Ever wondered why we carve pumpkins, dress up in costumes and go trick-or-treating? Learn the pagan origins of Samhain, when spirits roam the Earth and we can see into the future.

Halloween is the best time to cast divination spells

Halloween: You love it or you hate it.

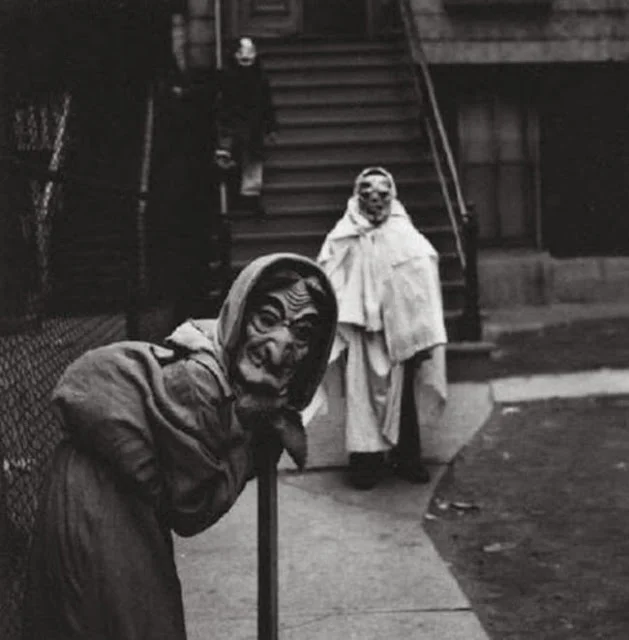

Our office manager dreads Halloween. She’s religious and sees it as an evil night, when devils and witches and demons and ghouls literally roam the streets.

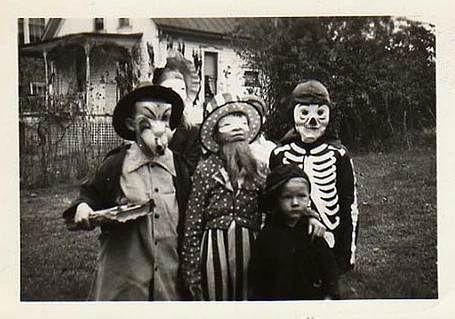

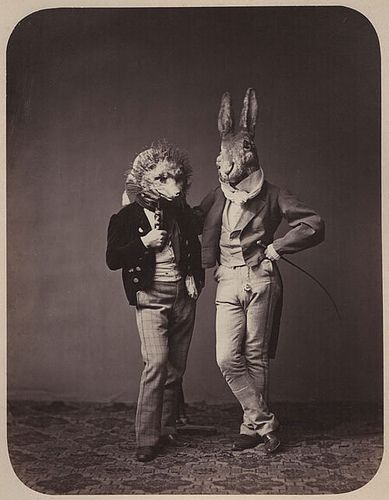

That, of course, is why many of us love it. It’s a chance to become someone else for a night. To embrace our dark (or sexy) sides.

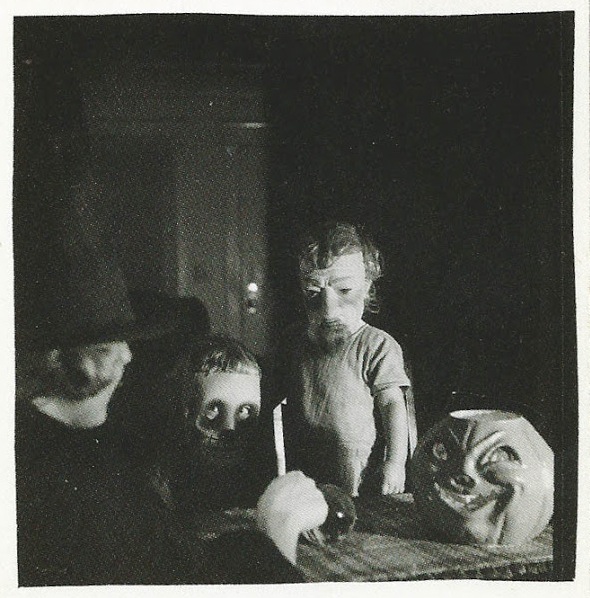

To the pre-Christian Celts of Western Europe, it was referred to as Samhain (actually pronounced “sow-en”) — a term still used by Wiccans. It’s the one day of the year when the veil between this world and the next is at its thinnest.

Halloween has its dark side — but it can also be a time of good luck

That means it’s the ideal opportunity to try to glimpse into the future. Divination spells work best on All Hallow’s E’en.

Young women would try to glimpse their future lover’s face in the mirror on Halloween night

Witchy Ways

If you want to get into the Samhain spirit, try these spells:

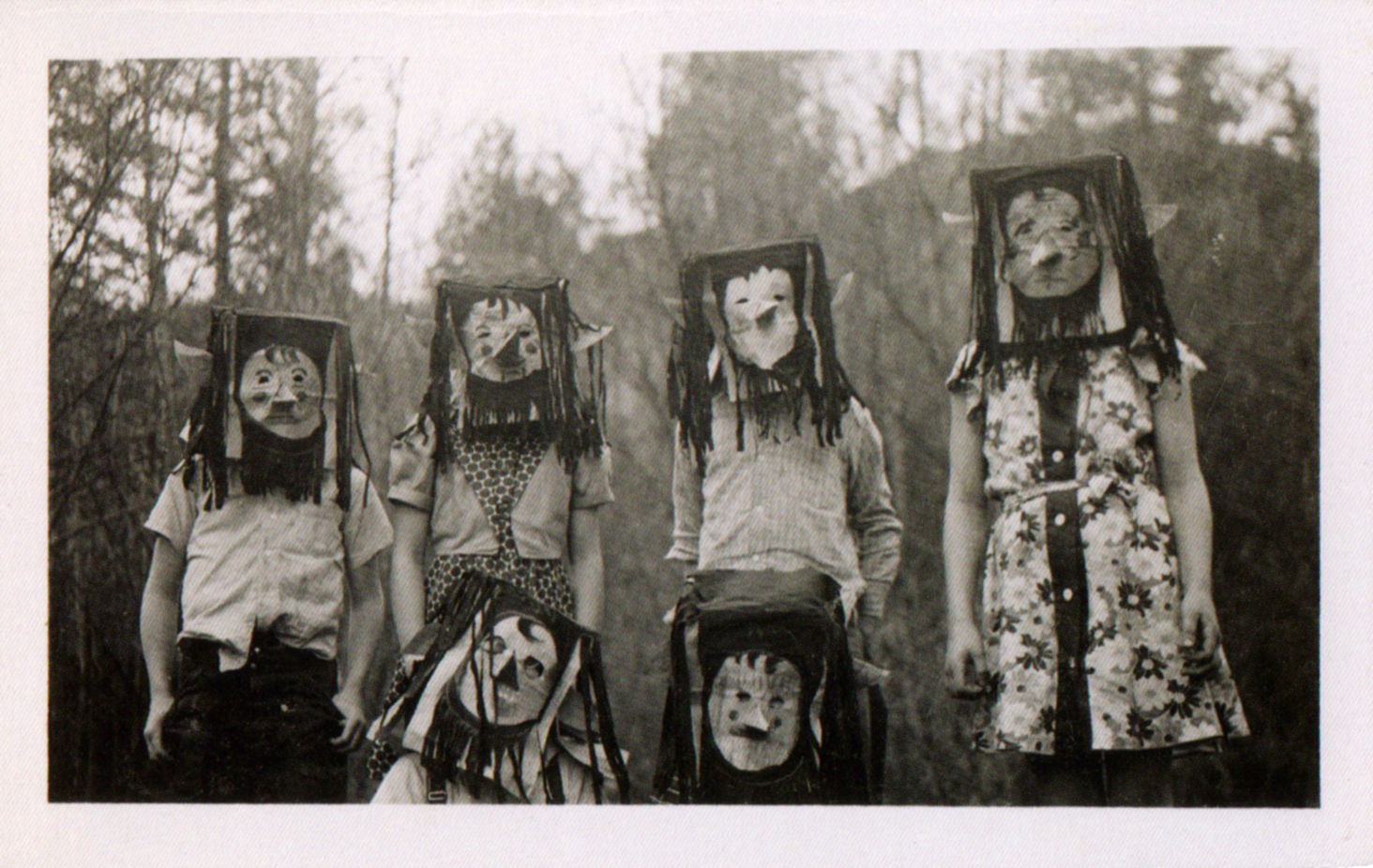

Witches, black cats and jack-o’-lanterns have become associated with Halloween

But it also means that ghosts and other unpleasant wraiths have the opportunity to invade the world of the living once darkness falls. People felt they had to protect themselves.

How did these origins lead to our traditions of carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns, dressing up in costumes and asking for candy with thinly veiled threats of mischief? What’s the history of Halloween, our strangest holiday?

Here’s an infographic I wrote (and the talented Kevin LeVick designed) for a website that’s sadly now defunct. –Wally