A repurposed mosque, a connection to Hearst Castle, Virgin Mary processional statues and rooftop views in Ronda, Spain.

The unassuming façade of Santa María la Mayor reflects the adjacent Ayuntamiento (City Hall) and a Moorish minaret-turned-bell-tower.

After enjoying a late lunch in Ronda, Spain, on the terrace at Don Miguel, the restaurant of the hotel with the same name, we agreed to visit the Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor (Church of Saint Mary the Great). Wally and I were traveling with our friends Jo and José and were delighted to have them as our local guides for the weekend.

The food was good, but the view overlooking the steep El Tajo gorge and Puente Nuevo bridge was even better. The limestone cliffs plunge 390 feet (120 meters) to the Guadalevín River below the bridge connecting the historic old town (La Ciudad) to its modern counterpart (El Mercadillo).

“Architect Julia Morgan used the bell tower of Santa María la Mayor as the model for the ones at Hearst Castle, the estate of publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst in San Simeon, California.”

Ronda’s iconic Puente Nuevo, or New Bridge, certainly isn’t “new” — having been completed in 1793 — but it is the most photographed.

As we navigated the cobblestone streets and approached the church, we paused to gaze up at its unusual double-galleried façade, which looks more municipal than religious. The balconies were added during the reign of Felipe II and were a privileged place for nobility to watch the equestrian tournaments held in the square.

José told us that the American architect Julia Morgan used the bell tower of Santa María la Mayor as the model for the pair at Casa Grande, the main house of Hearst Castle, the elaborate hilltop estate of publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst in San Simeon, California.

Ronda didn’t just leave a mark on Hearst; it also captivated Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles, both passionate bullfighting enthusiasts who found refuge here. Welles even chose to have his ashes interred in a dry well on the Recreo San Cayetano estate of his good friend, the matador Antonio Ordóñez, on the outskirts of Ronda.

A copy of the gorgeous illuminated Libro de Horas de la Reina Isabel (Queen Isabella’s Book of Hours). For some reason, the original is at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Sacred Transformation: The Evolution of Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor

The church used Ronda’s principal mosque as its foundation. But long before that, the site was allegedly a Roman temple to Diana, goddess of the hunt.

The conversion from mosque to church began in earnest following the Reconquista of Ronda by Christian military forces in 1485. By the following year, King Fernando II (1479-1516) reconsecrated it as an abbey dedicated to the Virgin of Encarnación.

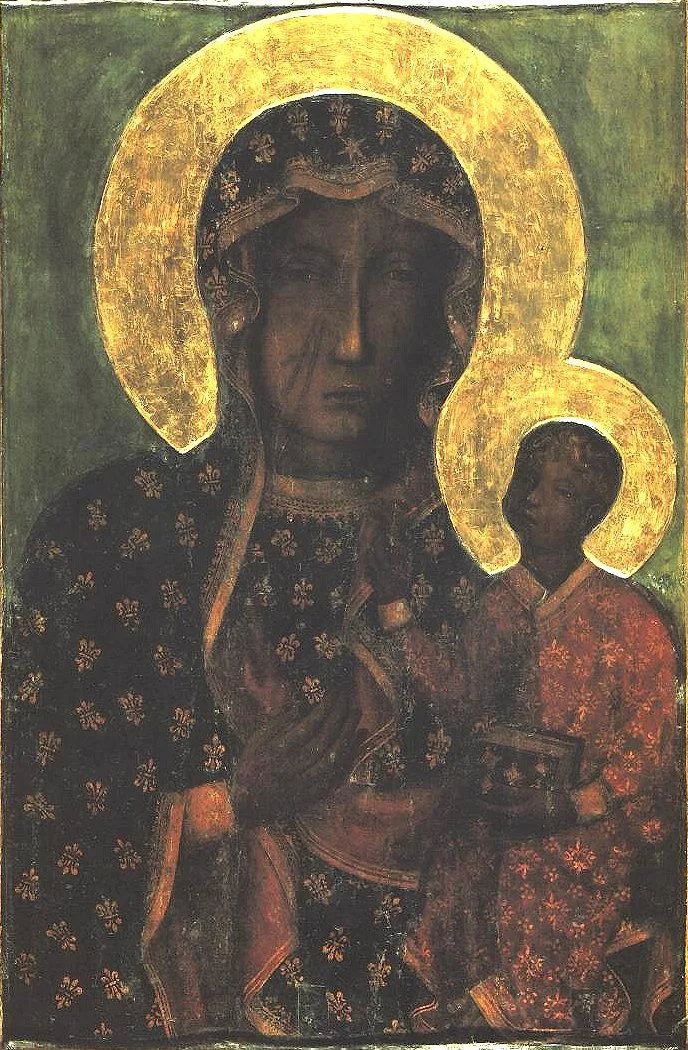

A statue of Mary as the Queen of Heaven. One interpretation of the crescent moon she’s standing on is that it represents her perpetual virginity.

During the reign of Charles I (1519-1556), its status was elevated to “colegiata” — a collegiate church — led by a clergy of ordained ministers without the direct involvement of a bishop. Its official title is the Real Colegiata de Santa María de la Encarnación la Mayor de Ronda, but locals commonly refer to it as the Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor due to its 19th-century designation as a “high parish” or “parroquia mayor.” Mass is held on Sundays and public holidays at 1 p.m. and on Thursdays at 8 p.m. April through September.

Traces of its Islamic past are evident in the square-shaped body and arched windows punctuating the bell tower’s brick exterior, which originally served as the minaret of the mosque. It was probably more cost-effective to appropriate and reuse than to completely rebuild. Even so, the renovation of Santa María la Mayor required substantial funding and took nearly two centuries to complete.

The remains of the mihrab, a semicircular prayer niche covered with stylized Arabic calligraphy and indicating the direction of Mecca, is visible from within the vestibule. Beyond is the gift shop, where we purchased admission for 4.50€ or about $5 per person to gain entry.

This three-tiered chandelier suspended from the central vault of the Renaissance nave includes 34 lights and 24,700 pieces of sparkling cut crystal.

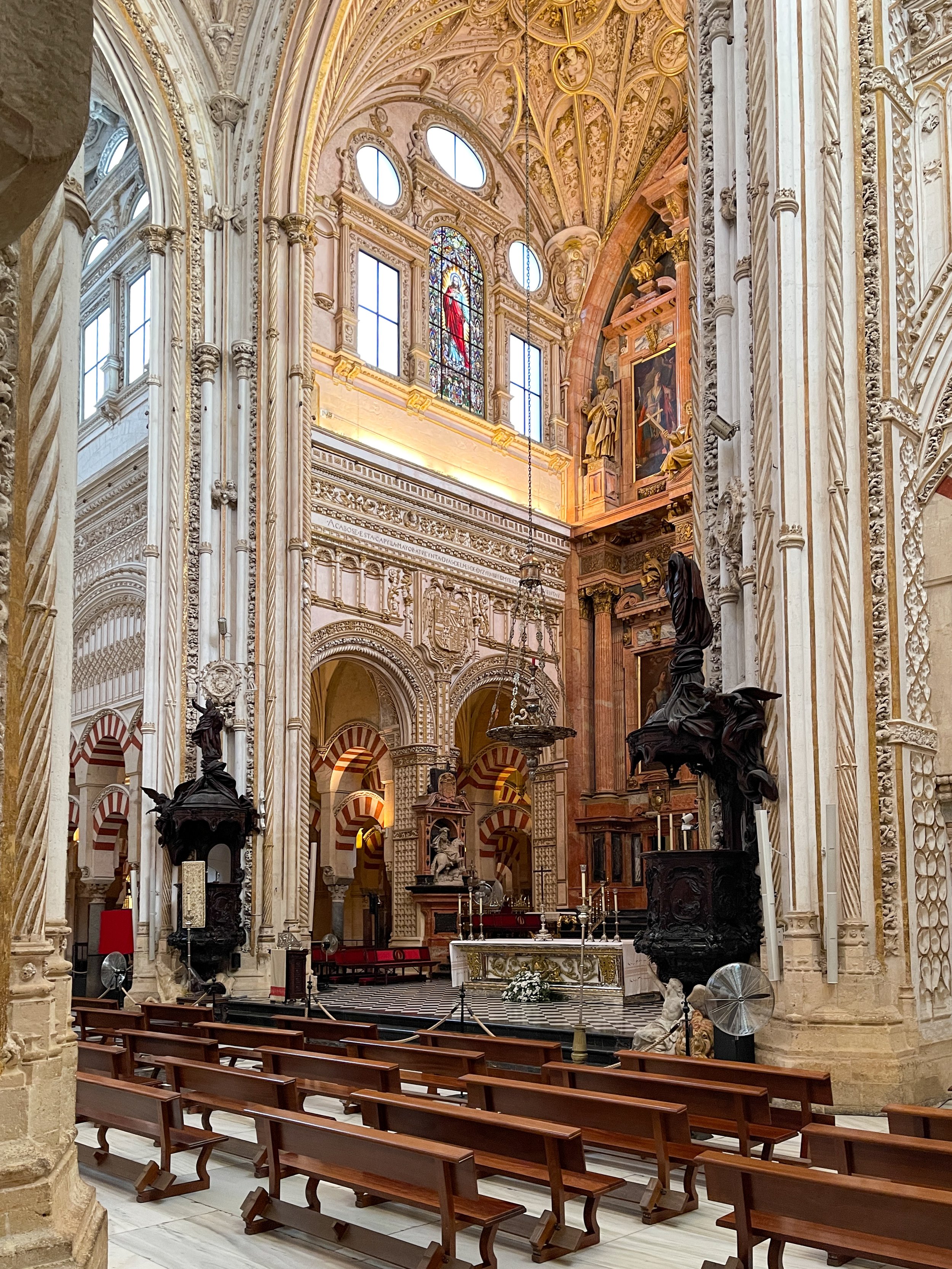

Split Personality: The Interior of Santa María la Mayor

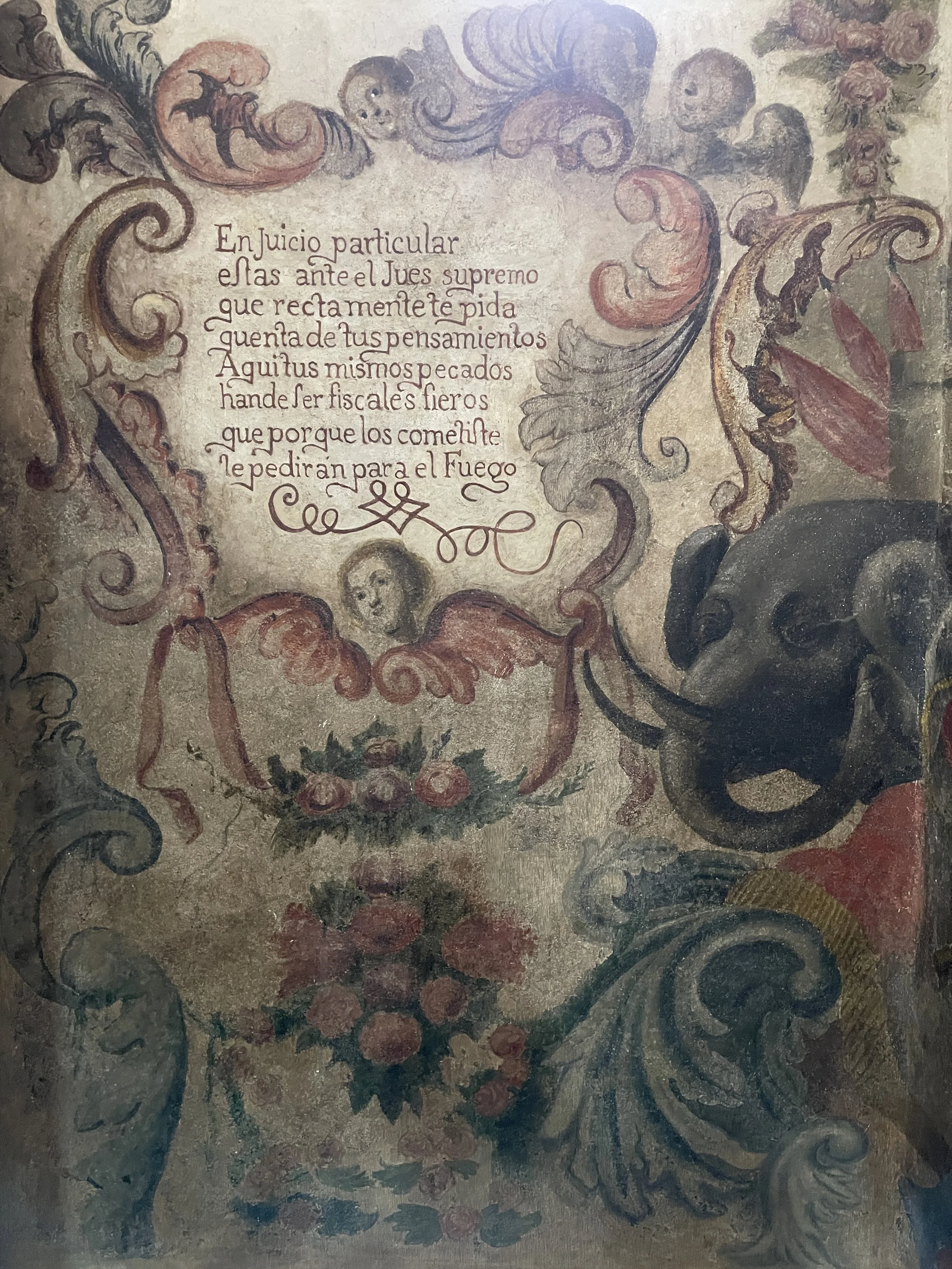

Inside, the ornate space feels more like a cathedral than a church. Constructed in two phases, the Gothic half follows the floor plan of the former mosque, while the enlargement initiated after the earthquake of 1580 reflects the evolution of architectural styles that rose in popularity during its extended completion and renovations, including both Renaissance and Baroque elements.

This altar is an impressive example of Spanish Baroque, a style known for its exuberance, grandeur and rich decorative elements.

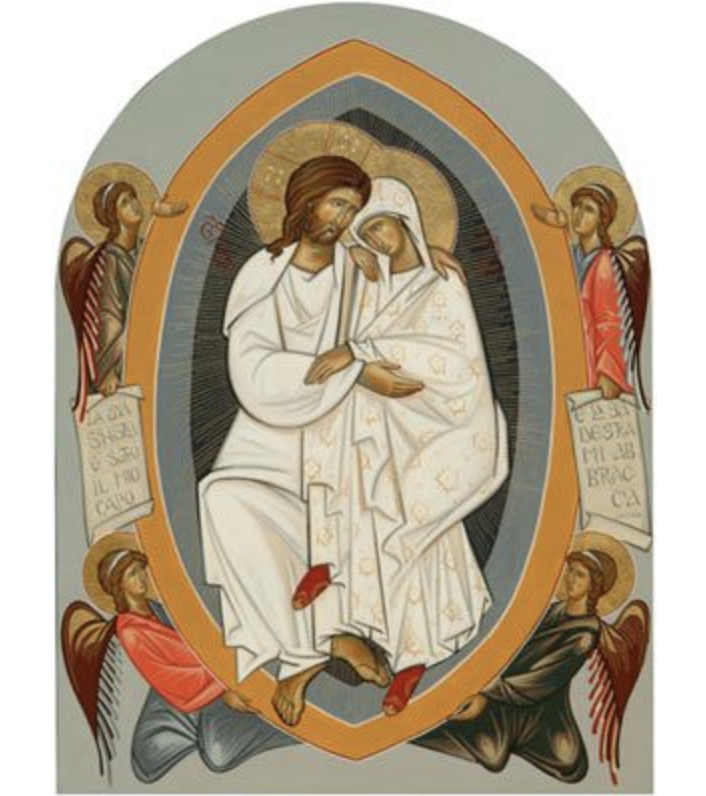

The Virgin de la Aurora shows Mary in her aspect as Our Lady of the Dawn, a beacon of hope and a source of spiritual guidance for Catholics.

Altar of the Sagrario

The central nave of the Gothic section features an ornate and detailed Baroque giltwood altarpiece. Standing within a niche beneath a Marian crown is the figure of the Inmaculada, the Virgin Mary, standing on clouds. She’s flanked by representations of her mother, Santa Ana; her father, San Joaquín; and the Arcangel San Rafael. Twisted Solomonic columns, covered with delicately carved grapevines and topped by Corinthian capitals, complete the tableau. During our visit, the revered image of the Virgen de la Aurora (Virgin of the Dawn) was displayed on an elaborate paso, or float used for processions.

The Christ child sits upon the shoulders of the giant Saint Christopher and holds a fancy rattle, er, globus cruciger, a small sphere with a cross affixed to its top, symbolizing his sovereign dominion.

Mural of San Cristobalón

The large-scale mural to the left of the altar depicts a larger-than-life San Cristobalón (Saint Christopher), the patron saint of travelers, carrying the baby Jesus upon his shoulders. It was painted by Rondenian artist José Ramos.

The dramatic statue of Nuestra Señora del Mayor Dolor (Our Lady of Sorrows) depicts the Virgin Mary with her eyes cast heavenward, heart pierced by a sword, her hands clasped in prayer.

Altar of Nuestra Señora del Mayor Dolor

To the right is a highly ornate Churrigueresque-style altar framing a red velvet-lined niche holding the processional figure of Nuestra Señora del Mayor Dolor (Our Lady of Sorrows), which belongs to the religious brotherhood of the Hermandad del Santísimo Cristo de la Sangre. The sculpture depicts the moment when Mary learns that her son will die for the sins of mankind. Her eyes are lifted upwards and her hands are clasped, holding a rosary. Most dramatically, her heart is pierced with a silver sword, and a pair of cherubs flutter menacingly beneath her — one appears to be holding a hammer, and the other, pincers.

The Renaissance-period choir screen is embellished with imagery of the apostles and other saints and has a lectern stand holding a 16th century antiphonal (choir book).

Coro

The choir screen was a Renaissance addition and features intricately carved cedarwood reliefs depicting the apostles and other saints. It’s no accident that it was placed strategically at the nave’s center as it served as a partition to divide the church into two social classes: aristocrats to the front and parishioners to the back. The lectern stand supports a 16th century antiphonal (choir book), its musical notations intricately inscribed on pages made of vellum.

The high altar of Santa María la Mayor has an elaborately carved wooden canopy that showcases the Holy Spirit, the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary.

Baldaquino of the Altar Mayor

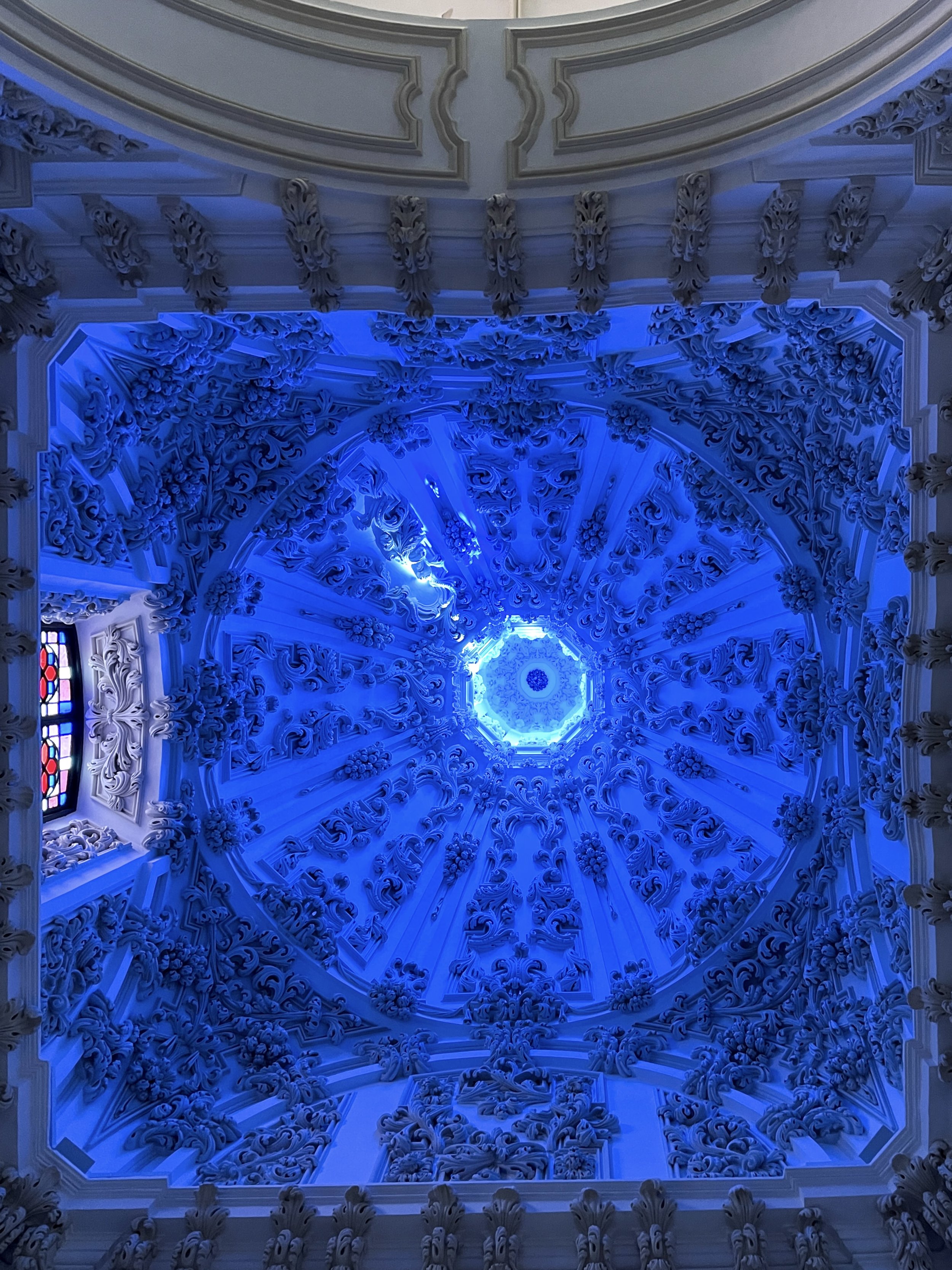

One of the most striking elements of the church is the impressive baldaquino, or canopy, located on the high altar under the central dome of the Renaissance nave. Carved from wood, it consists of four slender, finely carved Solomonic columns that support a towering highly decorated cupola topped by an angel.

The original altarpiece was destroyed during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and replaced by the baldaquino from Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles (Our Lady of the Angels).

Within the ornate structure are the Archangel Gabriel and the Holy Spirit in the guise of a dove visiting the Virgin to inform her that she will conceive and give birth to Jesus Christ.

Be sure to climb up to the rooftop, like Duke did, for a view of Ronda from above.

Up on the Rooftop

We passed through the doorway to the right of the altar and climbed the narrow steps of the winding spiral staircase leading to the roof and viewing deck.

Jo stands on a balcony overlooking the square and the Ayuntamiento, the City Hall.

While we were there, the late afternoon sun cast a soft, warm glow over the terracotta-tiled rooftops of the old city, and it was so clear that we could see the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains in the distance.

Views of the Old Quarter and the mountains beyond from the rooftop

Seen from above, the spiral staircase leading to the rooftop resembles a snail’s shell.

There’s a long bench if you need to rest or take a moment to enjoy the view. Make sure to peek through the small door at the top of the staircase to take in a bird’s-eye view of the interior of the church.

A figurine of the Baby Jesus with outstretched arms was one of Duke’s favorite pieces in the church’s museum.

Back Down on Earth

After exploring the rooftop, Jo, José, Wally and I returned to the ground floor and wandered through the church museum. It had several glass-front cabinets displaying various religious objects: vestments (clergy apparel), chalices and sculptures, including a life-sized glassy-eyed baby Jesus, which I imagine might get placed in the church’s crèche on Christmas Day.

The Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor is a short distance from the Puente Nuevo, but its location in the leafy park-like Plaza Duquesa de Parcent feels a world away from the overcrowded tourist area. –Duke

Colegiata Santa María la Mayor

Plaza de la Duquesa de Parcent s/n

29400 Ronda Málaga

Spain