than the Temple of Artemis. Around 140 BCE, he wrote, “I have set eyes on the very wall of lofty Babylon, supporting a chariot road, and the [statue of] Zeus by the Alpheios [in Olympia], and the Hanging Gardens, and the Colossus of Helios, and the huge labor of the steep pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolos; but when I saw the temple of Artemis, reaching up to the clouds, these other marvels dimmed, they lost their brilliance, and I declared, ‘Look, apart from Olympus itself, the sun has never shone on anything that can compare to this!’”

Constructed around 550 BCE and rebuilt in grander fashion after a devastating fire in 356 BCE, the Artemision — as it was called in classical sources — was the first of the Seven Wonders to be accessible to all people, not just royalty. And it was the only one where women, both mythic and mortal, stood at the center of its story.

The original temple was incinerated on a sweltering July night — the very night Alexander the Great was born. In fact, the Greek world couldn’t help but connect the two events: “Tongues wagged: Artemis — goddess of nature and childbirth — it was whispered, was so busy in northern Greece, super-birthing a world-class megalomaniac, she neglected her earthly temple home,” Hughes writes.

MORE: Alexander the Great: 8 WTF Facts About His Early Life

The arsonist was a man named Herostratus, likely a desperate slave who torched the temple to immortalize his own name — and, ironically, succeeded. The Ephesians tried to erase him completely. Speaking his name was made a capital crime. But history, being what it is, remembered him anyway.

The rebuilt temple was a marvel: 425 feet long, 225 feet wide — nearly twice the size of the Parthenon that would follow it 150 years later. It featured 127 columns, each 60 feet high, and some capped by a skylight above the central cult statue. The structure marked the first true colonnaded Greek temple, laying the architectural blueprint for millennia to come.

Here, Artemis wasn’t the graceful huntress of Louvre sculptures. She was Asiatic Artemis, a wild guardian of beasts, bearing the mystery and fertility of the Earth. She was a goddess of contradictions — pure yet primal, distant yet intimately present.

“Artemis in the mythology of the Greeks was an unusual goddess, a female figure who stood apart from the rutting sexuality that was the norm of ancient life and myth,” Hughes writes. “The story went that on the eve of her wedding, Artemis begged her father Zeus to allow her not to marry. In most cultures at this time, women were controlled, either by having to have sex, or by not being allowed to. Artemis’s agency, and her choice, makes her attractively odd. She was a virgin, whose sphere was consummation.”

Her image, kept hidden behind a curtain in the sanctuary, was likely a wooden plank known as a xoanon — treated as a living being. It was washed in seawater, anointed in fig milk or grape juice, adorned with clothes and gold, and lovingly cared for in a process called kosmeis — the root of our word cosmetics.

The cult of Artemis was largely female-led. Young women, or parthenoi, took part in the rites. But the high priests — the megabyzoi — were eunuchs, men who had castrated themselves in service to the goddess. Their female counterparts, the melissae, were the “honey women,” underscoring the deep associations between Artemis, fertility and nature’s sweetness.

Ephesus itself had become one of the largest and busiest cities in the ancient world, its port capable of hosting over 800 ships. That accessibility helped the temple’s fame spread far and wide. It was a religious sanctuary, a political hub and — crucially — a bank. Like many temples of the time, it safeguarded vast stores of wealth and knowledge. To violate the temple was to risk divine wrath.

The mythic presence of Amazons — female warriors who were said to have founded the site — was inescapable. Their likenesses adorned the temple’s façade, doorframes and rooftop sculptures. Bronze statues of Amazons stood with short chitons, bare breasts, crescent shields and battleaxes — some even depicted with wounds.

“The Temple of Artemis is a Wonder with diverse genetic makeup and influences from both East and West within its deity, its design and its dogma,” according to Hughes. “It is a work of mankind, trying to understand the power of the natural world and the power of women.”

And Artemis herself? Her statue was encrusted with bees, lions, griffins, cows, horses and sphinxes — a tapestry of creatures and symbols. Her front was thick with mysterious swellings: ostrich eggs? Pollen sacks? Breasts? Testicles? Bags of gold? The goddess resisted definition. She contained multitudes.

Topping her cylindrical polos crown was an image of the temple itself. A shrine of power, mystery and the wild feminine, the Artemision stood as a defiant celebration of life’s most primal forces.

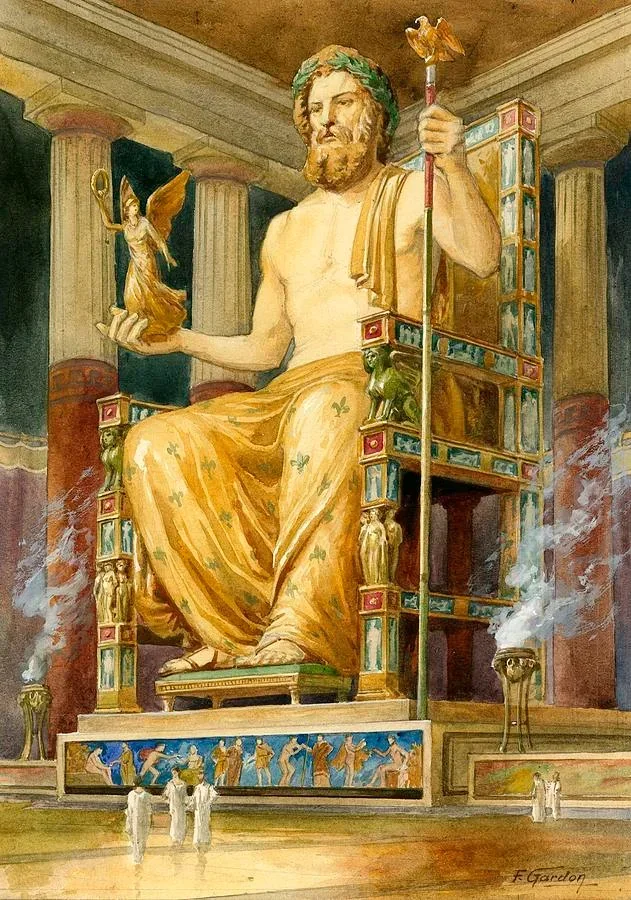

4. The Statue of Zeus at Olympia: God Made Monument

Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher, captured just how beloved the Statue of Zeus had become by the 1st century CE: “The wish to witness the ancient masterpiece of Phidias was so intense, that to die without having seen it was considered a huge misfortune,” he wrote in Discourses.

The statue of Zeus at Olympia glowed with godly gravitas inside the sanctuary’s darkened temple. A creation of the sculptor Phidias, it was a divine father made colossal: Zeus, King of the Gods, father of Artemis and Apollo, products of the rape of the titaness Leto. The statue wasn’t meant to comfort. It was meant to awe.

“Of course, in a place where men were attempting to become godlike, the ultimate god took the form of the ultimate man,” Hughes writes.

Built between 438 and 430 BCE, the statue was made of the most extravagant materials available: gleaming hippopotamus ivory for skin, gold for hair and beard, ebony, bone, polished stone and glass.

“Measuring the size of a three-story home (41 feet, on his pedestal rising over 44 feet tall), and yet seated, crouching, with his head skimming the ceiling, like Alice in Wonderland after taking her Drink Me spiked potion, the godhead must have seemed extraordinarily intimidating,” Hughes adds. “It was said that if he stood up, this Zeus would ‘unroof’ his temple-home.”

The throne featured six statues of Nike, the goddess of victory, marching up the legs. The arms of the seat were sobering sphinxes. The struts featured Herakles slaughtering Amazons to seize their queen’s girdle. The side panels showed Artemis and Apollo massacring Niobe’s children for her pride. And at Zeus’s feet? A stool supported by snarling lions — another Amazonian battlefield carved beneath.

“The message was clear: Olympia, and its Holy of Holies were, in every sense, somewhere that weakness was abhorred, for Zeus’s domain, there were only winners and losers,” Hughes explains.

In Zeus’ right hand stood a 6-and-a-half-foot statue of Nike, also made of ivory and gold. In his left: a scepter topped by a gleaming eagle. His hair curled in heavy golden locks onto his shoulders, while his ivory skin was oiled daily to prevent cracking in the damp climate. That oil pooled in a limestone basin at his feet — creating a dark twin of the god.

The temple that housed Zeus at Olympia was a masterpiece of Doric architecture, designed by Libon of Elis and completed in 456 BCE with the spoils of war. Zeus’ likeness, modeled after Homer’s verses in The Iliad, captured the very image of cosmic authority. It was said Zeus could start an earthquake just by furrowing his brow.

A wooden framework supported the ivory plating, carefully soaked in vinegar and sculpted into seamless sheets. Recent research by Kenneth Lapatin confirms the intricacy of this process — and the ingenuity of the ancients who achieved it.

When Roman Emperor Caligula ordered the statue’s decapitation in 41 CE so he could replace the god’s head with his own, Zeus reportedly laughed. The scaffolding collapsed, and days later, Caligula was assassinated — after having dreamed of the deity he sought to deface.

After standing for nearly 1,000 years, the statue was eventually moved to Constantinople, where it burned in a city-wide fire around 476 CE. Olympia’s pride, a masterpiece honored for generations, was reduced to ash.

And yet, Zeus lived on — not just in memory, but in iconography. The Byzantine depiction of Christ Pantokrator, “Ruler of All,” seated on a throne with glowering brow and commanding presence, bore a striking resemblance to Phidias’s Zeus. The divine father had been reborn.

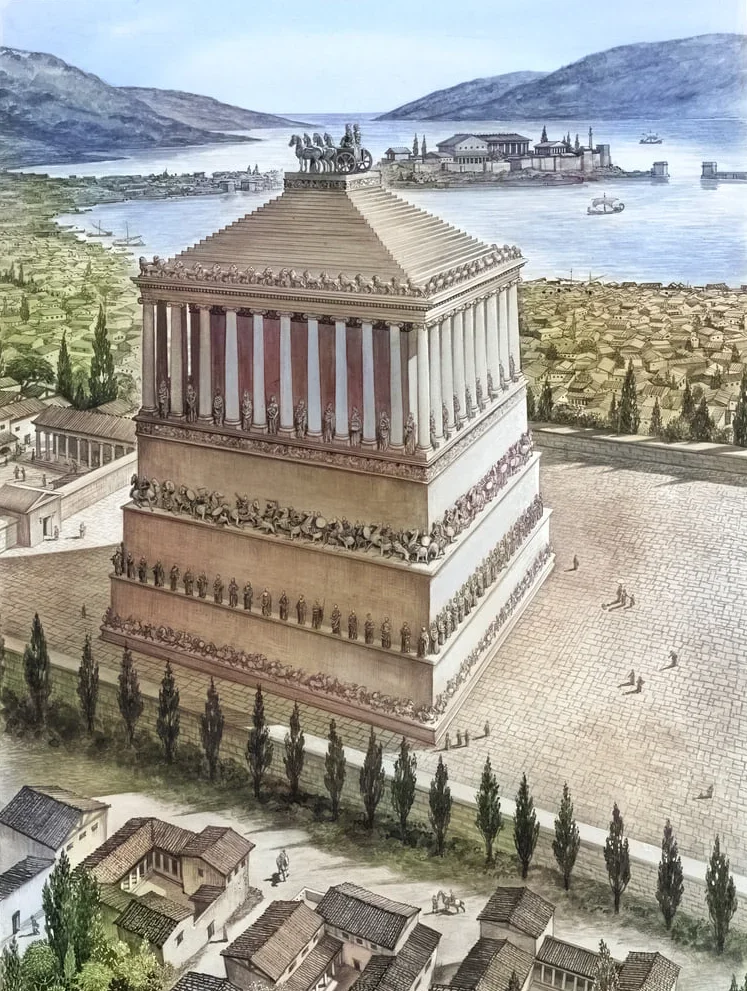

5. The Mausoleum of Halikarnassos: A Monument to Power, Grief and Glittering Excess

It was a tomb so grand it gave its name to every monumental tomb that followed. But the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos — final resting place of Mausolos, satrap-king of Karia — wasn’t just massive. It was mesmerizing. A collision of Greek elegance, Persian grandeur and Anatolian symbolism, built between 361 and 351 BCE on the sun-soaked coast of modern-day Turkey.

This Wonder fused the influences of East and West: Ionian and Doric architectural styles mingled with the dramatic scale and symmetry of Persian rock-cut tombs. Hughes notes that Karia, the region where Halikarnassos sat, was a culture of blendings — borrowing, reimagining and innovating in equal measure. And the Mausoleum was its masterpiece.

“This giant tomb came to be thought of as wonderful because it was trumpeted as embodying a faithful woman’s selfless devotion to her husband-brother, a sign that the brilliance of some men is to devastate women by dying,” she writes.

Indeed, much of its fame came from the story of Artemisia II, Mausolos’ sister and wife, who reportedly grieved so hard she mixed his ashes into her wine. But beneath the romance lay a structure of staggering ambition: a 145-foot-tall marble confection built atop a limestone terrace stretching over 785 feet — about half the height of Big Ben, and nearly the length of two football fields.

The base consisted of a rectangular podium roughly 100 by 125 feet wide. Above that, 36 columns ringed the structure, echoing the layout of the Temple of Artemis. On top of the colonnade rose a stepped pyramid of 24 tiers, leading to a grand pedestal. And at the very top? A chariot drawn by four thrashing horses, almost certainly carrying statues of Mausolos and Artemisia themselves — a couple who have been put quite literally on a pedestal.

Designed by architect-sculptor Pytheos and possibly other elite artists of the day — Scopas, Bryaxis, Leochares and Timotheus among them — the Mausoleum was both a sculpture gallery and a piece of architectural theater. Its blocks were polished to a glass-like sheen. Carvings depicted Mausolos hunting, receiving ambassadors, honoring the gods and leading battles — scenes real and imagined. Life, as Mausolos wanted it remembered, in full pageantry.

We tend to think of ancient structures as white, but many were actually a riot of color — and the Mausoleum certainly was. “Funerary monuments in particular favored color — there was a sense that the polychrome experience brought the dead back to some kind of life,” Hughes informs us. “Mausolos’ tomb would have been a firework in the sky.”

And what fireworks: white marble, then bluish limestone adorned with over 120 human and animal figures — all progressing toward a seated Mausolos before a great doorway. Was this his entrance to the afterlife? Above this level, imported white marble from Athens depicted brutal battle scenes, including — once again — Amazons, a recurring motif in Wonder architecture.

A ring of lions likely prowled the pyramid’s base. The decorative program celebrated domination, but also wildness and ritual. Priestesses in clinging, diaphanous dresses, their bodies visible beneath the folds, hint at ecstatic Bacchic rites.

Skulls unearthed at the site suggest mass animal sacrifice during the burial — a slaughter of sheep, oxen, lambs, birds. Where now there are thistles and butterflies, there were once streams of blood.

Threads of gold found among the ruins may have once wrapped the king’s cremated remains.

A spring near the site was famed in antiquity for its uncanny power to make men infertile or effeminate. That same spring inspired Ovid’s tale of the creation of Hermaphrodite: the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, lured into its waters by a nymph, merging into one being of two sexes.

The Mausoleum was a place where myth, sex, sacrifice, politics and grief all coalesced. A wonder of death, yes — but pulsing with the messy, lavish power of life.

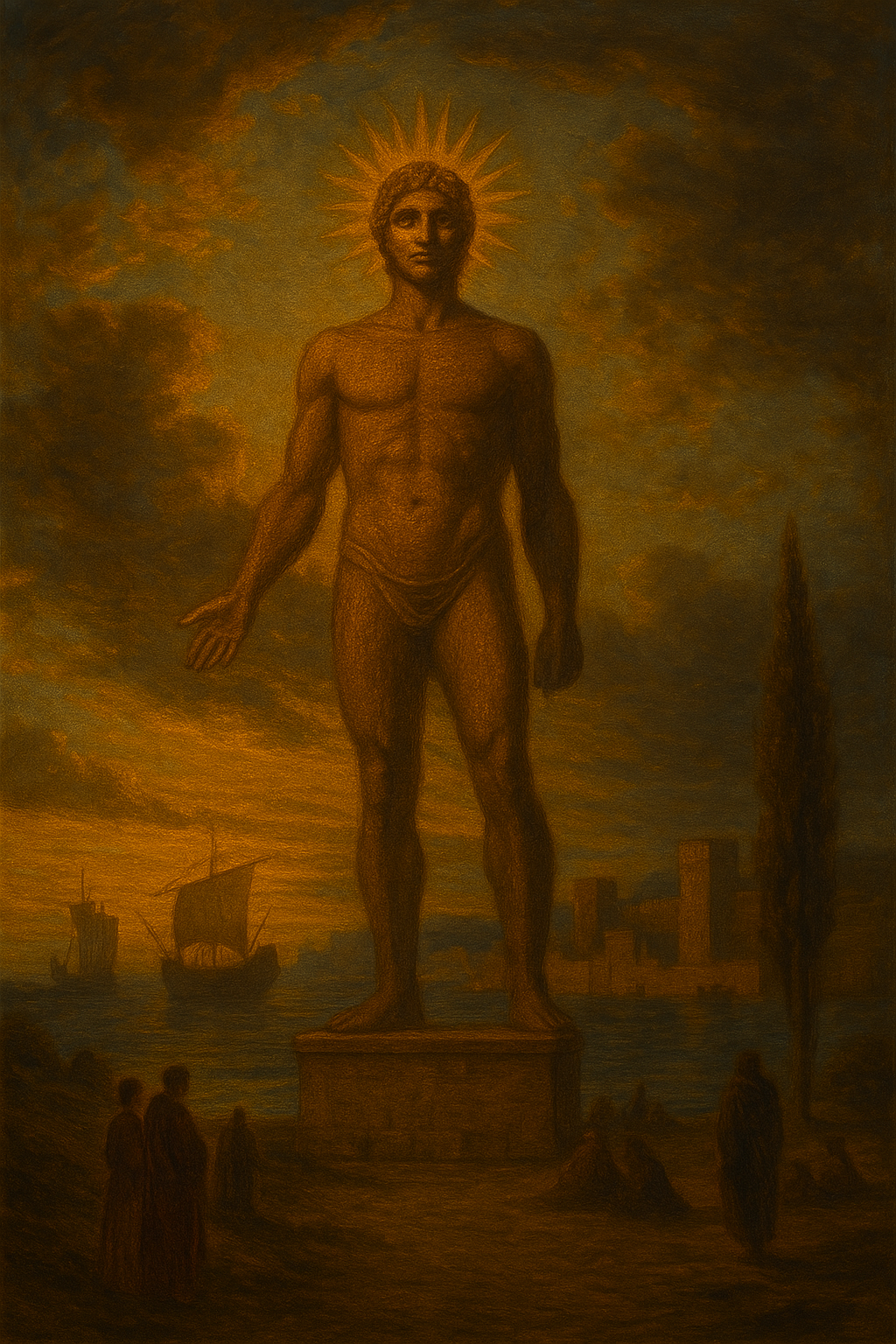

6. The Colossus of Rhodes: Bronze Giant, Fallen God

The Colossus of Rhodes is perhaps the most misunderstood Wonder. Popular imagination has long insisted it stood legs astride the harbor entrance, torch in hand, as ships passed beneath. But that towering figure, feet apart across a 390-foot waterway, is pure fantasy — a medieval myth that held the world’s imagination hostage for 800 years. (It even inspired the Titan of Braavos in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones.)

In reality, the Colossus never straddled the harbor. It likely stood higher up, on the city’s acropolis, towering above the bustling port of Rhodes. This was Helios — the pre-Olympian sun god — cast in bronze and iron, gleaming in the Aegean light.

Standing an estimated 108 feet tall, the statue was a staggering feat of ancient engineering. Built in the early 3rd century BCE and completed around 280 BCE, it had a skeleton of iron and a polished bronze skin. Just one of its digits — a single toe, say — was said to be larger than most full-sized statues.

Unlike Zeus’ patriarchal presence, Helios pulsed with youthful ambition. “Whereas the Zeus at Olympia thundered, his luxurious beard the signifier of a mature man in Greek culture, Rhodes’ Wonder, the un-bearded, tousled, soft-lipped Helios, had the dangerous energy of a young, unpredictable man poised to do great things,” Hughes writes.

And given the era, it’s hard not to see the influence and inspiration of Alexander the Great in the statue’s features and commanding pose. Rhodes had resisted a siege by one of Alexander’s successors — and the Colossus was both a victory monument and a symbol of sun-blessed resilience.

Kolossos is a Greek word — possibly of Asiatic origin — that originally meant simply “statue.” But this statue rewrote the definition. It was never just a likeness. It was legend in metal, a city’s pride forged into form.

“This was a wonder that became legendary within weeks of its completion,” Hughes says.

Created by the sculptor Chares of Lindos — and possibly influenced by the legendary Telchines, mythical inventors of metalwork — the statue took 12 years to complete. It was cast in sections, working from the feet upward. Each foot stood on a marble plinth around 60 feet wide and 10 to 15 feet thick.

And then it fell.

Around 227 BCE — just 60 or so years after it was completed — a devastating earthquake struck Rhodes. The city walls crumbled, the coastline dropped by 3 feet, and the Colossus came crashing down. It broke at the knees and was never re-erected.

The fragments, enormous and awe-inspiring, lay scattered for centuries — longer than the statue ever stood. According to later sources, the tumbled Helios remained visible until the 7th century CE, when its remains were finally melted down for scrap. So much for immortality.

And that legend has never quite gone cold.

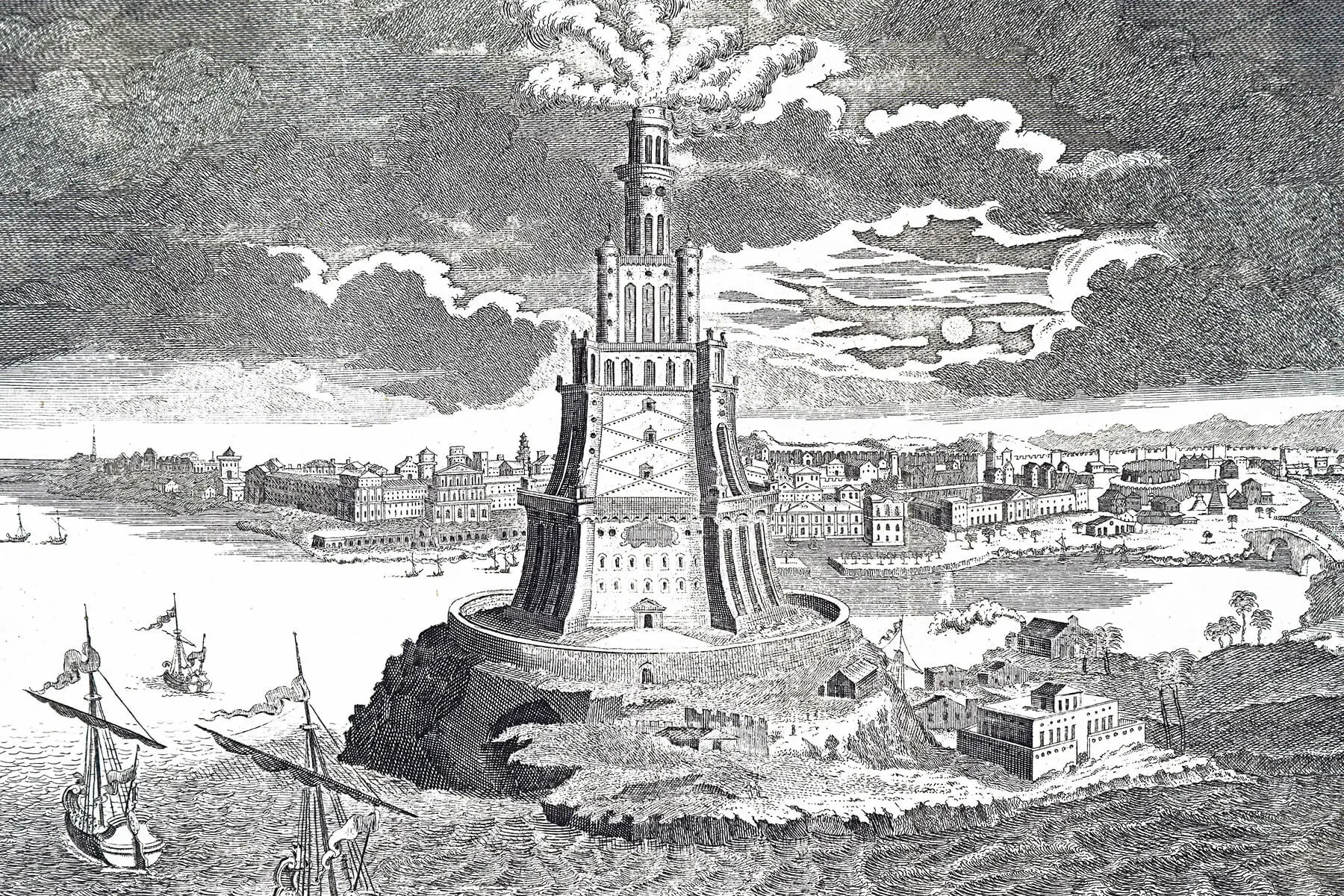

7. The Lighthouse of Alexandria: Fire, Mirrors and the Edge of the World

Unlike the short-lived Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria stood tall for over 1,500 years — a marvel of geometry, ingenuity and sheer ambition. Built beginning around 297 BCE and completed over the course of 15 years, this towering wonder rose more than 400 feet above the bustling twin harbors of Alexandria, Egypt, making it the second tallest structure in the ancient world after the Great Pyramid.

It was astonishing. A stacked sequence of geometric forms — square, octagonal, circular — constructed from marble and local limestone, sheathed in red granite shipped down the Nile from the scorched quarries of Aswan. Some blocks stretched 36 feet long and weighed 75 tons. The tower was crowned with a 50-foot statue, almost certainly of Zeus Soter (Zeus the Savior), watching over the seas like a divine lighthousekeeper.

Its beacon could be seen for over 37 miles — a flaming furnace at night, and during the day, sunlight reflected off massive copper mirrors. It was both a feat of engineering and a performance of cosmic authority. Ships approaching Alexandria’s treacherous coast — battered by crosswinds, stalked by hidden rocks — were guided by this shimmering sentinel, the Pharos.

It was built of red granite, which is usually a dull pink, but could turn an iridescent purple in desert light. “The ancients must have believed red granite brought with it some kind of sorcerer’s power,” Hughes muses.

The tower’s structure was just as beguiling: a 1,115-by-1,115-foot base with fortified brick walls and turrets; an interior ramp and hoist system to ferry fuel and supplies; and an eight-sided middle tier symbolizing the compass winds. Above that, a cylindrical chamber topped with the beacon — perhaps powered by naphtha and papyrus, possibly attended by pack animals climbing in pairs.

And the Pharos wasn’t just a lighthouse. It was also a proto-telecom tower, using flashing heliography — ancient Morse code — and possibly even mechanical sound effects. Sculpted Tritons (half-man, half-fish) stood around the structure, possibly blowing horns that served as early sirens, ancient animatronics that altered the city in times of danger.

The lighthouse was initially funded by Ptolemy I — one of Alexander the Great’s most successful generals — and completed under his son, Ptolemy II. It cost an estimated 800 silver talents — over $19 m

illion in today’s money. Built on the island of Pharos, which would lend its name to the structure and eventually become the word for “lighthouse” in multiple languages, the monument embodied Ptolemaic power and vision. It was a glowing stake in the sand, declaring Alexandria the gateway between Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean world.

And for centuries, it worked.

Until 1303 CE, when the Earth shook. An earthquake finally toppled the Pharos, reducing it to ruins and ending one of the longest-standing Wonders of the Ancient World.

Why the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Still Matter

All but one of the original Seven Wonders may be long gone — toppled by earthquakes, scavenged for scrap, or buried beneath centuries of sand and myth. But as Hughes makes clear, their true legacy is that they weren’t simply monuments to kings or gods. They were monuments to us — to human ambition, ingenuity, imagination and the drive to build something bigger than ourselves.

The list was specific, political, proudly Hellenistic — showcasing a curated world seen through Greek eyes in the wake of Alexander the Great. And yet, the idea of a Wonder has endured far beyond its original moment.

“Wonders serve a rich triple purpose,” Hughes writes. “They were constructed partly to feed our need for wondrous tales — to experience and talk about the biggest, the best, the tallest, the most strange, the most bold. They encourage a saturation in the now, by submitting to a present, pure sensation of wonder. They remind us of our overwhelming desire to collaborate to create beyond the possibilities of the individual.”

Even today, the concept of a “wonder” still fuels our storytelling, our bucket lists, our skyscrapers and our sci-fi dreams. Because deep down, we’re still looking to be amazed. Still looking to build what seems impossible. Still wondering. –Wally