Wally’s new favorite drink is a modern twist on a tiki classic, created by Chelsea Napper, bartender extraordinaire.

We just might have found you the perfect summertime cocktail: the I Feel Like a Zombie.

There’s just something so appealing about a tiki bar. All those masks and idols that are about as spooky as something out of a Scooby-Doo cartoon. The kooky glasses shaped like skulls or grimacing, bug-eyed faces. Those superstrong, fruity drinks that will knock you on your ass — some of which get set on fire! And, of course, the brightly colored garnishes, including cocktail umbrellas and bananas carved to look like dolphins.

So when you’re stuck at home (perhaps in the midst of a global pandemic) and the sun is shining and all vacations are canceled and you’re yearning for a bit of the tropics, consider whipping up a batch of I Feel Like a Zombies.

Such was the case when we ordered a delicious tasting menu from Mr. Oiishi, a takeout and delivery concept launched during the coronavirus quarantine, where various chefs create their take on Asian comfort food.

When we saw cocktail kits dreamed up by Chelsea Napper, bar director at Yugen in Chicago’s oh-so-trendy Randolph Street Corridor, we had to try one out.

Napper says she came up with the drink by “thinking about the flavors of the classic zombie tiki cocktail but much more modern.”

Which got me thinking: What exactly is the drink version of a zombie, and where did it originate?

Heavy on the rum, with just the right amount of pineapple and grapefruit, chances are you’ll feel like a I Feel Like a Zombie again soon.

The History of the Zombie Cocktail

The first imbibable zombie was created by the appropriately named Donn Beach, the patron saint of tiki bars. He was so worried about someone stealing his recipe that he went to great lengths to keep the ingredients a secret — even from his own bartenders. The recipe, from 1934, consisted only of code numbers that corresponded to otherwise unlabeled bottles on his bar. Although many have tried to hunt down the exact recipe, there’s a good chance it has been lost to the ages (though Beachbum Berry has made it a lifelong quest to uncover the secret formula — and just might have succeeded).

Beach is said to have referred to the zombie as “a mender of broken dreams” — and one so potent he wouldn’t serve more than two to a customer.

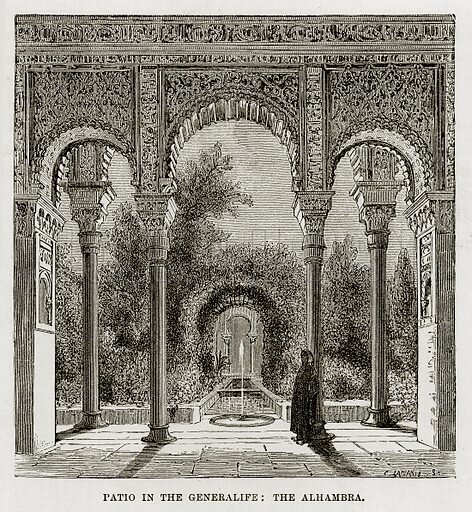

Everything you need to make this twist on the tiki classic, the zombie, including shrub and syrup.

I Feel Like a Zombie Recipe

Ingredients

1 ounce dark rum

1 ounce light rum

1 ounce pineapple cinnamon shrub

1 ounce grapefruit syrup

1 slice dehydrated grapefruit

“I recommend a light and dark rum for this cocktail, but if you’ve only got one or the other, that totally works,” Napper says.

Duke did some research and landed on Diplomático Reserva Exclusiva for dark rum and Plantation 3 Stars for light rum, which we picked up at our friendly neighborhood liquor store, Foremost in Uptown.

What the Heck’s a Shrub?

I had never heard of shrubs before. They’re also known by the unappetizing designation of “vinegar cordial.” The last time I knowingly drank vinegar was during a halfhearted attempt to pass a drug test for a summer job I didn’t want.

Shrubs are nonalcoholic syrups made of concentrated fruit, aromatics, sugar and, yes, vinegar.

Why are they called shrubs? Turns out the name is derived from the Arabic word sharab, meaning “to drink.” Shrubs were all the rage in Colonial America, when they were a tasty way to preserve fruit. Their popularity died out with the introduction of factory foods and home refrigerators but have resurged during the mixology revolution and rise of cocktail bars that like to have at least half of the ingredients in their $15 drinks be of obscure origin.

Here’s a pineapple shrub recipe to try. And a general guide to making shrubs, stating that they typically follow a 1:1:1 ratio of fruit, sugar and vinegar.

Grapefruit Simple Syrup

As a big fan of sangria and old fashioneds, I’m familiar with simple syrup. This is essentially sugar water, so there’s no denying tiki drinks are on the sweet side — though it’s offset by the high amount of alcohol and the tartness of the vinegar.

Try this recipe for grapefruit syrup.

Preparation

Once you’ve got everything you need, add the shrub and syrup to a cocktail shaker. Then add in the rum.

Fill the shaker 3/4 of the way with ice and give it a good shake for about 10 seconds.

Strain and serve over fresh ice.

Garnish with a cocktail umbrella and dried grapefruit slice if you’re feeling fancy. Bonus points for serving in tiki glasses! –Wally