A one-day itinerary for travelers looking to experience the best of Guanajuato City, including the Museo de las Momias, the Teatro Juárez and the funicular to the Pipila Monument and overlook.

If you’re staying in San Miguel de Allende, you’ve gotta take a day trip to Guanajuato — and we’ve got the perfect itinerary for you.

Even if you’re not into displays of desiccated corpses, the charming and colorful capital of Guanajuato, Mexico has plenty to offer. It makes for a delightful day trip from the tourist hotspot San Miguel de Allende.

“The sights in Guanajuato are equal parts beautiful and bizarre.”

A Brief History of Guanajuato

Originally inhabited by indigenous groups, the region was conquered by the Spanish, and the town of Guanajuato was incorporated in 1554.

Like San Miguel, Guanajuato was an important and wealthy colonial city due to the region’s large silver deposits. It played a pivotal role in Mexico’s struggle to break the Spanish yoke. The city was the site of the first major battle of the Mexican War of Independence, which took place in 1810. Guanajuato also played a significant role in the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910 — it was the site of the first battle (which the revolutionaries won).

Hop to it! Follow this walking tour of charming and quirky Guanajuato.

Guanajuato Day Trip Itinerary

With this tried-and-true one-day itinerary, you’ll experience the best of colorful and quirky Guanajuato, taking in the top attractions, flavors and vistas that this charming city has to offer.

Start your day at the Mummy Museum, then head to the Plaza of the Frogs before strolling along the main street of town. Here are the places we recommend stopping at, before ending with a funicular trip to overlook this incredible mountain town. With its vibrantly painted buildings and lively plazas, Guanajuato is one of Mexico’s most beautiful colonial towns.

Museo de las Momias

Looking for a bit of spook-tacular fun? The Museo de las Momias has you covered. In our estimation, this is the town’s main attraction. The macabre museum features the desiccated husks of some of the city’s former residents who couldn’t pay their burial tax, were dug up and discovered to be naturally mummified due to the arid climate. It’s a morbidly fascinating experience that’s not for the faint of heart.

LEARN MORE: The Haunting and Horrific Mummy Museum of Guanajuato

Explanada del Panteón Municipal s/n

Plaza de las Ranas

Hop on over to Plaza de la Hermandad, also known as Plaza de las Ranas (Frog Plaza). The centerpiece is a fountain created by French sculptor Gabriel Guerra and installed in 1893. It looks a bit like a swimming pool, but the stars of the show are the whimsical frog statues made of stone that decorate the open plaza.

Why frogs? The name Guanajuato comes from the indigenous Purépecha words Quanax-Huato, which means “Place of the Frogs.” One theory is that the town took its name from a pair of colossal boulders resembling giant frogs. Seeing this as an auspicious sign, the Purépecha decided to settle here. They were a powerful empire that dominated western Mexico prior to the Spanish conquest.

Fun fact: Guanajuato was the birthplace of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who referred to himself as “el Sapo-Rana,” the Frog-Toad.

Galereña Dulces Típicos de Guanajuato

Want something sweet? Next stop: Galereña Dulces, a candy store that’s been around since 1865. They’ve got all kinds of traditional Mexican sweets — but don’t get your hopes up about mummy gummies. Much to our dismay, those don’t exist.

The cellophane-wrapped caramel-colored confections we found are actually known locally as charamuscas. They’re a type of hard candy made from spun boiled cane sugar twisted into a mummy figure shape. Which, now that I think about it, these gnarly, crunchy versions are actually more fitting.

Avenida Benito Juárez 188

Empanadas MiBu

Feeling a bit peckish? Time for a snack at Empanadas MiBu. I always say: If there’s a Heaven, there will be empanadas up there. These tasty little pockets of joy come in all sorts of varieties, from savory (rajas con queso are my fave) to sweet (you can never go wrong with Nutella), and are the perfect snack to munch on while exploring the city. They’re made to order and served in paper bags, making them the perfect handheld food to eat on the go.

Avenida Benito Juárez 65-A

Jardín Reforma

Escape the hustle and bustle of the city by taking a stroll through this serene park that’s just past Empanadas MiBu. Head through the classical arch into a tranquil oasis that’s surprisingly peaceful for being mere steps off the city’s main drag. The loudest sound you’re likely to hear here is the gurgling of the fountain in the center or the chirping of birds.

Be sure to pop into G&G Cafe, the coffeeshop in the corner of this small park, if you need a caffeine fix.

Basilica of Our Lady of Guanajuato

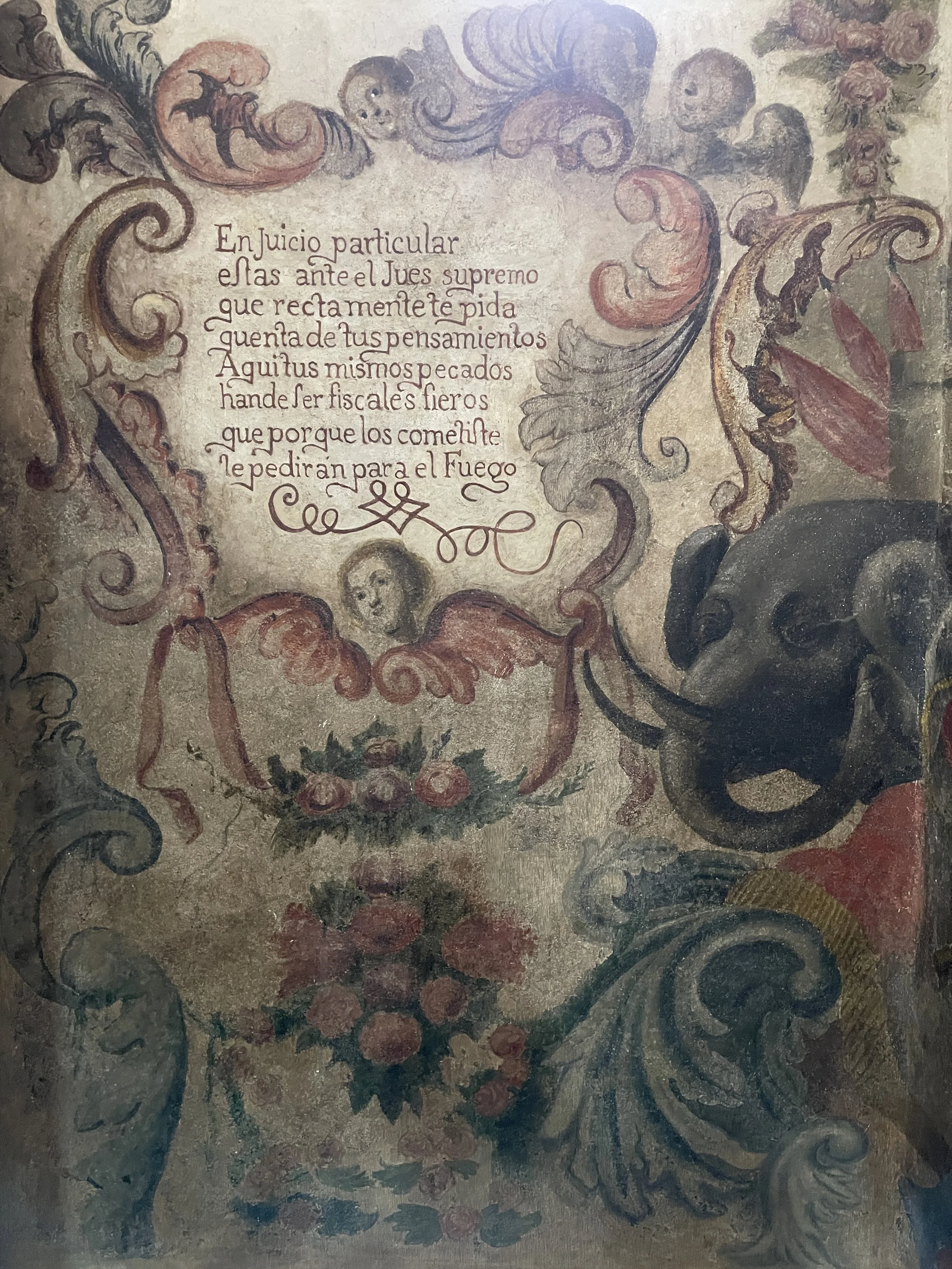

Continue down Avenida Benito Juarez until it turns into De Paz. The yellow Basílica Colegiata de Nuestra Señora de Guanajuato, dedicated to the city’s patroness, Our Lady of Guanajuato, is hard to miss. The yellow edifice stands proudly on the historic Plaza de la Paz (Plaza of Peace), the main square. However, unlike most Spanish colonial cities, the plaza is not a square but a triangle, to better fit Guanajuato’s hilly geography.

The church’s façade was designed in the Mexican Baroque style and is adorned with carvings of saints and features two bell towers and a red clay dome. The interior is just as impressive, with soaring arches, intricate gold leaf detailing and a stunning main altar that encompasses the local likeness of the Virgin Mary.

Calle Ponciano Aguilar 7

Teatro Juárez

While you’re in the vicinity, stop by the Teatro Juárez, a majestic Neoclassical theater, built from 1872 to 1903. Bronze statues of the Greek Muses, who represent the arts and sciences, stand on the roof.

We didn’t get a chance to go inside, but it looks impressive, awash in red velvet and gold details, with a colorful ceiling motif in the Neo-Mudéjar style, a nod to the mix of Spanish and Arab design popular in the South of Spain.

The landmark hosts a wide variety of performances, from concerts and operas to plays, international movies and dance. It has served as the main venue of the Festival Internacional Cervantino since 1972.

De Sopena 10

Funicular and El Pipila Monument

End your stroll through town with a ride on the funicular. The station is close by the Teatro Juárez. A cable car system built in 2001 takes you up the hill to an overlook and costs 60 pesos (about $4) for a roundtrip ticket. We had to stand in line for a bit, but it was worth the wait. The ride up is pretty fun — but the view is breathtaking. I was utterly captivated by the hilly landscape and the colorful, densely clustered patchwork of buildings that stretched out before us. I leaned against the railing and gazed out at it for a long time. It’s easy to see why the enchanting city center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Pro tip: When facing the city below, head off to right for a less-crowded viewing platform above the basilica.

Crowds of tourists and locals gather in the shadow of the El Pipila monument, a towering 80-foot statue built in 1939 to commemorate a hero of the Mexican War of Independence.

So who exactly was this Pipila fellow? His real name was Juan José de los Reyes Martínez, who, during the siege of Guanajuato, crawled towards the Alhóndiga de Granaditas, a granary used as a fortress by Spanish troops. He had a large stone slab used to grind corn (a pipila — hence his nickname) on his back. Once he reached the door, he used the stone to break it down, allowing the rebel forces to enter and defeat the Spanish troops.

De La Constancia 17

Outside the Mummy Museum, we watched a performance of men in drag mock-fighting. The sights in Guanajuato are equal parts beautiful and bizarre.

SMA Day Trip

All told, we spent about four hours in Guanajuato. We hired a driver from San Miguel de Allende through our hotel’s concierge. The ride is an hour and a half each way. We got dropped off at the Mummy Museum and then texted our driver at the end of the day once we on our way back down on the funicular.

From truly disturbing to truly delightful, Guanajuato is a day trip not to miss. –Wally