Parque Los Bebederos once hosted fashionable events, which the modern architect Luis Barragán would use as a sales pitch to entice homebuyers to the Mexico City suburb of Las Arboledas.

Our guide, Martín, with Duke, got us to appreciate even this park, showcasing works by Barragán that have fallen into disrepair.

Paseo de los Gigantes. Promenade of the Giants. An evocative name — but when you visit, you might wonder where these mythical monstrosities can be found.

Stop and look around this green space outside of Mexico City. The answer is right in front of your eyes. See the tunnel of majestic, gnarled bark eucalyptus trees? Those are the giants for which the park is named.

A massive, gnarled eucalyptus tree — one of the namesake “giants” of this linear park

It was our last stop on our half-day tour of Luis Barragán’s suburban designs: Torres de Satélite, Fuente de los Amantes and the amazing Cuadra San Cristóbal.

Barragán was fond of designing paseos. These long, thin green spaces now act as medians dividing grand boulevards, but they were once country paths used for horseback riding.

For this is horse country, a suburban enclave for equestrian aficionados northwest of CDMX. In fact, the main purpose of this particular linear park was to generate interest in the local community of Las Arboledas. Los Gigantes was a social hotspot, offering stands to view races at the horse track that once stood here. (Nothing remains, sadly — all you can see now are homes. It would have been cool if they had incorporated the track to shape the neighborhood like they did in La Condesa with Avenida Amsterdam.)

These narrow parks, set along medians, followed old country roads once used for horse riding.

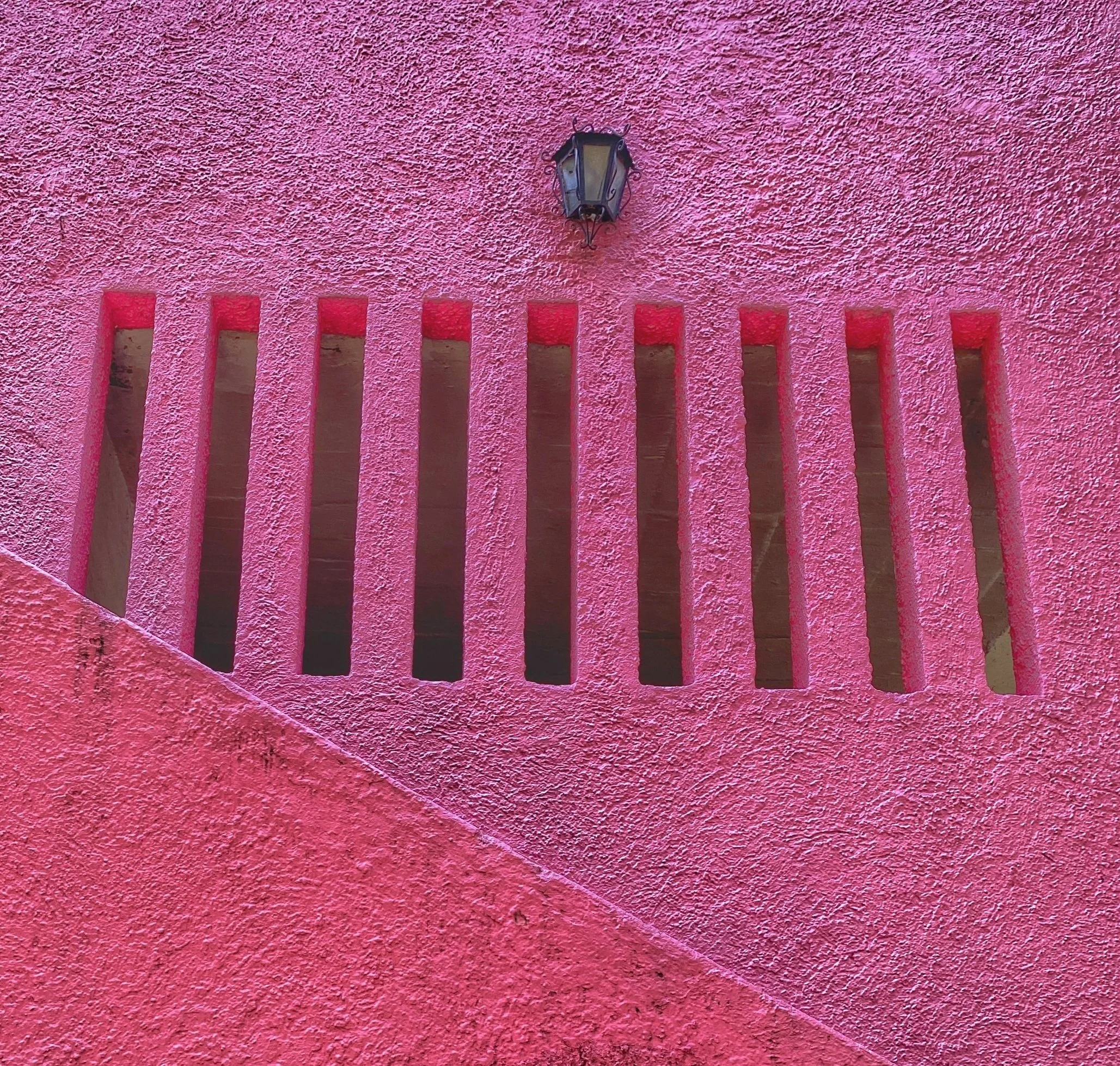

The faded red viewing stands were used for social events to watch horses gallop around a no-longer-existent racetrack.

Barragán held events in Los Gigantes, though little evidence of its fashionable past remains. The park is but a shadow of its former glory.

As with Frank Lloyd Wright, some of Barragán’s designs might have looked impressive but just don’t stand the test of time. A fountain here with a bright tangerine-colored backdrop lacked a proper foundation (not to mention was a colossal waste of city water), and the basin has been drained.

While we gazed upon it, a guy on a BMX bike kept riding through the empty fountain, treating it as a ramp to practice his tricks and jumps.

Barragán’s orange fountain at Los Gigantes is now drained. Its foundation was sinking — and it used quite a bit of city water.

The red concrete viewing stands look outward, away from the park, once facing the horse track. Tucked behind a wall, there used to be a bar where people would get refreshments to enjoy the show, our guide, Martín, told us.

“I wish it was still a bar,” I muttered.

The red structure in the background once housed a bar for fancy cocktail parties Barragán would host to lure rich horse enthusiasts to buy land in the local development.

All this spectacle was designed to attract the CDMX élite. “Barragán was clever,” Martín continued. “In essence, he was saying, ‘This prestigious life could be yours. You can raise your kids here. Why don’t you buy a piece of land?’”

Barragán grew up with horses and was passionate about the equestrian lifestyle — but he was also, one imagines, well paid to promote the area.

The blue wall marks the end of the park.

Plaza del Bebedero

Continuing along in the park, we came to the Plaza y Fuente del Bebedero (Plaza and Fountain of the Trough. The long, thin rectangular horse trough, like the other fountain, is now empty.

The trough is considered the centerpiece of the green space — in fact, the area is sometimes called Parque Los Bebederos (although there’s only one).

The Fuente del Bebedero (Fountain of the Trough) used to be a watering hole for horses but is now empty.

A white wall nearby acts as one of the canvases for the play of shadows that’s a Barragán trademark.

A white wall in Parque Los Bebederos was one of Barragán’s famous screens for the play of shadows.

And closing off the space is an indigo wall. “It’s the perfect device to separate the park from the city,” Martín said. He’s a huge fan of Barragán — and now we are, too.

The blue wall in Plaza del Bebedero seen from another angle

The orange building is administrative and was where Barragán stored the supplies for the parties held in Parque Los Bebederos.

Wandering through Los Bebederos, which has changed so drastically since its heyday, I couldn’t help but wish we had been able to experience the Promenade of the Giants when it was a big deal — sipping a cocktail while cheering on the horses racing around the track. –Wally

Parque Los Bebederos (Los Bebederos Park)

Avenida Paseo de los Gigantes

Las Arboledas

52950 Cuidad López Mateos

México