Take a virtual tour to see our favorite statues of famous pharaohs and tomb relics.

If you can’t actually visit the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, do the next best thing: Virtually tour some of the exhibits below

It’s bad enough that I’ve been self-quarantined inside our home for a week and a half now, with no end to this isolation in sight. On top of that, I seem to have contracted the dreaded coronavirus, with lingering symptoms of COVID-19.

To make matters worse, I’ve had to cancel a mini-sabbatical to Spain, where I had planned to visit my good friends Jo and José in Málaga, fulfilling my dream of experiencing Semana Santa and touring the colorful towns of the South of Spain, with their charming Moorish influence.

Plus, it’s looking as if Duke and I will also have to forgo our trip to Athens and the Greek Isles this spring as well.

“Most of us find ourselves looking for ways to live vicariously, to continue to explore the world — even if that means virtually. ”

Like many of you, travel is what we look forward to. In many ways, it’s what makes life worth living. Planning a trip abroad gives Duke and me something to dream about. In a time when the world wasn’t so chaotic, our future travels would be what got us through tough times. Now we have no idea when we’ll be able to take a vacation again. The world is on lock-down, frozen in place. It’s not a comfortable feeling, and the real extent of the crisis might not be apparent for weeks or even months.

With so much time on our hands, most of us find ourselves looking for ways to live vicariously, to continue to explore the world — even if that means virtually.

Here’s a photographic tour of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, showcasing some of our favorites statues, sarcophagi and other works of art. (To get a feel for the delightfully dilapidated museum, read Duke’s write-up.)

A gray granite statue of Ramesses II as a child protected by the god Horus, depicted as a falcon.

The fragmented sculpture of the goddess Mut and her husband, the chief god Amun, is composed of 79 pieces. The head of the goddess was discovered by French Egyptologist August Mariette in 1873. Other parts were unearthed during additional excavations in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak and sent to the museum, where they were reassembled.

The colossal figures of Amenhotep III, who ruled around 1386-1353 BCE, and his wife Tiye survey the great hall of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. The statue was discovered at Medinet Habu. Tiye, whose arm wraps around her husband's waist, is the same size as the king, demonstrating her equal status as a powerful and influential queen.

This statue, carved in a variety of sandstone known as graywacke, shows the Fourth Dynasty Pharaoh Menkaure wearing the crown of Upper Egypt. The king, who was born in 2532 BCE, is flanked by the goddess Hathor (left), crowned with a solar disc between cows horns, and Anput (right), the personification of the 17th nome, or district, of Upper Egypt. Note the jackal above her, referring to her husband, the god Anubis.

A realistic-looking sycamore wood figure with white quartz and resin eyes from the Fifth Dynasty, depicting a khry-heb, or lector priest, named Ka-aper. He was responsible for transcribing religious texts and reciting hymns in the temple and at ritual festivals.

Skeleton of a dog. Ancient Egyptians were known to sacrifice and mummify a variety of animals.

An alabaster statue of the high priestess Amenirdis, who held the title of God’s Wife of Amun during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty. She’s wearing a diadem of cobras and holding a small whip, or flagellum, bent to resemble a lily.

A row of small stone sarcophagi stand in front of a chipped wall typical at the Egyptian Museum

A statue of Meryre and his wife Iniuia. Meryre began his career under the reign of Akhenaten, the so-called Heretic King who ruled from 1353-1336 BCE in the Eighteenth Dynasty, as steward and scribe of the Great Temple of the Aten in Armana, Akhenaten’s capital city, and later as high priest at the temple of Aten at Memphis.

Dwarves commanded respect in Ancient Egypt, thought to possess divine gifts. One of the much-loved gods of the time, Bes (right), was depicted as a dwarf.

A granite sarcophagus lid of a dwarf named Djeho from the Thirtieth Dynasty. Inscriptions on the lid indicate that he was employed to dance at burial ceremonies connected to the sacred Apis bull.

This painted limestone head of Hatshepsut originally belonged to one of Osiride statues resembling the god of the underworld, Osiris, at Deir el-Bahari, the female pharaoh’s mortuary temple.

This granite sphinx was one of several that once stood at Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. This remarkable woman ruled Egypt, first as co-regent for her nephew/stepson Thutmose III and subsequently as pharaoh.

Another sphinx of Hatshepsut, this one painted limestone. It’s believed to have originally stood at her mortuary temple. Unusual for Ancient Egypt, her face is surrounded by a leonine mane.

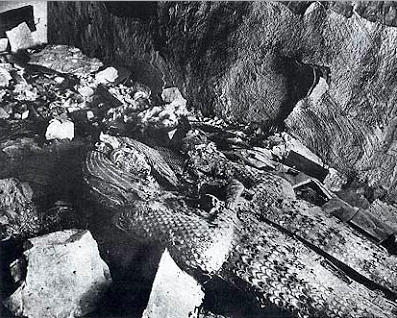

A detail of the outermost shrine that enclosed the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. Composed of gilt plaster over wood with a faience inlay, it bears protective symbols: the djed, or spine of Osiris, and the tjet, or Isis knot.

A diorite statue of the Fourth Dynasty Pharaoh Khefren, who may have ruled around 2558-2532 BCE, seated on a throne, protected by the outstretched wings of a falcon, a symbol of the god Horus. The eagle is on the back, so you unfortunately can’t see it from this angle.

A statue of the lion-headed goddess of war, Sekhmet. Don’t let her calm expression fool you: She could be violent and was given various titles, including Mistress of Dread, Lady of Slaughter and She Who Mauls.

This compact granite block statue depicts Senenmut, the favored official and director of building works under Hatshepsut, who reigned from 1479-1458 BCE, during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Senenmut held many roles, one of which was tutor to Hatshepsut’s daughter, Princess Neferure. The strange style of statuary was common for tutors. The head of the young royal emerges from Senenmut’s cloaked, protective form.

Model soldiers carrying shields and spears from the tomb of a pharaoh. Fun fact: The bravest soldiers were given amulets shaped like flies, to show that they had stung the enemy.

Funerary models carved of wood show scenes from everyday life. Placed in a pharaoh’s tomb, they assured that he would have all he desired, including food and drink, in the afterlife.

A gray granite statue of Tutankhamun depicted as Khonsu, a moon god whose name means Wanderer, son of Amun and Mut. The Boy King wears the sidelock braid of youth and is holding a crook, flail and djed pillar.

A 2nd millennium BCE funerary stele found at Abydos that may or may not depict a ruler named Sobekhotep and his wife.

This red granite statue depicts Ramesses II (left) and the creator god, Ptah (right). Ptah held a close relationship to the primeval god Tatenen, whose name means Risen Earth, referring to the primordial mound that emerged from the watery chaos at the beginning of the world. –Wally

The Egyptian Museum

Tahrir Square Rd.

Cairo, Egypt