From her role as queen to Thutmose II, God’s Wife, God’s Hand and queen regent to Thutmose III, here’s how Hatshepsut started her legendary career.

Hatshepsut isn’t a household name, but she should be! This wildly successful woman rose through the ranks of power in Ancient Egypt

It’s a shame more people don’t know about Hatshepsut, one of the greatest rulers of Ancient Egypt. She was born around 1500 BCE, a princess destined to marry the next pharaoh.

“Hatshepsut has the misfortune to be antiquity’s female leader who did everything right,” quips Kara Cooney in The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt.

“Every morning, Hatshepsut, as the God’s Hand, would rub the statue’s phallus until she felt it orgasm.”

Here are some fascinating facts I learned about this proto-feminist from Cooney’s book:

1. The role of the God’s Wife was one of the most powerful roles in Ancient Egypt.

As high priestess and “spouse” of the creator god Amun (aka Amen), Hatshepsut would have access to the most holy part of the Karnak Temple in Thebes (modern-day Luxor). Inside the sanctuary, where the god’s statue was kept, Hatshepsut would strip off her linen robe while the high priest offered milk (for Amun was reborn as an infant each day) and then bloody strips of meat as the deity grew in strength.

The chief god at the time, Amun, here seen merged with the one-armed, one-legged deity Min, needed to be given “a helping hand” every morning, and this was one of Hatshepsut’s duties

2. The high priestess was also the God’s Hand — meaning she had to jerk off the statue every morning.

God’s Hand, indeed! Hatshepsut was responsible for the rebirth of Amun each dawn. “Reverently, she took his phallus into her palm, allowing him to re-create himself through his own release,” Cooney writes.

While the sacred instrument called the sistrum rattled, the God’s Hand would rub the statue’s phallus until she felt it orgasm.

The Nile flooding, as seen in this photo from the 1890s

3. If the God’s Hand didn’t give a daily handjob to Amun, Ancient Egyptians believed the world would end.

What exactly did they think would happen? “The Nile would cease to flood its banks every year,” Cooney writes, “leaving no life-giving silt and mud in which to farm. The sun would fail to rise in the east every morning, depriving the crops of life-giving rays.”

Amun was often depicted as having the head of a ram

4. Hatshepsut might have been as young as 9 when she played the role of sexual consort to the god Amun.

While that makes us cringe in the modern day, Ancient Egyptians didn’t shield their children from sex.

“There were no religious strictures about the sinful nature of sex in the ancient world,” Cooney writes. “With no societal qualms about premarital sex or images of gods masturbating, and with many extended Egyptian families living in one-room homes with no protection of privacy, sex was simply more visible, even to a young child of the royal nursery.”

With the average person only living into their 30s, people started procreating once they hit puberty. “A short life expectancy meant that people grew up faster and started sexual activity younger than we would think appropriate or even ethical,” Cooney adds.

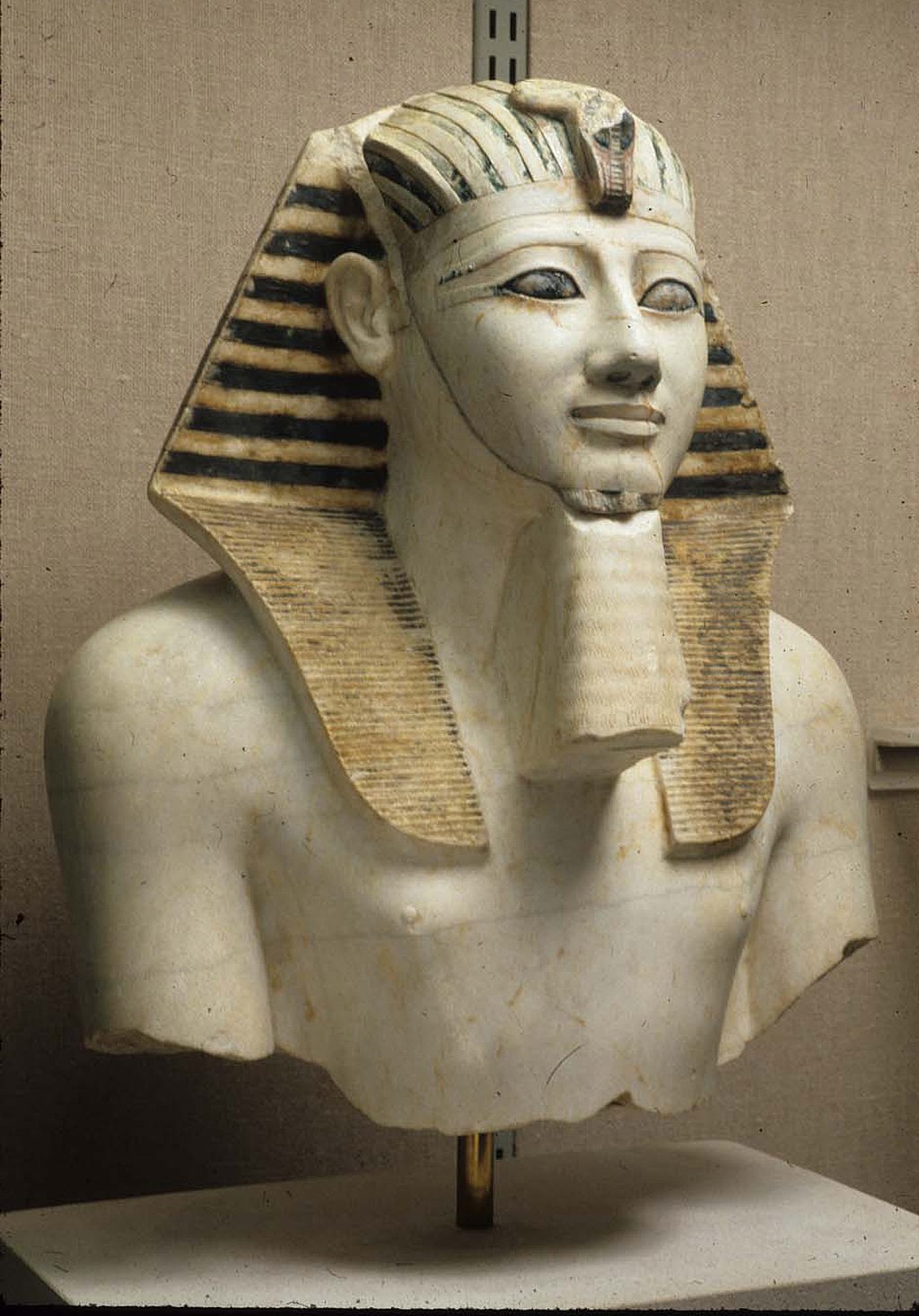

Thutmose II, Hatshepsut’s half-brother and husband, suffered from lesions, pustules and an enlarged heart

5. Hatshepsut married her younger brother, Thutmose II — incest was no big deal in Ancient Egypt.

In fact, the first gods themselves were pairs of brothers and sisters who procreated down the generations to Osiris and his sister Isis, who gave birth to Horus, embodied by the pharaoh.

And so, at the age of 12 or 13, Hatshepsut became the King’s Great Wife to her half-brother. By keeping it all in the family, fathers avoided having to pay dowries, they could keep a dynasty tightly knit, and the royal family would be emulating the very gods themselves.

6. Thutmose II was a sickly young man.

In fact, the king was a complete mess: “If the identification of the mummy of Thutmose II is to be believed,” Cooney writes, “the boy was never in good health. His skin was covered with lesions and raised pustules. He had an enlarged heart, which meant he probably suffered with arrhythmias and shortness of breath.”

Thutmose III was only a toddler when he became pharaoh, so Hatshepsut reigned as his regent

7. When a pharaoh died but his successor was too young, the queen stepped in as regent to rule until the king came of age.

In this case, Thutmose III, who was born of a secondary wife, Isis, was only 2 years old when his father passed away, a toddler drooling and pooping his days away in the royal palace. And so Hatshepsut, widow of the previous pharaoh, stepped into the power vacuum.

It might seem strange to give so much power to a woman in an ancient kingdom — especially given that Hatshepsut would have only been 16 after her husband’s short reign. But, as Cooney points out, “It was a wise and safe practice, as even the most narcissistic mother was unlikely to betray her own son, cause his murder, or otherwise conspire against him.”

The role of queen regent was enacted often during the Eighteenth Dynasty: “Young kings were so common during this time period that, according to the calculations of one Egyptologist, women had ruled Egypt informally and unrecognized for almost half of the seventy years before the reign of Thutmose III, an astounding feat given Egypt’s patriarchal systems of power,” Cooney writes.

8. There’s a good chance that Hatshepsut had numerous lovers, though she never again married.

We know not only how open Ancient Egyptians were when it came to sex but also how tied up sex was with their religion. So it’s fair to assume that Hatshepsut could and probably did find her pleasure wherever she desired.

“Given her position of power and her lack of a husband, she could have had relationships with any number of officials, young or old, male or female,” Cooney argues. “Why would we expect Hatshepsut to have embraced celibacy when she was the person to whom all looked for favor?”

A carving on an obelisk at Karnak shows Hatshepsut kneeling below the great god Amun

9. Within five years of her regency, Hatshepsut no longer held the position of God’s Wife.

We’re not sure why she gave up the position as high priestess (and lover of the great god Amun) or who succeeded her in the role — though it’s thought that she bequeathed it to her daughter, in the hopes that she would follow Hatshepsut’s ambitious career trajectory.

“Hatshepsut was in her early twenties,” Cooney says, “and strange as it may seem to us, she was probably too old to act as the sexual exciter of the god anymore.”

The loss of this powerful title could very well be what spurred the queen regent to grab more authority — and eventually become king. –Wally