Get the additional ticket at Saqqara to see the finely preserved Ancient Egyptian mastaba of Pharaoh Teti’s vizier.

It should come as no surprise that Wally and I love exploring old cemeteries, especially ones that have monuments and mausoleums dedicated to famous people — from the park-like Père Lachaise in Paris, France to Graceland Cemetery, the final resting spot for Chicago’s version of nobility, not far from where we live.

Before our trip to Egypt, the allure of exploring the culturally rich and diverse monuments of antiquity were obviously a large part of our ambitious itinerary. We had a brief window of only two days in Cairo — one of which was to see the Egyptian Museum, the other the Pyramids of Giza.

But when our friend Margaret suggested we add on the less touristy (yet, some would argue, equally important) sprawling ancient burial ground of Saqqara — home of the oldest known pyramid in Egypt and necropolis to kings and nobles dating back 3,500 years or more — we thought, sign us up!

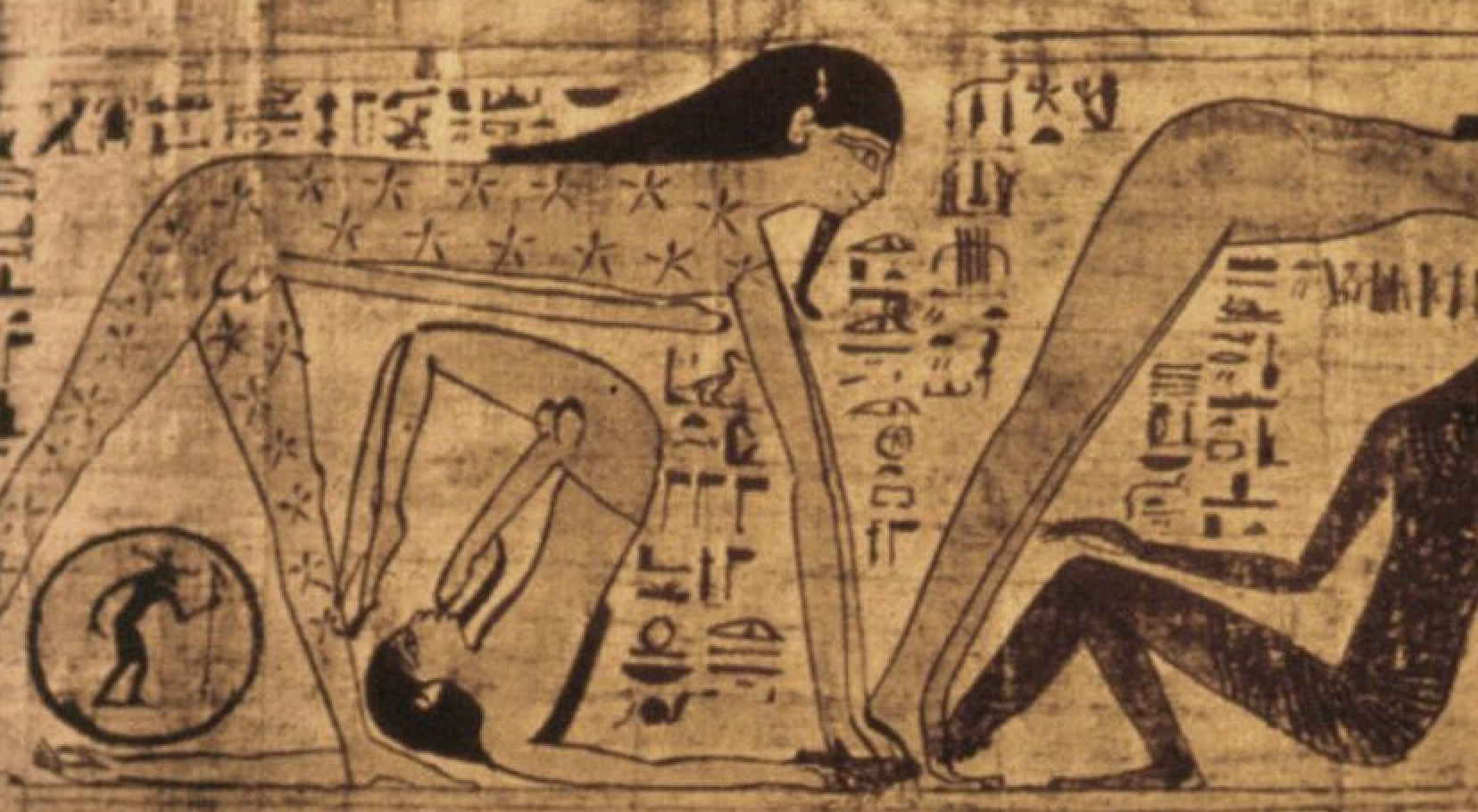

A bas-relief on the wall leading to the suite of Mereruka’s son Meryteti shows nude male figures. The side-lock braids was a hairstyle worn by youths

Misguided at Saqqara

We had just finished exploring the parchment-hued limestone mastaba tombs of the Unas complex and had become increasingly frustrated with our guide, Ahmed. Earlier in the day, we had visited Giza and missed seeing the Solar Boat Museum as he apparently hadn’t included it as part of our pre-arranged itinerary. How unreasonable of us to assume we’d have a guide who would provide us options instead of rushing us through the sites so he could end his day early.

“And that’s Saqqara,” Ahmed told us.

“But what about that tomb with the cool statue?” Wally asked.

Ahmed stared blankly at us as if he didn’t have the faintest notion of what we were talking about.

“Hold on,” Wally said, flipping through his notebook. “Here it is! Mereruka’s tomb.”

“That costs extra,” Ahmed said.

“What part of of ‘we are only here once and want to see everything and are happy to pay extra’ don’t you understand?” a frazzled Wally exclaimed.

Ahmed acted like a petulant child as he led us back to the car to reluctantly return to the kiosk to purchase the additional tickets. (They cost a mere 80 Egyptian pounds, or about 5 bucks, by the way.)

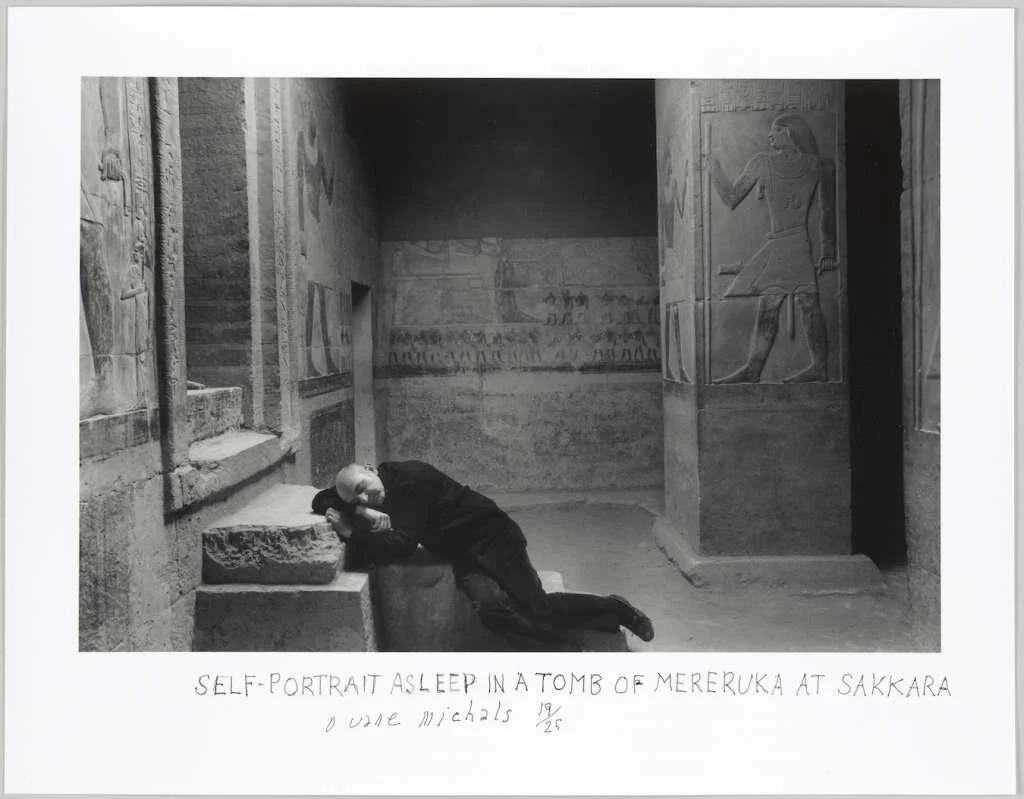

The renowned gay photographer Duane Michals takes an interesting self-portrait at the Tomb of Mereruka — surely one that our guide Ahmed would not have approved of

During the Old Kingdom, from around 2686-2181 BCE, the wealthiest and most important non-royal members of Egyptian society were interred in monolithic bench-like burial structures referred to as mastabas. Mereruka served as the vizier, chief justice and son-in-law under the rule of the Sixth Dynasty Pharaoh Teti. As befitted his influential political position, he was buried in the largest of the non-royal tombs in Saqqara.

On either side of the tomb entrance, the vizier Mereruka can be seen with his wife shown in a diminutive size in front of him

Little Women

Outside the entrance to the mastaba, relief portraits on the jambs on either side of the unassuming doorway depict Mereruka with a diminutive figure of his wife Sesheshet Watethathor standing at his feet and only coming up to about his knee. This symbolic device was employed in Egyptian art to show an individual’s importance or authority. The larger the scale, the more powerful; by extension, the lesser the scale, the more passive the role. Such was the lot of most women in Ancient Egypt (though there are exceptions to every rule, as King Hatshepsut proves).

In this historic photo from 1934, an artist copies the inscriptions and sketches the tomb

A Marvelous Mastaba

The mastaba was first excavated in 1892 by French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan and actually contains three tombs in total, divided into 31 interior chambers. Of these suites, 21 are dedicated to Mereruka, five to his wife and five for his son Meryteti.

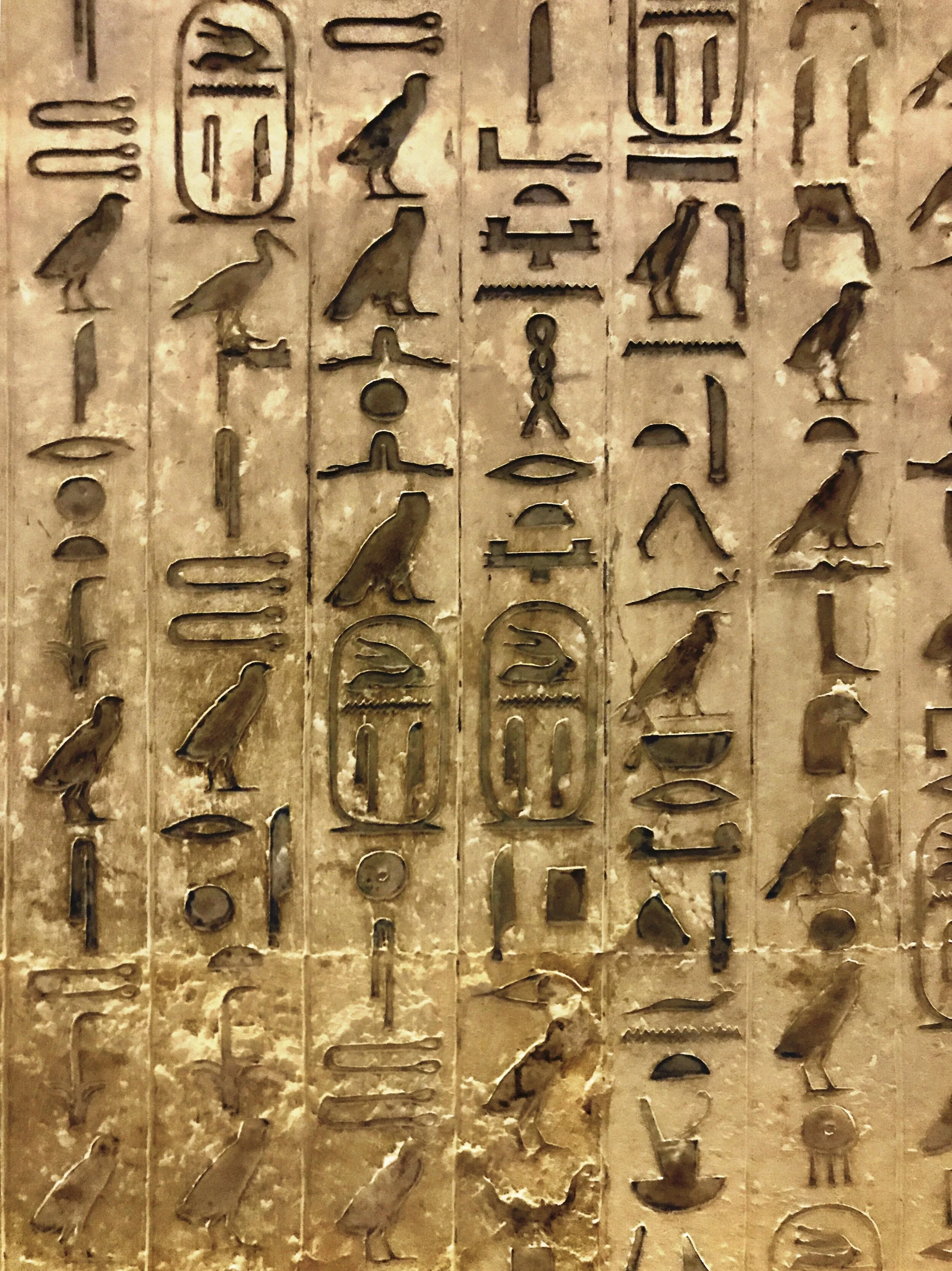

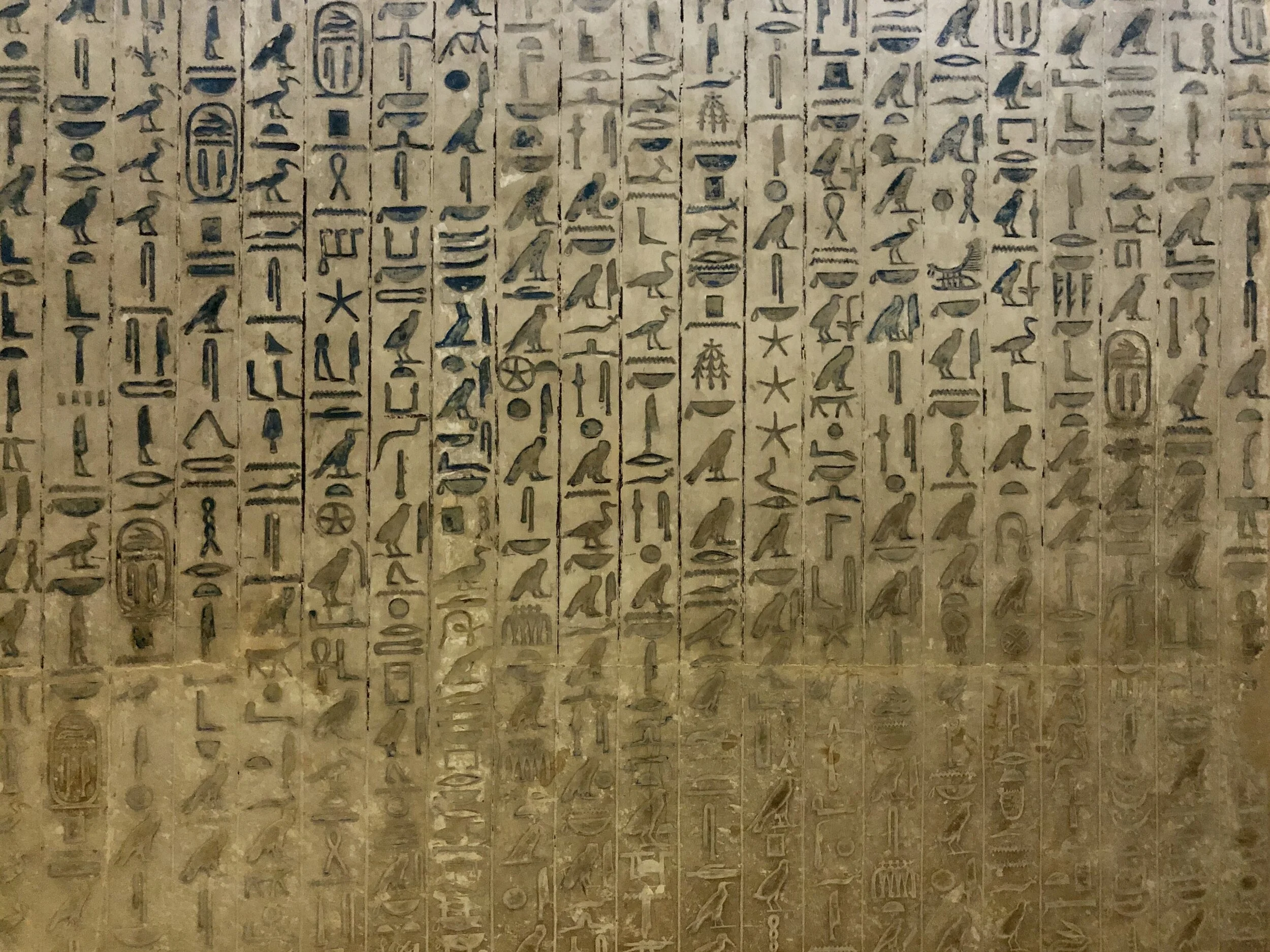

Inside the well-preserved tomb are finely detailed two-dimensional reliefs depicting scenes of everyday life — including activities the deceased vizier and his family wished to continue in the afterlife. Amongst the birds and beasts, hieroglyphic inscriptions on the walls and corridors of Mereruka’s suites bear his various titles.

Although their heads are missing, we admired a relief depicting the vizier and his wife. It’s a timeless image of two entwined hands preserved in stone: Mereruka leading his beloved through the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian tombs had false doors, through which the spirit could come and go

If you carve it, it becomes real: Depictions of offerings were as good as the real thing to Ancient Egyptians

Farther into the tomb was the requisite false door, an architectural feature allowing the deceased to pass between the world of the living and the dead. Recessed rectangular panels are inscribed with a hieroglyphic list of provisions and facing inward at the bottom are six standing figures of Mereruka. Centered above the door the deceased is depicted seated on a stool with the fore and hind legs of a lion before a table of ritual offerings. Below this is a raised slab where food and drink could be placed by the living for the benefit of the dead.

The famous statue of Mereruka is a large part of the appeal of this tomb complex

The Statue of Mereruka: A Step in the Right Direction

The largest room, and the one photographed in our guidebook, is the mortuary chapel, an impressive six-pillared ceremonial chamber, where Mereruka’s priests and family would come to pay homage to the deceased vizier. Quietly presiding over the hall is a life-size statue of Mereruka stepping out from a recessed doorway.

On the floor of the room is a stone ring.

“What was that for?“ Wally asked Ahmed, who said he had no idea.

In my research, I learned that it was used for tethering sacrificial animals, including the sacred Apis bulls. Hopefully Ahmed reads this post and learns something — besides how to properly behave as a guide.

We hope this hedgehog was going to be a pet — and not a sacrifice

Mereruka holds hands with his son

A scene depicting sculptors and metal workers — note that some of the artisans are dwarfs

As Wally and I wandered about, Ahmed caught a small group of American tourists touching the reliefs on the walls. For a brief moment, he became passionate and shouted, “Don’t touch! You’re breaking my heart!” Then, he muttered to us, “Why would they think it’s OK to touch the walls? You wouldn’t touch the paintings in the Louvre!”

Then, in a moment, he was back to his sullen self, annoyed that we still wanted to explore. He told us he’d be waiting for us outside — but not before informing us that no photography was allowed. We obviously didn’t take heed. –Duke