Eye-opening insights into Muslim practices, including fasting, iftar, suhoor, zakat and the Night of Power.

Ramadan: when Muslims don’t eat, drink water, smoke, have sex or doing anything bad during the day for an entire month?! Learn more about this holiday.

“Ramadan’s been interesting,” my friend living in Qatar once told me. “It’s only been two days and it’s already a country full of cranky, sweaty, dehydrated, hungry people. It’s no way to live.”

The concept of not eating, or even being allowed to drink water, during daylight hours for an entire month seems so foreign to us Westerners — and, yes, downright bonkers. It can’t be healthy, for one thing.

“Ramadan is like Lent for Catholics.

Only instead of giving up something you love, you’re giving up something you need to survive. ”

You see, Ramadan is a bit like Lent for Catholics. Only instead of giving up something you love, you’re giving up something you need to survive.

Ramadan is a time of spiritual reflection, self-discipline and community. But let’s be real — it’s also a time of intense hunger, caffeine and nicotine withdrawal, and dramatic mood swings.

But these sweeping generalizations miss the point. I didn’t have the full story of why Muslims celebrate Ramadan. So I decided to do some digging.

Fascinating Facts About Ramadan

Ramadan is based on the lunar calendar, which means it starts 11 days earlier each year than the previous year. It takes 33 years for Ramadan to cycle back to a particular starting date. And once in a very blue moon, like in 1997, two Ramadans will fall within the same calendar year. The next time that will happen: 2033.

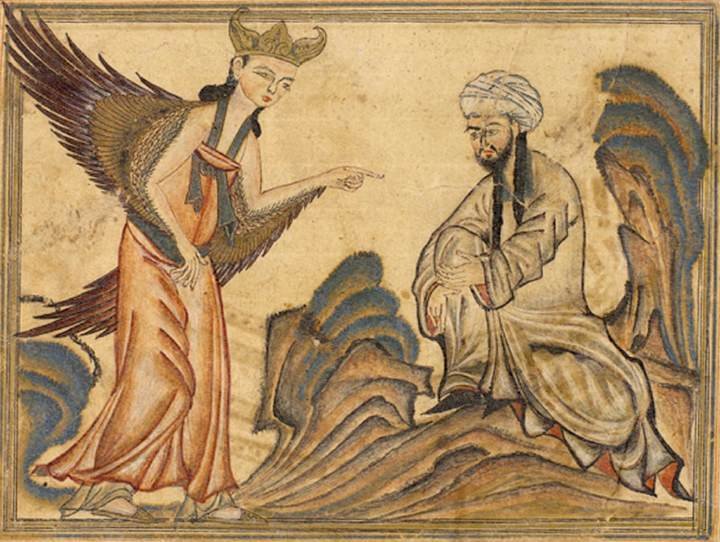

The holiday began in 624 CE and commemorates the month in which the Prophet Muhammad is said to have received the first revelations of the Quran, the holy book of Islam, from none other than the angel Gabriel.

The angel Gabriel delivers the Quran to the Prophet Muhammed — the event celebrated during Ramadan.

The word Ramadan comes from ramida, an Arabic root that means scorching heat or dryness. And no, it’s not referring to people’s parched throats on a hot day but the fact that Ramadan originally fell during the summer season.

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam, which are the basic duties that every devout Muslim must follow. The other pillars are prayer, declaration of faith, charity and pilgrimage.

Some years there are more hours of fasting due to longer daylight hours. The hours of fasting also change substantially throughout the world based on the hours of daylight in various locations.

Not everyone has to fast, though. There are some exceptions, such as children (you’re on the hook only after puberty), and those who are elderly, sick, traveling, pregnant, menstruating, breastfeeding…or all of the above. You can either make up the fasts later or feed a poor person for each day you miss.

Fasting during Ramadan isn’t just about abstaining from food and drink — you have to forgo sex, smoking, and anything else deemed indecent or excessive. Muslims also try to avoid anger, gossip and bad deeds during the month.

You might think that fasting during Ramadan would work as a crash diet. But that’s not always the case. In fact, some people actually gain weight because they overeat after breaking their fast at sunset and shortly thereafter fall into bed.

Once the sun has gone down, people can break their fast with the meal called iftar.

Iftar and Suhoor: Time to Stuff Yourself Silly

Break their fast you say? Well, it’s not like people could survive not eating or drinking water for an entire month. So, once the sun has set, Muslims have a meal called iftar, which traditionally starts with dates and water, as well as other foods like soup, rice and bread.

Dates are the traditional food to break your fast once the sun sets during Ramadan.

Iftar is a time for celebration and indulgence. It’s a chance to gather with loved ones, share delicious food and thank Allah for the blessings of the day.

People prepare plates of food for iftar. It must be hell cooking delicious-smelling dishes when you haven’t eaten all day.

Muslims then catch a few Z’s before getting up before dawn to eat a meal called suhoor. It’s a delicate balance between filling up enough to last until sunset without feeling like you’re going to burst.

Prayer in Cairo by Jean-Leon Gerome, 1865

Prayer and Charity: The Chance for Forgiveness

During Ramadan, Muslims attend special night prayers called taraweeh at mosques. They seek to deepen their relationship with Allah and cultivate a sense of spiritual peace and tranquility.

There’s also a strong focus on helping others. Islamic teachings encourage Muslims to set aside a percentage of their accumulated wealth to donate to charity (zakat) and do good works for the neediest in their community. “The best charity is that given in Ramadan,” Muhammed said.

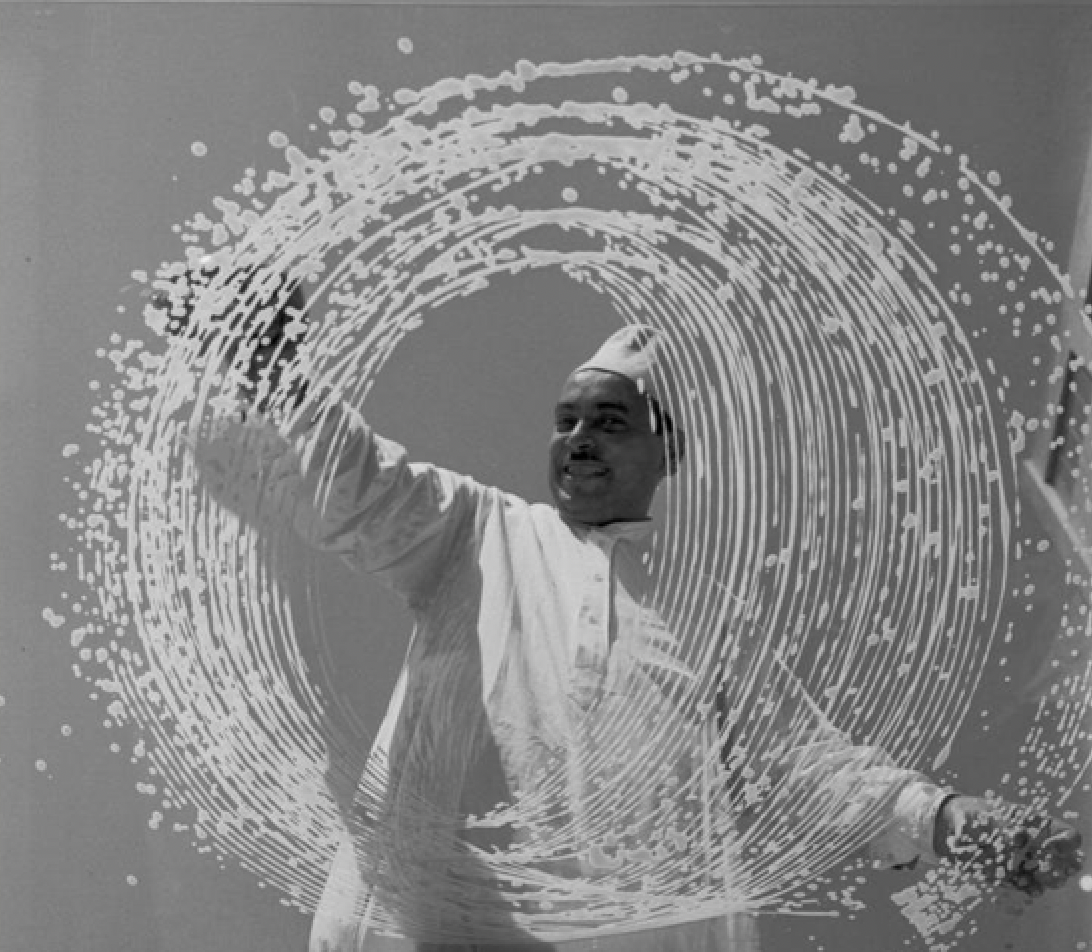

The Night of Power is a mysterious occurrence during Ramadan. Muslims can seek it through intense prayer at a mosque during the last 10 days of the holy month.

The Quest for the Night of Power

One of the most important moments of Ramadan is the Night of Power, or Laylat al-Qadr. The Quran declares that it’s “better than a thousand months” (Surah Al-Qadr, 97:3).

I don’t quite understand what the Night of Power entails; it sounds a bit like an epiphany. According to the Prophet Muhammad, it’s an opportunity to ask for forgiveness of your sins.

But the Night of Power is elusive, mysterious, intensely personal. One way to seek the Night of Power is through the practice of i’tikaf, which involves secluding yourself in a mosque for the last 10 days of Ramadan. This intense focus on prayer and contemplation increases your chances of finding the Night of Power.

Many Muslims spend more time praying during Ramadan.

Another way to seek the Night of Power is through increased acts of worship, such as reciting the Quran, performing extra prayers or giving zakat.

Finally, Muslims can seek the Night of Power through supplication and heartfelt dua, the act of calling upon Allah. Good news: “A fasting person, upon breaking his fast, has a supplication that will not be rejected,” Muhammad said.

Massive amounts of people come together to celebrate Eid al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan.

Eid Al-Fitr: A Well-Earned Celebration

After the month of fasting, prayer and spiritual reflection, Muslims around the world come together to celebrate Eid al-Fitr, the Festival of Breaking the Fast. (It’s pronounced like Eed al-Fitter.) It’s a time of joy, feasting and giving thanks.

The day begins with the Eid prayer, followed by a sermon in which the imam reminds the community of the lessons learned during Ramadan and encourages them to continue their spiritual growth throughout the year.

People go to a mosque on Eid al-Fitr — and after the sermon, the feast begins.

After the prayer and sermon, Muslims exchange greetings of “Eid Mubarak” and engage in acts of charity and kindness.

Finally, Eid al-Fitr is a time of feasting and indulgence, with traditional sweets and delicacies being shared among family and friends.

Girl Reciting Quran by Osman Hamdi Bey, 1880

Ramadan and Self-Transformation

I now have a better understanding of Ramadan. The religious holiday is a spiritual detox, a month-long opportunity for Muslims to purify their hearts, minds and souls. It’s a time to leave behind bad habits and negative behaviors, and focus on strengthening their connection with Allah and becoming better individuals.

It’s also an opportunity to wipe the slate clean. As the Prophet Muhammad said, “Whoever observes fasts during the month of Ramadan out of sincere faith and hoping to attain Allah’s rewards, all his past sins will be forgiven.”

Ramadan is a time of self-reflection, charity and forgiveness.

I’m sure that the intense sacrifice Muslims make during Ramadan leads to some pretty powerful revelations about one’s self and helps people be more empathetic to the less fortunate.

“Ramadan is a time for us to remember what is essential in life, to let go of our attachments to the trivial and the mundane, and to connect with the divine and the transcendent,” says Omid Safi, a professor of Islamic studies at Duke University.

Maybe that’s not so unhealthy after all. –Wally