Why a riad is absolutely the best place to stay in Marrakech, with their interior courtyards with fountains and rooftop terraces. We chose one that’s a quick walk to Jemma el-Fna, the main square.

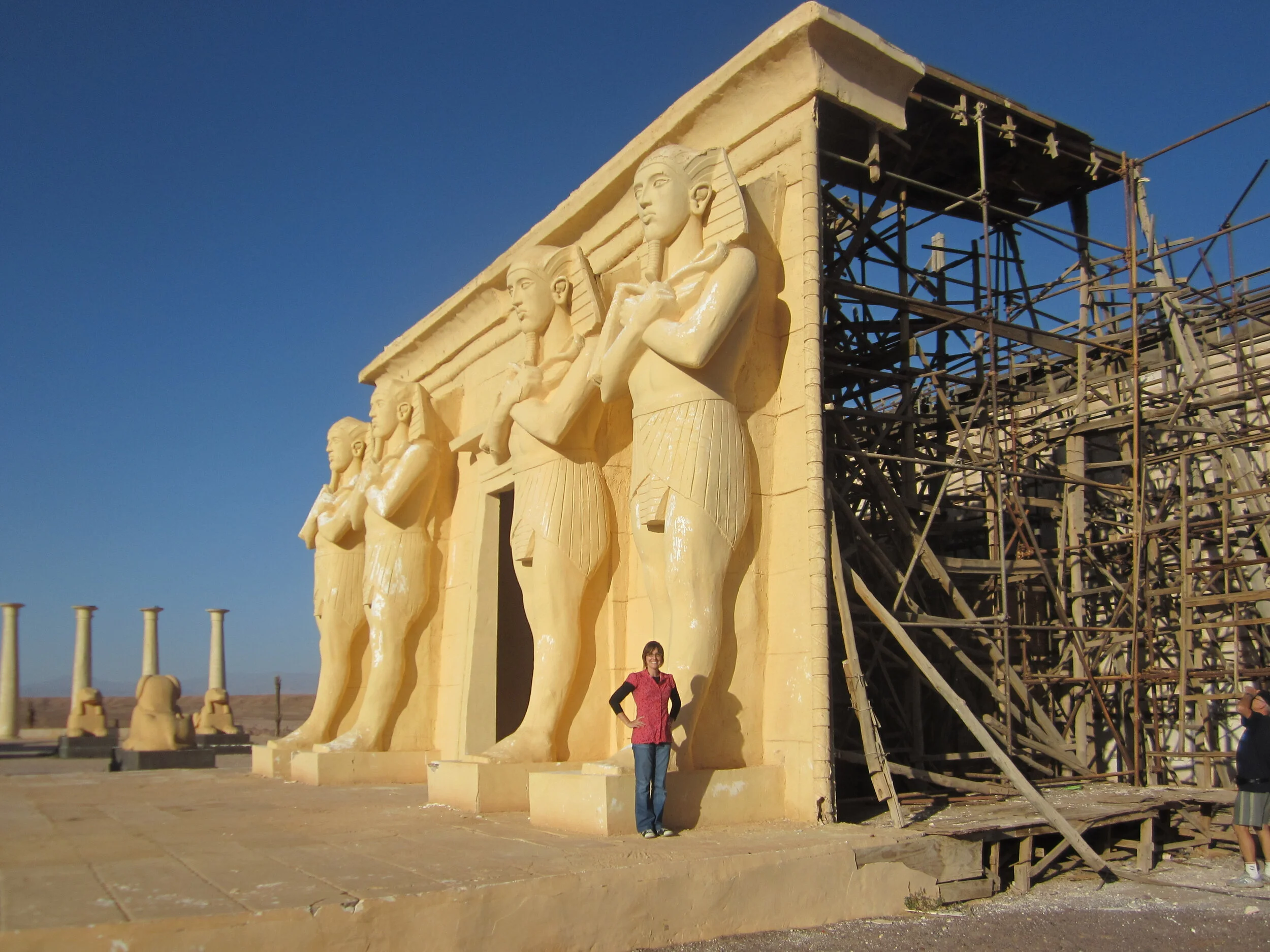

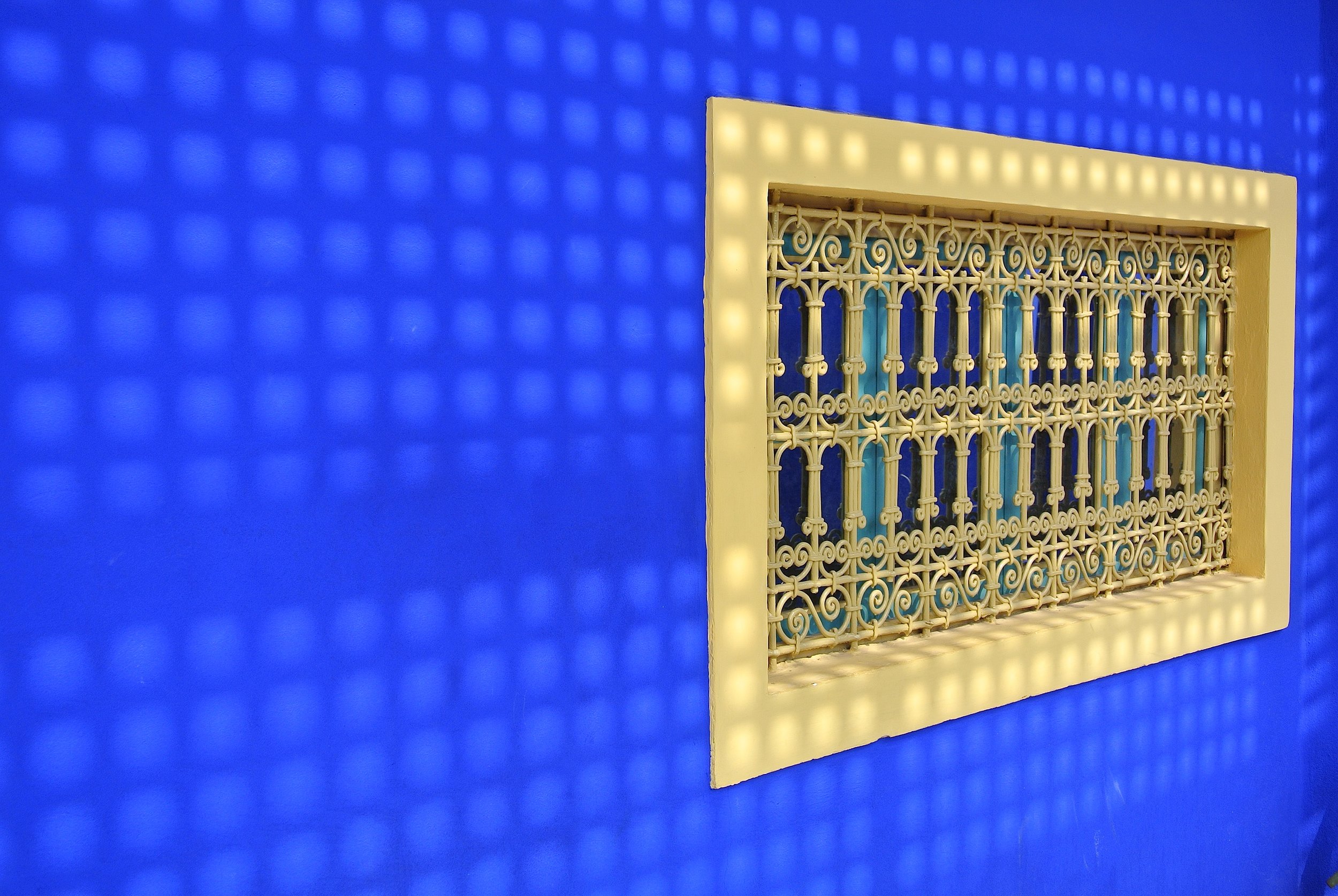

The interior courtyard of Riad Alwachma, Marrakech, Morocco

Part of the fun in planning a trip is figuring out where you’re going to stay. When Wally and I settled on Marrakech, I set to work to find a few options. The only criteria was to find lodging within the medina, the old quarter of the city surrounded by rammed earth walls.

I had narrowed it down to three riads and began showing them to Wally. He’d excitedly reply with, “Ooo, I like that one with the fountain in the middle!” To which I’d reply, “They all have fountains in the middle.”

Then he’d exclaim, “Ooo! I like that one with the rooftop terrace!” To which I’d reply, “They all have rooftop terraces.”

“OK,” Wally said, a huge smile on his face. “I get it.”

““Ooo, I like that one with the fountain in the middle!”

”They all have fountains in the middle.”

“Ooo! I like that one with the rooftop terrace!”

“They all have rooftop terraces.” ”

We settled upon Riad Alwachma, located a mere 10 minutes from the Jemaa el-Fnaa, the main square, and the souks.

Our driver, which we had arranged in advance, dropped Wally, Vanessa and I off at the entrance to Derb Bab Doukkala and led us with our luggage in tow down the cobbled road to the riad. Most derbs (often translated as alleys, but more like lanes) in the medina are too narrow for cars — not a bad thing as there are plenty of other types of traffic throughout, including mopeds and donkey carts.

We arrived at Riad Alwachma’s large wooden door and were cordially greeted by one of the proprietors, a charming French expat named Jérôme. The three of us passed through the threshold, and the quiet of the interior courtyard enveloped us.

Most riads have unassuming front doors, like that of Riad Alwachma — but such beauty lies within!

What’s a Riad?

Riads are the traditional former residences of wealthy merchants that have been converted into private guest lodgings. The term comes from the Arabic word ryad, meaning garden, and is applied to homes built around an inner courtyard or garden. They have unassuming façades that conceal a gorgeous interior.

Like all riads, ours had a large central courtyard that opened to the sky. In the center, a fountain laden with rose petals dancing on the surface gurgled faintly. A chirping bird was contentedly hopping along the floor.

Wally and I smiled conspiratorially at each other. Without missing a beat, Jérôme smiled too and told us that a bird in the house is a symbol of good luck.

A bird in the home is good luck, our host tells us — and a not-too-uncommon occurrence with the open-air central courtyard.

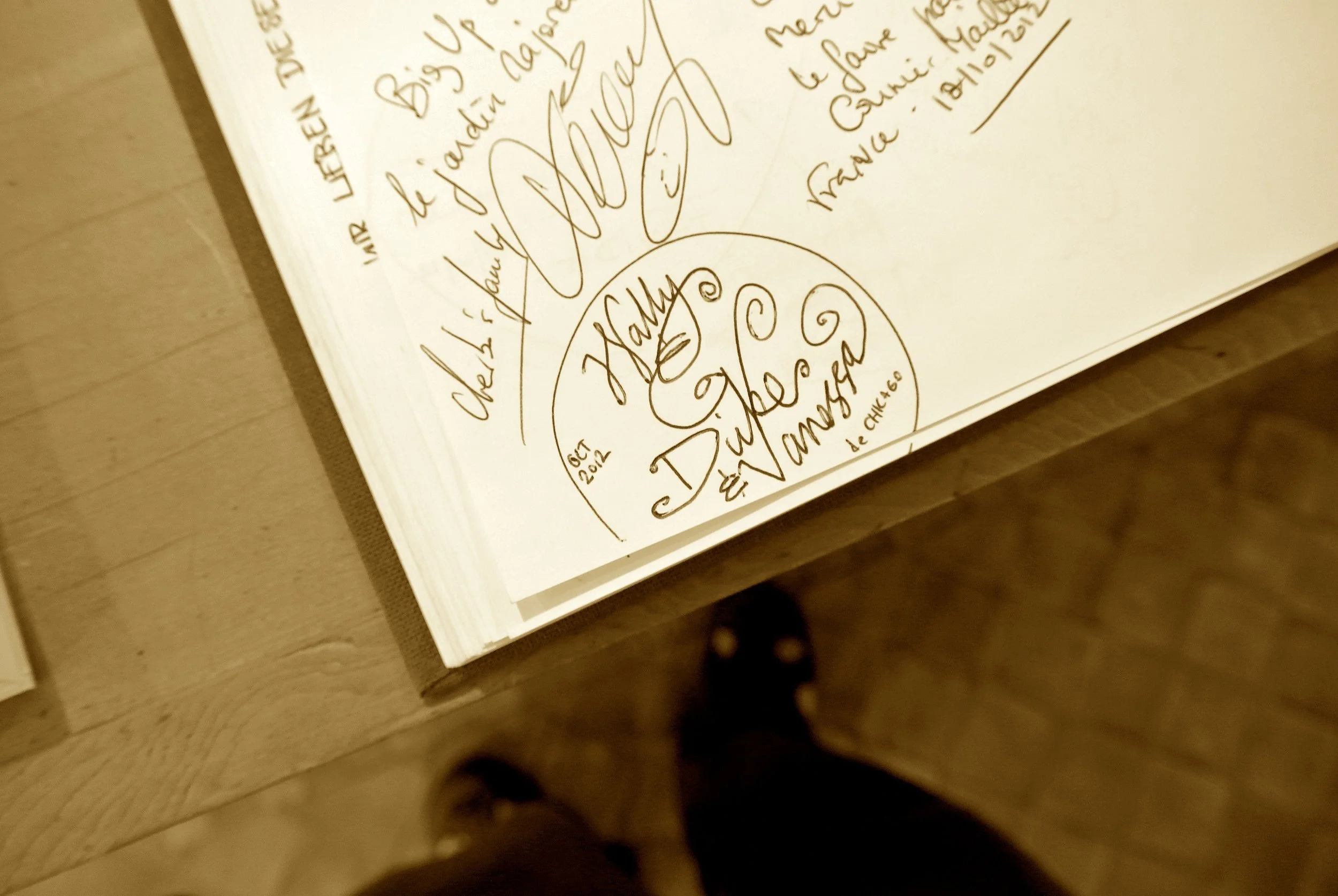

Vanessa, Wally and I sat at a table in the courtyard while Jérôme explained the origin of the riad's name. Alwachma comes from a traditional chin tattoo Berber women use to adorn themselves. I decided to nickname our riad The Girl With the Berber Tattoo.

Our host provided us with a map of the city and indicated points of interest and areas to avoid at night.

Getting Your Bearings in Marrakech

Over some pastries and our first cup of mint tea, which locals love to jokingly call “Berber whisky,” Jérôme explained that Marrakech tends to be a very safe city and that there are many uniformed police found throughout. But he did offer some advice on concealing our new camera because of the approach of Eid al-Adha, the Islamic festival to commemorate prophet Ibrahim’s obedience to Allah above all others. Jérôme explained that locals sacrifice animals on this feast day, and people occasionally do desperate things to provide their families with money to purchase a sheep or goat.

While we were more interested in the sights of the medina, from the Saadian Tombs to the El Badi Palace, Jérôme indicated Guéliz, the Ville Nouveau, or New Town, on the map. He kept saying that this was where we should go should we want to “make party,” an expression that made us giggle.

We finished our tea while mapping out our first of many adventures to come. First stop: Jemaa El-Fna and shopping in the souks, of course. –Duke

Riad Alwachma

27 Derb Sehb Bab Doukkala, Medina

4000 Marrakech

Morocco